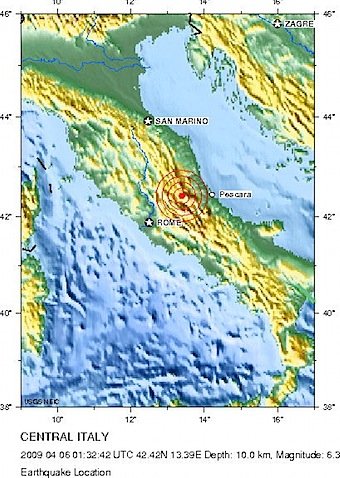

Several Italian earthquake scientists are currently standing trial for manslaughter, after accusations that their lack of warnings led to the deaths of hundreds when a 6.3 magnitude quake struck the city of l’Aquila in 2009.

New Zealand’s research community has spoken out in defence of the scientists, with several high profile geologists publicly backing the accused. The first day of the trial just finished this morning (NZT).

New Zealand’s research community has spoken out in defence of the scientists, with several high profile geologists publicly backing the accused. The first day of the trial just finished this morning (NZT).

Prior to the earthquake in L’Aquila, Italy, scientists and officials on the nation’s major risks committee allegedly played down the risk of a possible quake in the area, based on a the patterns of small tremors occurring. A week later the city was hit by a 6.3 quake which lead to widespread collapse of buildings and resulted in 309 deaths.

The Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera reported the L’Aquila Judge Giuseppe Romano Gargarella said that the seven defendants had supplied “imprecise, incomplete and contradictory information,” in a press conference following a meeting held by the committee 6 days before the quake. In doing so, they “thwarted the activities designed to protect the public,” the judge said.

You can read more detailed reporting of the trial below.

Nature News: Scientists on trial: At fault?

BBC News: Italy scientists face trial over L’Aquila earthquake

Following the announcement of the trial in May, Italy’s National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology (INGV) published a letter of support for the scientists, which has been signed by over 5000 researchers world wide, including 81 New Zealanders.

The final paragraph of the letter states:

“The scientific community involved in earthquake science urges the Italian government, local authorities and decision makers in general, to be proactive in establishing and carrying out local and national programs to support earthquake preparedness and risk mitigation rather than prosecuting scientists for failing to do something they cannot do yet – predict earthquakes.”

The Science Media Centre contacted some the the New Zealand signatories and earthquake experts for further comment on the trial of the scientists.

The comments below reflect the views of the researchers and do not necessarily represent the opinions of their employers.

Dr Mark Quigley, Senior Lecturer in Active Tectonics and Geomorphology, University of Canterbury, said:

“Italian seismologists are being prosecuted for failing to provide sufficient warning of the risk of a major earthquake prior to the 2009 L’Aquila Mw 5.9 event. Specifically, the prosecution claims that scientists provided authorities and the public with “generic, ineffective, incomplete, imprecise, and contradictory information about the nature, causes, and future developments of the seismic hazards in question”. This was compounded by the fact that the mainshock followed 3 months of smaller earthquakes that were reclassified as ‘foreshocks’ following the Mw 5.9 event.

“A survey of major earthquakes in Italy spanning the last 60 years indicates that only 6 of 26 have been preceded by foreshocks and that many swarms have occurred without subsequent large earthquakes. As foreshocks do not appear to have any different characteristics from isolated ‘background’ earthquakes characteristic of regional seismicity, they cannot be used as diagnostic precursors to major quakes (Note that the 2011 Mw 9.0 Tohoku (Japan) earthquake was similarly preceded by foreshocks, the largest being a Mw 7.2 earthquake two days prior to the 9.0 event). So while one could say that the chance of a major earthquake might increase during a seismic swarm, history dictates that most major earthquakes do not have precursor foreshocks and swarms do not always lead to large earthquakes, such that the probability of delivering a ‘false alarm’ and causing undue panic would have been quite high.

“To me this highlights the importance of effective science communication; it is important to provide the public with probabilistic earthquake ‘forecasts’ but it is equally important to contextualize these assessments (e.g., earthquake probabilities in the midst of an aftershock sequence compared to ‘background’ probabilities) and to provide sufficient information on the methodology and limitations of these forecasts.

