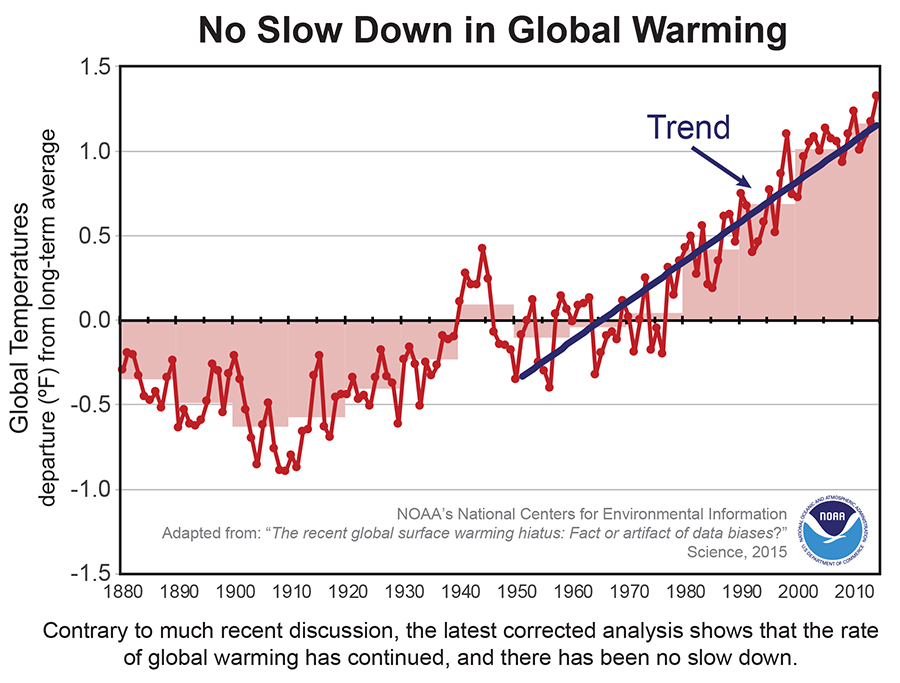

The widely reported slowdown of global warming since the start of the millennium – often called the ‘hiatus’ – is in fact a result of bad data, according to new research.

The new study from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, published today in Science, presents an updated global surface temperature analysis.

The new study from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, published today in Science, presents an updated global surface temperature analysis.

The results reveal that global trends are higher than previously reported, especially in recent decades, and that the central estimate for the rate of warming during the first 15 years of the 21st century is at least as great as the last half of the 20th century.

According to the authors, when better corrections for various sources of bias were applied to the data the so-called global warming hiatus vanishes-and in fact, they argue, global warming may have sped up.

“These results do not support the notion of a “slowdown” in the increase of global surface temperature,” they write.

Our colleagues at the UK SMC collected the following expert commentary. Feel free to use these quotes in your reporting. If you would like to contact a New Zealand expert, please contact the SMC (04 499 5476; smc@sciencemediacentre.co.nz).

Prof Gabi Hegerl, Professor of Climate System Science at the University of Edinburgh, said:

“This result is really interesting and to me a bit surprising. It wouldn’t be the first time that an apparent data/model mismatch was resolved as being at least in part due to data issues.

“It shows how important it is to continue to improve our measurement and processing of data, and that we need multiple data sources in order to resolve tricky questions about data homogeneity and coverage. However, variability within the climate system will inevitably will yield periods with strong trends and periods with weak trends.”

Dr Ed Hawkins, climate scientist at NCAS, University of Reading, said:

“Observations of temperature over the past 150 years were made with a wide variety of instruments. Because measurement techniques have improved over time, corrections have been made to ensure the past temperature data is consistent and accurate.

“The process is never finished. Climate scientists continue to refine our understanding of past temperature changes. This update to one of the major global temperature datasets uses new information on measurement type to produce improved corrections which act to increase the global temperature trends over the past 15 years.

“This suggests that the much-discussed recent slowdown in global temperatures is far less pronounced than previously thought. In addition, estimates of climate sensitivity constrained by past observations may need a slight upwards revision, increasing the risk of negative consequences from our warming climate in future.”

Prof Mark Maslin, Professor of Climatology at University College London, said:

“This study is important and makes a significant step forward to the analysis presented in the IPCC (2013) report as it addresses three key areas of uncertainty.

