Ultra-high frequency noise is imperceptible to the human ear but could be harming us, according to one researcher concerned with a lack of research into the phenomenon.

Writing in Proceedings of the Royal Society A, Prof Tim Leighton from the University of Southampton highlighted the high levels of ultrasound – sound waves with frequencies higher than upper limit of human hearing – in public places. Ultrasound is emitted by a range of electronic appliances and devices including televisions and speakers.

Writing in Proceedings of the Royal Society A, Prof Tim Leighton from the University of Southampton highlighted the high levels of ultrasound – sound waves with frequencies higher than upper limit of human hearing – in public places. Ultrasound is emitted by a range of electronic appliances and devices including televisions and speakers.

Prof Leighton suggests existing guidelines on exposure to ultrasound are based on weak evidence and that there is insufficient research on human subjects, and ultrasound measurements, to assess what the potential health risks are.

Our colleagues at the Australian SMC collected the following expert commentary.

Professor David McAlpine is a Professor of Hearing, Language & The Brain and Director of Hearing Research at the The Australian Hearing Hub, Macquarie University

“Can sounds you can’t hear damage your hearing? At birth, the human inner ear is sensitive to sound frequencies up to 20 kHz, and this upper limit gradually falls over the life course. Ultrasound – sound above this frequency might therefore be thought to be safe (although not for your dog).

However, whilst we don’t know all of the specific effects of ultrasound on human health and well-being – a question this paper is seeking to stimulate – there is little doubt that high intensity noise is damaging, and that higher frequency noise is more damaging than low. A potential consequence of damaging the inner ear by loud sounds is reorganization of the central auditory pathways – a form of neural plasticity that has been associated with tinnitus.

Ultrasound (or near ultrasound) frequencies has been used as a ‘deterrent’ to teenagers hanging around corner stores – on the basis that adults can no longer hear these sound frequencies. But why should shop owners be allowed to direct potentially damaging noise at teenagers to encourage them to move on? Babies (who also tend to hang around shops – and with little choice in the matter) might be affected more so.

Our understanding of the effects of loud noise on our communication abilities is changing rapidly – and is coming to the view that it is more damaging than we previously thought. This papers call for a review of current recommendations is timely.”

Below are comments collected by our colleagues at the UK SMC

Prof Jan Schnupp, Professor of Neuroscience at the University of Oxford , said:

“I have to declare that I am rather sceptical about this.

“It is true that there is a lot of ultrasound generated by appliances in the modern world. Fluorescent lights, for example, can emit quite a lot of sound above 20 kHz. I can also imagine that these ultrasounds might be annoying to pet dogs, cats or rodents who tend to have much more sensitive hearing at much higher frequencies than we do.

“However, the amount of physical energy in these ultrasounds is absolutely tiny, and almost none of those tiny amounts of sound energy will penetrate from the air into our bodies. It will just bounce harmlessly off our skin. Such a phenomenally tiny amount of ultrasound energy from the air will penetrate our bodies that it is quite hard to envisage it could do any serious damage.

“At the same time, literally billions of people have been exposed to ultrasound from fluorescent lights for many years and by and large living longer and healthier lives than their parents’ generation.

“While the author is correct in saying that we perhaps know less than we ideally would like about ultrasound levels in our environment, we nevertheless do know enough to be able to be fairly confident that it is very unlikely to be a significant health hazard to humans.

“My advice to would be to worry about the sounds you can hear, enjoy loud music (like alcohol or calorie rich foods) in moderation, exercise occasionally, have fun and leave it to the hypochondriacs to worry about the potential harms of ultrasound exposure.”

Prof Jonathan Ashmore FRS, Bernard Katz Professor of Biophysics at the UCL Ear Institute, said:

“This study has clear scientific deficiencies.

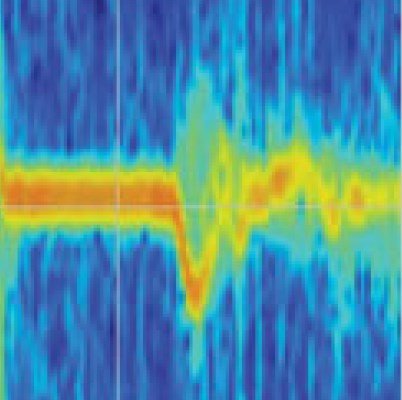

“There is little new data here, and that which there is (e.g. Fig 1) is not well controlled. When you see a really narrow band sound as is shown near 20kHz the chances are that it comes from the digital sound system, as many CD players – and even iPhones – sample at 42-44kHz which is remarkably close to 2x what is reported! Public libraries? Air conditioning systems are also liable to whistle, so the wobbles you see in the trace can easily be the effect of doors opening, people moving etc.

“Physiological evidence very strongly suggests that the ear does not pick up any airborne sounds much above 18 kHz, certainly in adults. If there are indeed real experimentally reproducible physiological effects then indeed more research needs to be done, but it might be more profitable to look for other mechanisms, for example on the vascular system, before going for this. This issue came up several decades ago when hospital ultrasound machines became widely available.”

Dr Martin Coath, Associate Lecturer at Plymouth University, said:

“The first thing to clear about is that this work is pretty uncontentious. The author is simply calling for a detailed re-examination of a load of outdated guidelines and the revisiting of decades of results that suggest there might be a problem but have not been pursued with sufficient vigour or rigour. At this level the study reads – and this is not a bad thing – like a grant application.

“The measurement of noise levels, and the assessment of the effects they have on human health, are both inexact sciences. Noise that has always been almost impossible to perceive and much more difficult to measure has been widely ignored. The author’s point is that it is high time that the examination of ultrasonic ‘pollution’ achieved a level of inexactitude comparable with other types of noise.

“Ultrasound is a silent companion to everything we do. We make it when we rub our hands together or when we wrap food in aluminium foil – in fact when we do pretty much anything. The degree to which we should control processes that make a heck of a lot of ultrasound at high enough levels to make people uncomfortable or unwell needs to be debated and for that we need loads more evidence than we have.”

Dr David McGonigle, Research Fellow at Cardiff University, said:

“The title of this study may make one rather alarmed – ‘Are some people suffering as a result of increasing mass exposure of the public to ultrasound in air?’ – but it is less concerned with presenting new data on the topic than offering a ‘state of the nation’ summary of the field.

“Scientific papers take a number of forms: some focus on reporting the results of experiments that the authors themselves have performed, whilst others, like this study by Professor Leighton, seek to summarise and review work across a broad range of sources and disciplines. While its title may suggest otherwise, the paper actually does not present evidence to link mass ultrasound exposure to subjective symptoms like headaches or vertigo in the public. This is because – and it is a point acknowledged by the author – that there has yet to be a double blinded, controlled trial of such an exposure, which would ensure that people’s reporting of symptoms is not biased by their knowledge that they are currently being exposed to ultrasound.

“This kind of study is required because subjective reports of people’s symptoms are rarely accurate or well controlled – as is often stated ‘the plural of anecdote is not data’ – but the paper does demonstrate that industry standards may need updating, and larger sample sizes are required to ascertain if a link between exposure and symptoms does exist.”