With record inflation in New Zealand, growing unease about the price of milk and rising food costs globally, nutrition experts are increasingly concerned about the impact of food insecurity on the most vulnerable members of society.

Food insecurity is a lack of access to safe, nutritious and affordable food and according to research from the University of Otago, not only affects nutrition and physical health, but also the mental health of New Zealanders.

Food insecurity is a lack of access to safe, nutritious and affordable food and according to research from the University of Otago, not only affects nutrition and physical health, but also the mental health of New Zealanders.

The implications of food insecurity are potentially serious. For example, among children (who have high nutritional requirements), this could lead to impaired growth and development and increased risk of infections and diseases, say researchers.

The SMC rounded up comment from experts on the state of food security in New Zealand and some of the measures they claim would improve the level of food security in the country.

You can also listen back to a recent SMC media briefing on food insecurity featuring Professor John Coveney and nutritionist Clair Smith.

Dr Nikki Turner, Senior Lecturer in the Division of General Practice and Primary Health Care, University of Auckland and health spokesperson for the Child Poverty Action Group, comments:

“While there are a range of issues around food insecurity and families, the research bears out the clear fact that for most families inadequate income remains the central issue. It is too easy to blame it all on the parent and not recognise the environment these families are struggling in.

“Families with children are more likely to be in poverty than any other group in the New Zealand community, hence it is children who are more likely to suffer from poor nutrition, and currently, shamefully, one in five children live in poverty in our country.

“New Zealand research clearly shows that many families cannot afford to provide meals that meet national nutritional guidelines for their children; their budgets do not stretch far enough to provide diets that are nutritionally appropriate for children. Furthermore, since 2007 the cost of most food groups has risen substantially. Children get fed, they do not starve – but they do not get well fed.

“Nutrition has profound effect on the physical, mental and developmental outcome of the child: a poor diet affects a child’s immune system, making them more prone to infections and, paradoxically, obesity, and developmentally makes it harder to concentrate, focus and learn.

“All New Zealand children need access to healthy diets to give them optimal physical and developmental outcomes. There are many strategies New Zealand could be taking to focus on better nutrition for low income families: firstly, New Zealand needs to respond urgently to the needs of the 1 in 5 children who are noted by government statistics to be living in severe and significant hardship – these families need an adequate income for the children to have a reasonable start in life.

“The Child Poverty Action Group also recommends the need for a government commitment to funded breakfast programmes in low decile schools (decile 1 and 2). Our children should not be penalised for their inability to obtain a healthy diet.”

Vicki Robinson, public health dietitian and author of the recent report Food Costs for Families, comments:

“Food insecurity is a significant problem in New Zealand with results of the National Nutrition Survey, 1997 and the Ministry of Health National Children’s Nutrition Survey, 2002 revealing that 20-22% of New Zealanders experienced a lack of food security or food insecurity with much higher rates in Pacific and Maori people. These figures are now possibly even higher due to the current recession and increased unemployment levels, and the latest Ministry of Heath survey will be of interest to assess these impacts.

“Food insecurity is experienced more commonly in Maori and Pacific households with one third of Maori and one half of Pacific identifying with this issue. Higher prevalence also exists in females, younger age groups (25-44 years), those who have never been legally married or are separated, divorced or widowed. Sole parent families, large households, those unemployed or actively looking for work, those receiving a means tested government benefit, and those living in highly deprived areas are all more likely to be food insecure.

“Food insecurity has been associated with poorer nutritional and health status. Psychological stress has been found to be increased as have long term health outcomes such as obesity, diabetes and micronutrient deficiency.

“To solve the problem, a mix of interventions (taxation, subsidies and community action) are likely to be needed to effectively target those populations that are disproportionately affected by food insecurity. Strategies proposed include the removal of GST from fruit and vegetables, or the use of targeted electronic discount card (a modern food stamp), or vouchers and coupons available for low income groups to access healthy foods.

“Community driven strategies need to include the development of local markets, gardens and food cooperatives as a means of improving locally accessible and affordable foods.”

Dr Cliona Ni Mhurchu – Programme Leader in Nutrition & Physical Activity at the Clinical Trials Research Unit of the University of Auckland, comments:

“More than 60 years have passed since the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted stating that ‘Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and wellbeing of himself and of his family, including food’.

“Good nutrition is fundamental to health. While much focus is directed towards tackling problems of obesity and other diet-related non-communicable diseases, there remains a substantial number of people in New Zealand who do not have sufficient nutritious food to eat, and are classified as food insecure.

“The most recent national data (from 2002) showed that food insecurity was an issue for 20-22% of New Zealand households with children, with higher rates among Pacific peoples and Maori. Over half of Pacific and more than one-third of Maori households with children could not always afford to eat properly. Given the recent dramatic increases in food prices, it is highly likely that when the latest national nutrition survey (2008/09) report is released next month we will find that the number of households experiencing food insecurity in New Zealand has increased.

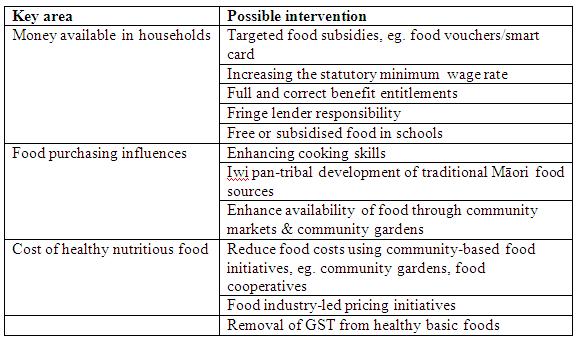

“Our research into ways to enhance food security suggests that key areas in which to intervene relate principally to availability of money within households; the cost of food; and food purchasing factors (the control parameters in the food security system). See below:

Delvina Gorton, National Nutrition Advisor at the New Zealand Heart Foundation comments:

“Kiwis are generally caring people who want everyone to have the basics they need to survive – like a roof over their head and food to eat. But as a nation we’re failing to keep up with modern realities. The last time it was checked (in the Children’s National Nutrition Survey in 2003), more than one in five New Zealand homes with children sometimes or often ran out of food due to lack of money. Everything would suggest that number is now likely to be worse.

“This issue is strongly related to income and wealth, but there are plenty of other factors involved. While food insecurity impacts most on low-income families, there are also people in the middle income bracket who are really struggling to feed their families. We’re all feeling the pinch of increased food and petrol prices – but when money is tight and you are only just scraping by, something has to give. For many families that means not having enough good quality food to eat, or not having any food at all.

“We have to think about what we value as a nation. My guess is that most Kiwis think having a fair shot at life, including kids not going to bed hungry, would be fundamental. In a country like New Zealand, where there is plenty of food to go round, it’s just not fair that lots of our kids and families aren’t able to get the healthy food they need, usually through no fault of their own.

“And of course food insecurity is associated with a less healthy diet and micronutrient deficiencies, higher rates of disease, stress and depression, poor academic development, and behavioural and psychosocial issues in kids – so it has major implications.

“There’s no quick fix. There are lots of things that can help, such as fruit in schools, school breakfasts, community gardens, or community fruit and vegetable markets. But to really fix the problem we have to help people increase their income and the money they have for food as well as make healthy food more affordable. This requires cooperation between government departments, industry and communities to work together on issues like employment, subsidies or tax credits, housing, education, health, and the price of food. An example of one promising strategy is an electronic discount card that could be targeted to healthy food for hard-up families.”