Increasing mobile phone use has led to public concern about possible cancer risks. The long-anticipated Interphone study is the largest, most comprehensive study on the risks to date, published today in the International Journal of Epidemiology.

The 10-year study is an interview-based, case-control study of mobile phone use in adults and focuses on the two main types of brain tumour, glioma and meningioma. It was coordinated by the WHO’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and carried out in 13 countries, including New Zealand.

Please see below for comments from New Zealand and Australian experts responding to the study’s findings.

In this SMC online briefing, a panel of New Zealand scientists — including contributors to the Interphone study — explain the latest results and their implications for public health and consumer safety.

Listen to an audio recording of the briefing:

Part I

[audio:https://www.sciencemediacentre.co.nz/wp-content/upload/2010/05/interphone-briefing-part-1.mp3]Part II

[audio:https://www.sciencemediacentre.co.nz/wp-content/upload/2010/05/Interphone-briefing-part-2.mp3]SPEAKERS

Prof Alistair Woodward – Head of School of Population Health, University of Auckland

Professor Alistair Woodward is Head of the School of Population Health at the University of Auckland, previously Professor of Public Health at the University of Otago Wellington. He is a medical graduate from the University of Adelaide, worked as an epidemiologist in Australia, Britain and New Zealand, and has interests in environmental health and tobacco control. He is a co-author of the NZ contribution to Interphone.

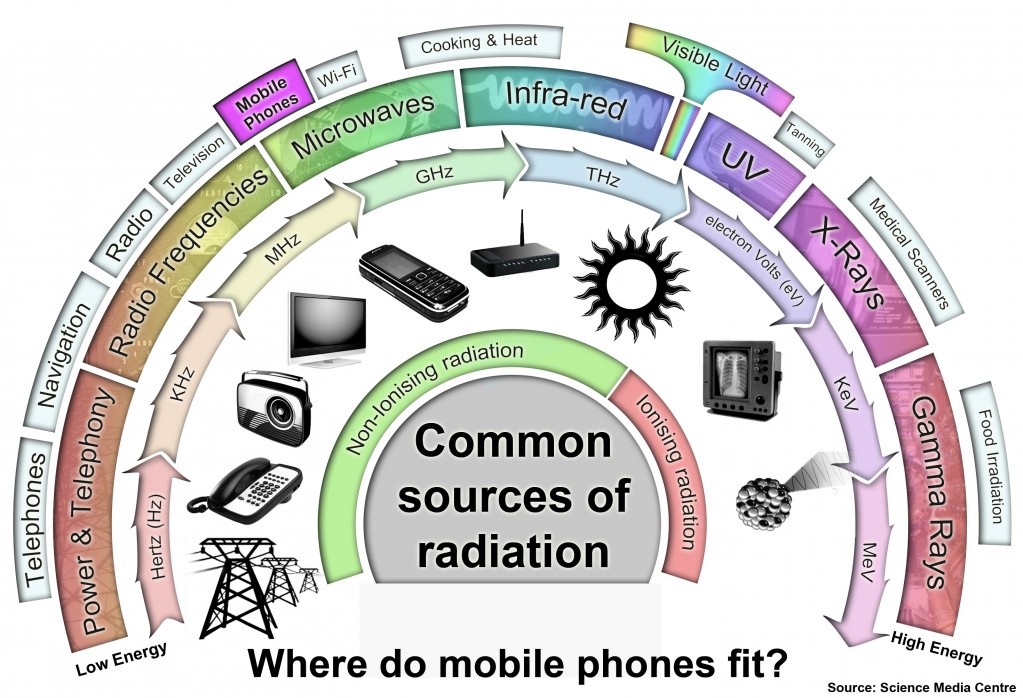

Dr David Black – Medical specialist

Dr David Black is an Honorary Senior Lecturer in Environmental Medicine at the University of Auckland, specialising in Electromagnetic Safety. He is a Vocationally registered medical specialist, a Fellow of the Australasian Faculty of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, a member of the Australasian Radiation Protection Society and a Member of the Royal Society of New Zealand. Dr Black, who was recently awarded the degree of Doctor of Medicine for his work in Standards rationale for mobile phone systems, is currently a Consulting Member of the International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection.

Prof Neil Pearce – Director of Centre for Public Health Research, Massey University

Professor Neil Pearce is currently Director of Massey’s Centre for Public Health Research, which conducts a wide range of public health research including respiratory disease, cancer, diabetes, Maori health, Pacific health and occupational and environmental health research. Professor Pearce has extensive research experience with a particular emphasis on public health and epidemiological methods. He is a co-author of the NZ contribution to Interphone.

Further comment on the study from New Zealand and Australian experts below:

Martin Gledhill, Senior Science Advisor at the National Radiation Laboratory comments:

- The full results are consistent with the findings that have already been published, so will not require a major rethink on how to handle the issue.

- Viewed together with laboratory data investigating the possible effects of radiofrequency fields (such as those from cellphones) on cancer, there is no persuasive evidence of a causal relationship.

- Nevertheless, given the high prevalence of phone use it is with pursuing further epidemiology studies now in progress to try and get more definitive answers.