“And finally, it is important to emphasize to the public that no precursory phenomena (e.g., gas release, micro-earthquakes, thermal anomalies, animal behavior, strain rate changes, electrical phenomena, lunar phenomena) have produced a successful and reproducible short-term earthquake prediction scheme. This is not for lack of trying, and these methods should continue to undergo scientific testing and scrutiny. However, the holy grail of earthquake prediction, as defined through specification of a defined geographic region, depth, time window, and magnitude range, remains elusive at present.

Dr David Rhoades, Principal Scientist & Geophysical Statistician, GNS Science, said:

“I signed the letter because I felt strongly that it is unjust to prosecute scientists for failing to predict an event that was unpredictable by any scientific method. In my opinion, the most scientists can do is to estimate the probability of an earthquake occurring in a given space-time-magnitude window. Giving any kind of warning, or advice to the public of what to do in the light of such information, is the proper responsibility of government authorities, and not of their scientific advisors.”

Prof Martha Savage, Professor of Geophysics, Victoria University of Wellington, said:

“I think that the incident shows that there is a big gap between what scientists can deliver and what the local population and politicians want us to be able to deliver. It is also not helped by non-scientists who claim to “predict” earthquakes. It is quite difficult to know what to tell people when there is an earthquake.

“My own research has shown that in general in New Zealand, when a moderate earthquake occurs (that is not already part of an aftershock sequence), there is about a one-in-twenty possibility that another one of the same size or larger will happen within the next few days. That possibility gets lower quickly and the likelihood of big earthquakes is still small (less than 1 in 100 that an earthquake a whole magnitude larger will happen in that same time period). Yet the possibility of a big earthquake is quite a lot (100s to 1000 times higher depending on how you count it) than it was just before the earthquake.

“I usually try to communicate this to people who are concerned, and I also tell them that they should use such earthquakes as warnings to check their earthquake supplies and be sure their house is earthquake-proof. When I present the statistics as one in 20 chance of a bigger earthquake, people usually think that a one-in-twenty chance is small, and they stop worrying. But if I tell them the chance has increased more than 100 times, they will worry. Thus I can report the same information in a way that can worry or reassure people.

“I had a few people tell me after the September Darfield earthquake that I should have given people more reassurance-that they didn’t want to hear about further risks, they wanted to feel safe. Certainly after the February earthquakes I was happy that I didn’t respond to that pressure.

“Apparently one of the non-scientists attending the meeting in L’Aquila Italy falsely stated to the population that moderate earthquakes decrease the risk of big events. I think he was responding to similar pressures. And 99 times out of 100, no large earthquake would follow the small ones. I think that he was incorrect but he may also have believed it himself-people want to believe that things will get better. So he was wrong, but I don’t think that his behaviour was criminal in any sense of the word.

“There have in fact been a couple of studies of the L’Aquila earthquake that suggest that the large foreshock may in fact have changed the fluid pressure just before the mainshock and perhaps if similar studies could be done in enough other earthquake sequences one might be able to use such studies to help to decide which future earthquakes can be triggers for larger ones. But such work is only in its infancy.”

To what degree should scientists be held accountable for their announcements regarding natural hazard risks?

“If the public decides to make scientists accountable through fines or jail terms for their announcements regarding natural hazard risks, the scientists will respond by not saying anything, and possibly by moving their research into areas where they are not as likely to encounter such uncertainty. Therefore, the public will lose out. ”

Have the Canterbury earthquakes changed the way the public view scientific information regarding risk?

“I still find people telling me that their friends are very worried every time Ken Ring makes a prediction, even though all scientists I know of discount his views.

“I think the insurance companies are rightly judging that there is still a risk of earthquakes in the region. Their money is at stake and they are likely to err on the side of caution.

“GNS Science is in my opinion doing state of the art work to assess the current probabilities of new earthquakes in the region and yet nobody can predict exact times and magnitudes.”

Prof Euan G C Smith, Professor of Geophysics, Victoria University of Wellington said:

“It appears that the indicted scientists are being blamed for the lack of preparation by the community for the event that happened. That is unjust.

“In 1987 I was involved in a situation with some similarities.

