Destruction of the planet’s protective ozone layer is slowing, according to the latest scientific assessment, but full impacts on global climate are still coming clear.

The first comprehensive update on global ozone in four years has been released today from the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) and the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO). The Assessment for Decision-Makers, a summary document of the Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion 2014, is the work of a panel of 300 scientists, including three New Zealanders.

The report analyses the impact on the ozone layer of concerted international action since the adoption of the Montreal Protocol in 1987. It also assesses the implications of the phase-out of ozone-depleting substances on efforts to address climate change.

Key findings include:

- Total ozone has remained relatively unchanged since 2000, though there is a clear recent increase in ozone in the upper atmosphere.

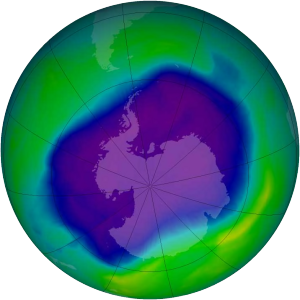

- An ozone hole continues to form over the Antarctic each year in spring.

- Ozone loss has caused significant changes in temperature and rainfall during Southern hemisphere summers over the past thirty years.

- Coolants used to replace ozone-depleting CFCs are a rapidly growing source of greenhouse gases, raising concerns that climate gains from the phase-out may be undermined.

The full report can be downloaded from the UNEP and WMO websites

A press release is also available from NIWA with comments from report reviewer Dr Olaf Morgenstern.

The Science Media Centre rounded up the following expert commentary. Feel free to use these quotes in your reporting. If you would like assistance reaching these or other experts for follow up, please contact the SMC.

Prof Martin Manning, Climate Change Research Institute, Victoria University of Wellington, and reviewer of the report, comments:

“The 2014 Ozone Assessment has now put more emphasis on providing a summary of the science relevant for policymakers. This is important because success of the Montreal Protocol for managing ozone depleting gases now sets a precedent for control of greenhouse gases and their effects on global climate.

“Ozone levels have stopped decreasing in the stratosphere and there is evidence for increases in some places, but still a range of different estimates for the overall recovery rate. Significant year to year variability in the size of the Antarctic Ozone hole also means that some uncertainties will probably remain for several years. Furthermore, a very large loss of ozone occurred over the Arctic in 2011 and was not predicted. However, it now appears that while this type of extreme event may reoccur, it is not part of a long term trend.

“This report is showing very clearly that ozone depletion has had a significant effect on climate in the southern hemisphere over the last thirty years because of its effects on atmospheric circulation patterns which affect temperature and rainfall. Such links between ozone depletion and climate change work in both directions and, as CO2 and the other greenhouse gases increase, changes in circulation will decrease future ozone levels in the tropics.

“Because the CFCs and HCFCs are very strong greenhouse gases, rapid moves away from their use has reduced human forcing of the climate system by much more than the Kyoto Protocol. But their replacement with HFCs, which are potent greenhouse gases in their own right and are now increasing rapidly, means that these will become an increasing cause of climate change during this century.

“New chemical compounds are now being developed that may start to replace the HFCs, but this shows that some forms of continuing technological development are going to become an important factor for maintaining the environment that we depend on.”

Dr Joseph Lane, Senior Lecturer in Physical and Theoretical Chemistry, University of Waikato, comments:

“The latest report by the United Nations World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) provides an update on how Earth’s ozone layer is recovering since restrictions were placed on the usage of molecules that destroy ozone when released into the atmosphere.

“Ozone makes up a very small part of our atmosphere, but its presence is vital to human well being. Most ozone can be found high up in the atmosphere, between 10 and 40 km above Earth’s surface in what is commonly known as the ‘ozone layer’. This ozone layer absorbs most of the harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the Sun that among other things can cause sunburn and skin cancers.

“The 1987 Montreal Protocol first restricted the use of some ozone depleting molecules such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), which were commonly used in refrigeration systems and as propellants in aerosol cans. However, because these molecules are generally long-lived, we are only now starting to observe signs of the ozone layer recovering.

“It’s fantastic to see a global initiative like the Montreal Protocol actually making an effect and gives hope that a serious commitment to global Climate Change policy can also be successful. The report predicts that the ozone layer in the Southern Hemisphere will return to normal levels by 2030-2040.

“As the use of CFCs decline, one of the main uncertainties in the recovery of the ozone layer is the effect of nitrous oxide emissions. Nitrous oxide is best known as a potent greenhouse gas but it is also a significant ozone depleting molecule. Bacterial processes in soils that are nitrogen-rich are the primary source of nitrous oxide. This makes managing nitrous oxide emissions particularly problematic for a country like New Zealand where agricultural practices are expanding and becoming more intensified.”

Declared interest: I am Principal Investigator on a research project funded by the Royal Society of New Zealand Marsden Fund, “Photodissociation of nitrous oxide”.