Hydraulic fracturing — a technology commonly known as “fraccing” or “fracking” — widely used in the oil and gas industry overseas has recently triggered some controversy in New Zealand, with critics raising questions over potential environmental impacts.

Hydraulic fracturing — a technology commonly known as “fraccing” or “fracking” — widely used in the oil and gas industry overseas has recently triggered some controversy in New Zealand, with critics raising questions over potential environmental impacts.

Though the technology has not long been used in New Zealand, it is expected to be a key part of some future coal seam gas extraction projects, as well as conventional oil and gas extraction.

The technology is already being widely used across the Tasman — where a similar environmental debate has been gathering momentum. The Science Media Centre has gathered comment on the issue from two Australian experts:

Dr Gavin Mudd, Lecturer in Environmental Engineering, Monash University comments:

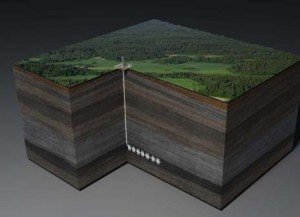

“Hydraulic fracturing (or ‘fraccing’) is used to create cracks, fractures and pathways in tight rocks and coal seams to allow water and/or gas to flow more rapidly out of the target layer. This helps economic gas extraction from a coal seam or oil shale and is a process widely used in the conventional oil and gas industry, to enhance flow and extraction rates.

“Fraccing has been around for decades in oil and gas industry, but only in the past two decades has it been applied to coal seam gas projects on an increasing scale. For coal seam gas projects, the long-term environmental impacts are very poorly studied and documented in the literature.

“The process does deserve significant environmental attention due to the potential severity of long-term groundwater impacts. Comparing the impacts entirely depends on what you compare it to — such as normal coal mining and energy production, conventional gas, baseload solar thermal or hydro-electricity.

“There is some research which sheds reasonable doubt on the purported lower greenhouse gas intensity of coal seam or shale gas due to large diffuse methane emissions. Given that the impacts are still poorly understood, it is difficult to make an accurate and fair comparison of the role of fraccing for gas.

“In the current public discussion, the impacts from chemical use are easily misrepresented, and are well worthy of some attention. The primary issues remain long-term groundwater impacts from coal seam or shale gas projects. More accurate data on groundwater impacts and especially greenhouse gas emissions is critically needed.

“At present, the industry is in media relations mode — and still fails to grasp the significance of the environmental risks and legitimate community concerns over these”.

Dr Rob Jeffrey, Research Programme Leader, Petroleum engineering CSIRO, comments:

“Fracturing started in the oil and gas industry in 1947 but was used in quarrying at least as early as 1900. Fracture stimulation of horizontal wells is approximately 20 years old and hydraulic fracturing has been used in coal seam methane since the 1970s.

“The main use of ‘fraccing’ is stimulation of onshore oil and gas wells in North America. As the better reservoirs are depleted, more stimulation will be required outside the US and Canada to produce from lower-permeability reservoirs.

“Some other applications can include measuring stress in the earth; disposal of both waste water and drill cuttings by re-injection into deep formations; collecting spilled hydrocarbons back into a central borehole, pre-conditioning ore or rock to allow it to cave in more completely, and increasing flows from water wells. Volcanic dykes and sills are examples of natural hydraulic fracture.

“Fracturing is being confused with drilling, which shows the level of understanding of some critics. Industry needs to maintain very high standards and government needs to be ahead of the crowd on regulation and enforcement.

“Gas from coal seam methane wells and shale gas wells will be a useful way of reducing CO2 emissions in the short to intermediate term as modern gas-fired electric generation emits much less CO2 per kWh than coal-fired plants.

“In the broader scheme of oil and gas exploration, much of the scrutiny is moving to drilling and casing as issues raised about hydraulic fracturing have been shown to not be that severe. Of course, regulations and standards have to be in place and enforced by regulators.”