- In the meantime, if people are concerned, there are simple steps (detailed below) which they can take to reduce exposures.

- So-called “3G” phones are now much more available than when the usage investigated in Interphone took place. These phones are very effective at reducing their output power to be just sufficient to maintain a call, so exposures from them are probably 20 – 50 times lower than those from the 2G phones which probably accounted for most of the Interphone usage.

“The full Interphone results for meningioma and glioma confirm the results already published from some of the components of the study, and recent reviews of these and other studies of brain tumours and cellphone use (eg the Ahlbohm et al review published in August 2009).

“Of course, the question to which we would all like a definitive answer is “Are cellphones safe?”. As an editorial in the Lancet pointed out a few years ago, this question is the scientist’s banana skin, and a Nobel prize awaits the person who designs an experiment to prove safety.

“While the full Interphone results overall do not suggest that cellphone use is associated with increased risks of brain tumours, the detailed analysis shows a small increased risk for the heaviest users (where use is quantified by hours, but not when it is quantified by the number of calls), but not for anyone else. The researchers caution against interpreting this as a cause and effect relationship as there is evidence that it could have arisen from biases in the data. The fact that laboratory research, including lifetime studies of animals, does not suggest that radiofrequency fields play a role in cancer development also weakens the likelihood that there is a causal relationship.

“Should individuals nevertheless be concerned about possible risks, there are simple steps they can take to minimise their exposures:

- Use the phone in places with a good signal strength, which allows the phone to transmit at reduced power. As discussed below, phones using the newer technologies (CDMA or 3G (UMTS)) provide even greater reductions in power.

- Limit the length of time spent on calls, and use a conventional phone if available.

- Use a hands-free kit, with the phone placed away from the body.

- Use a car kit with an external antenna. (Using a cellphone while driving, even with a hands free kit, is not recommended as studies have consistently demonstrated that this substantially increases the risk of accidents. Using a hand-held phone while driving is, of course, illegal.)

“Mobile phone technology and usage continues to evolve. In the time since most of the usage reported in the Interphone study took place, the so-called “3G” (third generation/UMTS) technologies have been widely introduced. Both 2G and 3G cellphones reduce their transmitting power automatically so as to be just sufficient to maintain the call. Studies have found that 3G phones are much more effective at this, and average transmission powers during a call can be 20 to 50 times lower than 2G phones, so exposures to the head will be correspondingly lower. (In fact the average output power of 3G phones is lower than cordless phone handsets as well. Even at their maximum output power, exposures from both 2G and 3G cellphones comply with the limits in New Zealand and international exposure Standards.)

“The Interphone authors acknowledge that further work is needed to try and resolve the question about potential risks for the highest category of users. This includes both further analysis using the Interphone data (looking at precise tumour locations), and new studies such as COSMOS which will follow up users and thereby be able to overcome some of the limitations inherent in any retrospective study such as Interphone.”

Our colleagues at the Australian SMC have rounded up the following additional comments:

Associate Professor Rodney Croft, Executive Director of the Australian Centre for Radio Frequency Bioeffects Research

“Until now it had been claimed that mobile phones were causing large scale increases in brain tumours. Because of its size, Interphone has provided the first study that has been both large and rigorous enough to address this claim. Interphone combined data from 13 countries on two types of brain tumour (meningioma and glioma), and compared mobile phone use in those who suffered from these tumours, to that of age- and gender-matched control participants. The rationale behind this approach is that if mobile phones were causing brain tumours, we would expect that those with more mobile phone use would have more brain tumours (and corresponding to this, those with more brain tumours would have used mobile phones more). Statistical analyses within the study thus looked for associations between brain tumours and mobile phone use.

“The Interphone results provide a clear indication that there is no association between mobile phone use and brain tumour rates (or at most, that if there was such an association it would be too small to be detectable by even a study of Interphone’s magnitude). Some spurious associations were reported, but as suggested by the authors, problems with them mean that they do not provide support for the claim that mobile phones cause brain tumours.”

Prof Bernard Stewart is Scientific Advisor to Cancer Council Australia

“The Interphone study has found no evidence that mobile phones cause brain cancer, consistent with previous research in this area. We already know that mobile phones are not able to damage genetic material (DNA) in cells directly and so cannot produce cancer-causing mutations. However, there have been concerns that electromagnetic fields from mobile phones may be able to increase the rate of cancer development by influencing cancer promotion or progression. The Interphone study has found no evidence supporting this theory. However, it did find that in patients with glioma, based on heavy phone use, the tumour was likely to be on the same side of the head as the mobile phone. While this does not prove a link between mobile phones and cancer, it does merit further research.

“Also, this study involves phone usage for 12 years at most and therefore tells us little about any risk associated with mobile phone use over decades. In particular, insufficient time has passed since mobile phones were introduced to determine whether or not there is a risk in children. Until there is research into this area, Cancer Council recommends caution in relation to children – they should not use, or minimise their use, of mobile phones. Anyone concerned about the harmful effects of electromagnetic energy should reduce their use of mobile phones, or employ hands-free technology.”