“First, the study analyses and corrects for the different temperature measurements between floating buoy and ship data, as ship data is systematically warmer than buoy data. Globally this is a difference of 0.12?C. They also corrected the ship data. Prior to the Second world war there was a shift from bucket to engine intake thermometers, this was assumed to be a universal shift but recent analysis shows that some ships even today use bucket observations, which are always cooler due to evaporation.

“Second, the study makes use of the new data produced by the International Surface Temperature Initiative. This project started in 2010 to provide the very best data on surface temperatures. In five years they have double the number of stations available globally and ensured all the data in their data base is corrected for changes in station location, instrument changes, observing practice and urbanization. This data is a significant improvement on the data used in studies reported in the IPCC 2013 report. Third the authors took account of the incomplete data in the Arctic region, which has underestimated the warming in that region.

“The result of this study is that warming rates both of the short and long term are much more similar than previously suggested. The period 1880 to 1940 was not as cold as previously reported and that the warming trend from 1950-1999 was 0.113°C per decade, while from 2000-2014 it was 0.116°C per decade. This important reanalysis suggests there never was a global warming hiatus; if anything, temperatures are warming faster in the last 15 years than in the last 65 years.

“A whole cottage industry has been built by climate skeptics on the false premise that there is currently a hiatus in global warming. This is despite climate data showing continued warming of the Earth surface. Much of the media have latched on to this supposed slow-down as it continues the ‘for and against’ climate change debate. The weight of evidence for anthropogenic climate change is overwhelming and this new study shows that the global warming hiatus was just wishful thinking.”

Prof Sir Brian Hoskins, Chair of the Grantham Institute, Imperial College London, said:

“This reassessment of global temperatures, which gives that there has been no pause or slowdown in surface warming since 1998, is very important as it comes from an extremely well regarded group at a US Government laboratory.

“It has been known that the storage of the excess heat caused by increased greenhouse gases has continued, and it had been thought that the reduction in surface warming must be due to natural variation in the heat exchanged between the atmosphere and ocean. Now it appears that any such exchange of heat between the atmosphere and ocean has not been large enough to obscure the global warming trend, even in the relatively short period we have so far had in the 21st century. It also suggests that some of the lower estimates of warming that depend on the low trend in recent temperatures may no longer be credible.”

Prof Tim Osborn, Professor of Climate Science at the University of East Anglia, said:

“This is an important update to the NOAA global temperature dataset, one of a handful of such global temperature records that are used to monitor ongoing climate change. These records have to combine information from many types of measurement, and inevitably these have differences and biases that must be taken into account when calculating how the global temperature has changed over the last 150 years – and over recent decades too. Previous work has addressed many of the biases already, but more refinement can always be achieved as new data become available and as our understanding of the limitations of our measuring systems improves.

“More observations over land, especially in the high latitudes, and better corrections for biases in sea surface temperatures as the measuring systems have gradually changing from ship-based measurements to drifting buoys. Interestingly, similar improvements were already introduced to our global temperature record (the HadCRUT4 record, a joint endeavour of the Climatic Research Unit and the University of East Anglia and the UK Met Office) in 2012, though they did not make such a dramatic difference as they appear to do in the NOAA dataset. Understanding why this difference arises will need detailed analysis in the coming months.

“The long-term warming since 1880 is hardly affected by these updates, but estimates of warming trends over shorter periods are affected. The IPCC cautioned against drawing firm conclusions from short-term trends, but they did highlight that the warming over the 15 years from 1998 to 2012 may have been slower than the average warming rate since 1951 – and therefore it is interesting to understand this difference and its possible implications for our understanding of the climate system and our projections of future climate.

“This new study suggests that the slowdown in the rate of warming may be much less pronounced than in the global temperature records that were available for the IPCC to assess. The IPCC’s assessment wasn’t wrong, but perhaps the emphasis would be slightly different if the assessment were carried out afresh with the new studies since 2013 that could now be considered. One of the problems with the IPCC having 6-year assessment cycle is that it takes time for new findings to feed through to the assessments that inform decision makers and policy makers.

“Nevertheless, I would caution against dismissing the slowdown in surface warming on the basis of this study, nor to downplay the role of natural decadal variability for short-term trends in climate. There are other datasets that still support a slowdown over some recent period of time, and there are intriguing geographical patterns such as cooling in large parts of the Pacific Ocean that were used to support explanations for the warming slowdown. It will be interesting to see if these patterns are still present in the revised NOAA dataset (the new paper shows only the global average temperature). Furthermore, a key feature of the apparent slowdown in surface warming was that it left the observed warming close to the bottom of the range of climate model projections of warming during the last few years at least. The newly revised NOAA data can be used to update that comparison, though it’s not likely to resolve that issue.”