“In February 1987 I was acting superintendent of the Seismological Observatory, DSIR, when an earthquake swarm started (Feb 21) near Maketu in the central Bay of Plenty. After a few days of activity, my Director thought we should say something about the earthquakes. Accordingly I issued a press statement on March 2 saying that there was no reason to expect that the earthquakes would lead to a bigger one (such swarms are common there) BUT that earthquakes were likely to be ongoing and residents should take sensible precautions.

“While this was being aired by the media, the Edgecumbe earthquake (mag 6.5) struck at 1.42 pm. I was somewhat derided in the media – the Auckland Star sent me an electric kettle for getting into hot water. It might have been much worse for me if there had been heavy casualties, but there weren’t. Of course, no-one wanted to read the disclaimer (‘BUT…’) And so the main lesson that I took from these events is that extreme caution is required in such circumstances. I thought I had covered off the possibility of something larger happening, but the media didn’t.

“In similar circumstances I would make a statement again, albeit with the benefits of this (and other) experience. The public are entitled to expect that experts will give them an opinion. If we (scientists) have not adequately explained that the future is uncertain and that, in particular, earthquakes cannot be predicted deterministically, then that’s our fault.

To what degree should scientists be held accountable for their announcements regarding natural hazard risks?

“I was accountable for the statement I made at the time, and would expect to be in future. I note that Mr Ring is not accountable for his statements.”

Have the Canterbury earthquakes changed the way the public view scientific information regarding risk?

- Many more people in New Zealand now understand that earthquakes can only be ‘predicted’ probabilisitically.

- At least one centre – Wellington- has been galvanised into action over its stock of earthquake prone buildings, and there appears to be widespread acceptance, in Wellington at least, that civic preparation against earthquakes is essential even if it means some loss of ‘heritage’.”

Our colleagues at the Australian Science Media Centre also collected the following commentary:

Prof Paul Somerville, Deputy Director, Risk Frontiers, Macquarie University, said:

“On April 6, 2009, a magnitude 6.3 earthquake killed 308 people in the Italian city of L’Aquila, following an earthquake swarm that had produced felt earthquakes daily for four months. The case against the scientists was initially understood as relating to their failure to predict the earthquake (an error of omission), but is now focused on their having provided “incomplete, imprecise and contradictory information” about earthquake risk (an error of commission).

“Specifically, the local government’s prosecution argument is that the reassuring information the scientists provided at a meeting held one week before the earthquake, to the effect that a major earthquake was not imminent, inhibited the citizens from taking precautions that would have saved lives, especially as two large foreshocks occurred the day before the early morning mainshock.

“It appears that the government’s objective in holding the meeting was to debunk unreliable but alarming earthquake predictions that were being made by L’Aquila resident Giampaolo Giuliani, who is not a seismologist, and that the scientists were distracted in this direction instead of focusing on information about earthquake risk that the citizens needed. Further, it appears that the scientists found themselves answering questions about deterministic prediction of earthquakes (which they acknowledge is not currently possible) instead of probabilistic forecasting of earthquakes (which they can do).

“However, probabilistic forecasting has very low absolute probabilities, even when the increase in probability is high. For example, Italian seismologists estimated that the probability of a large earthquake in the next three days increased from 1 in 200,000 before the earthquake swarm began to 1 in 1,000 following the two large foreshocks of L’Aquila earthquake.

“Such low probabilities make it difficult for scientists to place a large degree of importance on their forecasts. Scientific errors made by members of the Commission exacerbated the situation. Dr De Bernardinis, who is an expert in floods, not earthquakes, incorrectly stated that the numerous earthquakes of the swarm were releasing stress and thereby inhibiting the occurrence of a larger earthquake. Dr Calvi, who is a structural engineer, misunderstood the seismologists as thinking that the earthquake swarm had no impact on the likelihood of a larger earthquake; in fact the probability was estimated by the scientists to be several hundred times higher, as we have seen.

“Ironically, the prosecution of the scientists, especially if it is successful, is likely to imperil the very need that this incident has highlighted: for open and clear communication between the scientists and the public. In a further irony, no action has yet been taken against the engineers who designed modern buildings that collapsed and caused fatalities, or the government officials who were responsible for enforcing building code compliance. It has occurred to some observers that the local government officials may be scapegoating the scientists to avoid prosecution themselves. ”

This summary builds on excellent articles in Nature Vol. 477 p. 265, 15 September 2011 and The Economist, 17-23 September 2011 p. 86-87.