IBM today released its second Innovation Index revealing that New Zealand’s overall innovation rate increased three per cent in the four years to 2011, boosted by increased spending on research and Development during the global financial crisis.

R&D expenditure grew at an average rate of 7.6 per cent per annum between 2007 and 2011, largely driven by the public sector, but growth slowed to 3.7 per cent in 2011 – 2012 as the economy started to recover. The equivalent of 4600 full-time R&D jobs were created during this period. However, when the economy started to recover during 2011-12, the growth in R&D expenditure slowed to an average of 3.7 per cent per annum.

R&D expenditure grew at an average rate of 7.6 per cent per annum between 2007 and 2011, largely driven by the public sector, but growth slowed to 3.7 per cent in 2011 – 2012 as the economy started to recover. The equivalent of 4600 full-time R&D jobs were created during this period. However, when the economy started to recover during 2011-12, the growth in R&D expenditure slowed to an average of 3.7 per cent per annum.

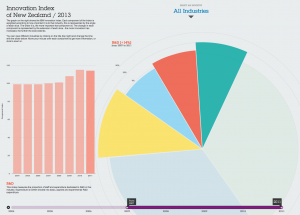

An interactive graphic displays the data used in the Innovation Index breaking down innovation by sector and type of activity.

Some highlights from the second IBM Innovation Index (the first was undertaken in 2010):

– R&D created the equivalent of 4600 full-time jobs between 2007-10, when the equivalent of 12,600 full-time jobs were lost across the economy as a whole.

– By 2012, nearly 50,000 New Zealanders were employed to conduct R&D, 35,000 in research roles and the remainder in support roles.

– Applied R&D expenditure grew by 46% between 2008-12; much faster than either Experimental R&D (14% growth) or Basic R&D (3.4% growth).

– Intellectual Property (IP)- trademarks, patents, Plant Variety Rights and designs- registrations per business in each industry fell 5% between 2007 and 2011.

Professor Shaun Hendy, Victoria University innovation expert, in a commentary piece on the research said:

In a market economy, innovation policy should maximise economic rather than market value. While an improvement in on-farm productivity may generate a large market return, the economic value of such an improvement may not greatly exceed this. In contrast, the economic value of an innovation that leads to the establishment of a new technology company and seeds a new industry sector may substantially exceed its market value. The difficulty, of course, lies in the ability of policy to identify economic benefits in excess of market value.

Specialised economies are vulnerable to macroeconomic volatility, and those that specialise in agriculture are especially exposed to climate change and biosecurity threats. New Zealand’s long-term future will depend on its ability to exploit economic opportunities outside its traditional primary sector strengths. To create such opportunities and to maximise the economic value of its investments in innovation, New Zealand will need to diversify its research and development portfolio.

Chief Science Advisor to the Prime Minister, Professor Sir Peter Gluckman said:

Technology transfer from the public to private sector is often seen as the issue, but this may be an over-simplification. The issue appears to be more about the need to increase the flow of ideas and to have appropriate vehicles to take those ideas to commercial scale rapidly, rather than any cultural resistance to that transfer. Certainly, we need to improve the knowledge that both the academic community and the private sector have of each other. Developments such as Callaghan Innovation are part of a robust pathway to change that is reflected in the growing research intensity of our private sector.

However, there remain real limitations in our access to risk capital, to expertise in technological global marketing and in company expansion. Our private sector is dominated by small and medium sized organisations and, relative to other small countries, they are indeed vibrant and research-intensive. The problem is that our ecosystem lacks research-intensive global corporations, which in other countries, both large and small, not only are large research consumers and providers but also offer very important spill-over effects for the whole innovation ecosystem. The lack of such corporations within the New Zealand ecosystem is a major constraint.

IBM New Zealand’s chief technologist, Dougal Watt, said:

When IBM expanded its research activities after the Second World War, our focus was on fundamental scientific research, where effort was guided by interest in the problem and not by external considerations. This model worked well for many years but eventually proved inadequate, in part because research conducted

in isolation from the needs of clients could not, on its own, drive the sort of innovation that creates new markets and new opportunities. The other flaw in this model was that it did not clearly link our research efforts with IBM’s strategic business direction. We did not use our researchers’ knowledge of the future to help us make important decisions about how to evolve and adapt IBM’s business model to keep pace with changes in technology and business.

So IBM changed its innovation model to ensure our researchers were more closely connected with the needs of our clients and the marketplace, and to ensure that our researchers had direct input into decisions about IBM’s strategic direction

These changes have allowed us to more effectively commercialise our research efforts and open up new markets. They have also helped us forge deep, highly collaborative relationships with our clients – relationships that have delivered better research outcomes. The success of this model can be seen in IBM’s continued leadership in U.S. patents: 2012 marked the 20th consecutive year that IBM topped the annual list of U.S. patent recipients, with a record 6,478 patents granted, more than to any other research organisation.