Dr Peter Stott, Head of Climate Monitoring and Attribution at the Met Office Hadley Centre, said:

“This is an interesting study which confirms that uncertainties in the global temperature record are one part of understanding the recent slowdown in warming. The slowdown hasn’t gone away, however – the results of this study still show the warming trend over the past 15 years has been slower than previous 15 year periods. While the Earth continues to accumulate energy as a result of increasing man-made greenhouse gas emissions these results also confirm that global temperatures have not increased smoothly. This means natural variability in the climate system or other external factors has still had an influence and it’s important we continue research to fully understand all the processes at work.

“Overall this study demonstrates the importance of further work in narrowing down uncertainties in global temperature datasets and in better understanding climate variability. These are areas the Met Office has been working on for a number of years. The numbers in this study are within the uncertainty ranges calculated in our own global temperature dataset and we’re in the midst of a long-term project to further improve our understanding and narrow the uncertainties. Understanding variability in the rate of global average surface warming is an ongoing and active research topic.”

Prof Richard Allan, Professor of Climate Science at the University of Reading, said:

“This study highlights the care that is required in turning measurements into a credible climate record.

“The most important new adjustment the authors make is to account for the changing coverage of ships and floating buoys which differ slightly in their temperature readings. Accounting for this discrepancy increases the temperature trend for the most recent period (since 1998) over the oceans and makes the recent global warming trends indistinguishable from those over the earlier 1950-1999 period.

“It remains a surprise that surface warming over the past 15 years is not larger than the 1950-1999 period which experienced quite slow global warming before the 1980s, in part due to a cooling effect from aerosol pollution and volcanic eruptions that counteracted the warming influences of greenhouse gas emissions.

“Warming was rapid in the 1980s and 1990s and it is curious that a comparison with these decades was not included in this new study. The past 15 years has undoubtedly been climatically unusual with atmospheric and oceanic circulation patterns unprecedented in the observational record.

“The authors importantly note that focus on understanding how climate varies from one decade to the next, motivated by unexpected and unusual changes in the oceans and atmosphere, is welcome and has advanced scientific understanding of our complex climate system.”

Prof Piers Forster, Professor of Climate Change at the University of Leeds, said:

“Getting data on global temperature for climate is always hard as these observations were always designed for monitoring weather and don’t necessarily have long-term stability. Despite this, long-term trends in global temperature are very similar between the 4 more or less independent datasets that exist. Even the corrections talked about in this study make very little difference to the long-term trend. (The 1951-2012 period on left hand side of their fig. 1). So they are not grossly flawed but remarkably robust. They are more flawed when looking at shorter-term changes in datasets.

“Does this mean there has never been a hiatus? It depends how you look at it. Even with the corrections in this study, the observed warming has not been as large as predicted by models. Other global datasets, even when corrected for missing Arctic data, still show a decreased trend since 1998. I strongly dispute that the IPCC report got it wrong on the hiatus, and I think this is where the study really misrepresents the IPCC. The IPCC made a very cautious and preliminary assessment of the hiatus acknowledging that the change wasn’t significant. Further, I would still expect other observed datasets to have a clear hiatus. As the IPCC report bases its assessment on more than one set of observations, I would expect its conclusions to still hold up today.

“Generally the IPCC reports try to capture an evolving science. This is challenging but important work and policy makers need the most up-to-date information possible to make informed judgments.

“The study makes the important point that we need to look really carefully at data quality and issues of instrumental change. Yet there are several legitimate judgment calls made when combining datasets to make a global mean-time series. I still don’t think this study will be the last word on this complex subject.”

Prof Jeffrey Kargel, Glaciologist at the University of Arizona, said:

“The results and conclusions reached by Thomas Karl and others are certainly in accord with what we are seeing amongst the world’s glaciers, where melting – retreat or thinning – is taking place very widely.

“The results are also consistent with broader disruptions in the global climate system that the world’s people are feeling. The idea being pushed blindly by some with vested interests that somehow the planet is not responding to continued emissions of greenhouse gases doesn’t make sense from a simple physics viewpoint; but the climate-change denialism also doesn’t sit well with people who can read the newspaper and watch the TV news about climate change in action and who can recognize the effects in their own experiences.”

Prof Peter Wadhams, Professor of Ocean Physics at the University of Cambridge, said:

“This is a careful and persuasive analysis, and I think shows clearly that the so-called ‘hiatus’ does not exist and that global warming has continued over the past few years at the same rate as in earlier years.”