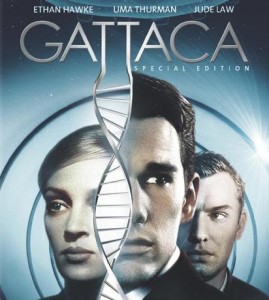

There’s a scene in the film Gattaca, which was written by New Zealand-born writer-director Andrew Niccol, that was going through my head during the discussions on pre-implantation genetic diagnosis that took place at Turnbull House in Wellington yesterday.

In the scene two brothers, Vincent and Anton, swim out to sea in a physical and emotional battle of wills. Only Vincent is weaker – he has a congenital heart defect that when he grows up will make him an outcast in society.

In the scene two brothers, Vincent and Anton, swim out to sea in a physical and emotional battle of wills. Only Vincent is weaker – he has a congenital heart defect that when he grows up will make him an outcast in society.

Despite that, it is Anton who tires and slips beneath the water, with Vincent coming to his rescue. When the two wash up on the beach, Antonio, the boys’ father is furious at Vincent, assuming it is he who was rescued and not the other way around.

As Vincent (now called Jerome and hiding under an assumed, genetically acceptable identity), later reflects:

“It confirmed everything in the minds of my parents – that they had taken the right course with my younger brother and the wrong course with me. It would have been so much easier for everyone if I had slipped away

that day. I decided to grant them that wish.”

What if Vincent had never even been born, if his parents had, as they did with Anton, chose to scrutinize his genetic make-up for abnormalities. Would the family be better off for it? Would society be better off for widespread use of such technology?

In few other areas of science are questions so fundamental to life thrown up. Which is why the Human Genomic Research Project is such an invaluable initiative and the work they have produced over the years, so well-respected.

But as you will discover if you listen to the podcast of Professor Mark Henaghan’s presentation to the symposium yesterday, the project’s leaders have never seen it as their responsibility to put the brakes on use of such technology because of the difficult ethical questions that are throw up. Indeed, some of the project’s findings in its third and final report, may come as a surprise.

For instance, the project suggests that insurance companies shouldn’t necessarily be regulated in their use of genetic information to screen potential customers.

“Many other countries have adopted legislative restrictions regarding the use of genetic information for insurance purposes. Such regulation should not be replicated in New Zealand,” the report finds.

The case against regulation comes down to “adverse selection”.

“Adverse selection occurs when individuals who know that they are high-risk procure insurance on a larger scale than if they were to pay a premium proportionate to the higher risk. This has obviously delterious effects as the cost incurred by the company increases premiums across the board. Consequently this may have a negative effect on lower-risk individuals who will purchase less insurance or none at all.”

In the US, the Genetic Information Non-discrimination Act, passed in May of last year, prohibits insurance companies from discriminating against customers based on genetic information. In the UK, there is a moratorium on insurance companies doing that in place until 2014.

Likewise, the report’s recommendation of extending the use of PGD embryo screening to test for conditions such as cancer and Alzheimer’s will raise eyebrows. Just read some of the comments at the bottom of this Dominion Post report on the subject.

Some will see this research as making recommendations that set us down a slippery slope. But Professor Henaghan doesn’t see it that way.

“Unless there’s clear evidence of harm… then you move ahead, don’t get in its way. That’s the way we’ve approached our research.”

The “its” he refers to is science and in the issues explored in this research, science largely equates with progress. Anyone considering having children who also has a serious hereditary disease in their family, will see the value of having genetic knowledge at embryo stage.

At the moment PGD use is very low, but what if a similar procedure becomes possible for natural pregnancy and in future, prospective parents are offered a cost effective genetic test that allows them to get a report card on their child’s future, long-term health prospects? Used on a large scale, how would this technology change the make-up of society? Would people act on that information leading to the mainstreaming of liberal eugenics, and a world like that portrayed in Gattaca?

It’s a scary concept, which is why there needs to be much more discussion of these issues before technology well and truly overtakes us and forces society to make a call on what we can and can’t do with such powerful information.