After months of unrest, Mt Agung on the Indonesian island of Bali is finally erupting. The island was elevated to the highest level of volcanic alert on Monday morning.

Mt Agung has been spewing gas and ash since last week, and over 100,000 residents living near the volcano have been ordered to evacuate from a 8-10km exclusion zone. Denpasar airport has been closed since Sunday, leading to hundreds of cancelled flights. On Tuesday, lahars (volcanic mudflows) began racing down the mountainside, flooding rivers and canals of nearby villages.

The SMC asked experts to comment on the eruption, please feel free to use these comments in your reporting.

Dr Nico Fournier, volcanologist, GNS Science comments:

“Over two months after some unusual activity was first detected at Mt Agung, the Balinese volcano finally erupted on November 21, 2017, ejecting ash across Bali and the neighbouring island of Lombok.

“While it remains unclear what the volcano may have in store over the coming weeks, it has already taught us a major lesson: not to unreasonably fear the dreaded crying wolf syndrome.

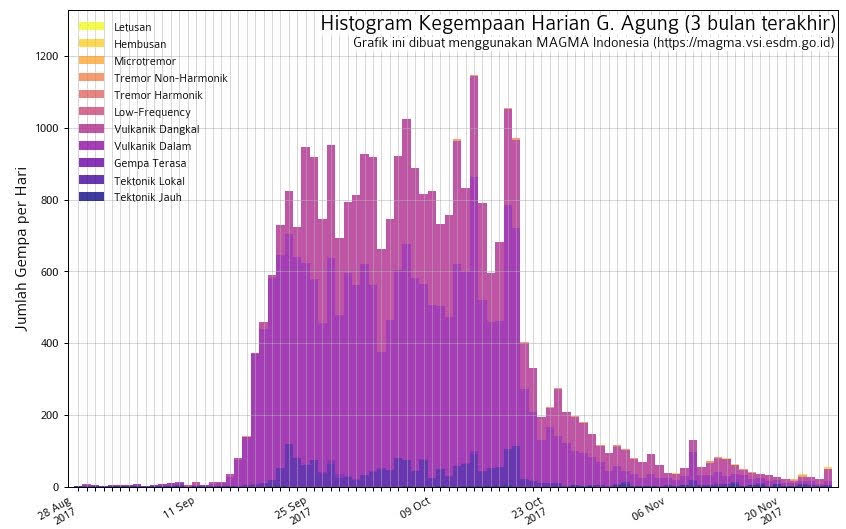

“Earthquakes were recorded early on, suggesting that the volcano was entering a phase of unrest. This caused the scientists to raise the alert level and the authorities to initiate the early evacuations of over 120,000 people. But the early signs of unrest subsequently decreased dramatically a few weeks prior to the eruption, leading to a sustained period of relative calm.

“It could have gone either way: the hasty repatriation of population closer to the volcano due to increasing peer, political and financial pressure or, as it happened, the realisation that the lack of recorded activity did not mean the end of the crisis just yet.

“Volcanoes simply work on their own terms, and there is always a substantial level of uncertainty in forecasting natural hazards and their impact. In Bali, the unwavering resolution of both the population, the authorities and the monitoring scientists resulted in a remarkable success story that is for us all to reflect on.”

Graph showing the number and types of earthquakes recorded at Mount Agung every day since the beginning of the present crisis. Evacuations were triggered at the high of the seismic crisis but the volcano then got quiet for weeks prior to the eruption. This is not untypical but reflects the difficulty to accurately forecast when an eruption may occur. Source: MAGMA Indonesia, PVMBG

Brad Scott, volcanologist, GNS Science comments:

“The Agung eruption is of interest to New Zealand volcanologists and in particular the Taranaki Regional Council as the volcano is very similar to Mt Taranaki. Lessons from this eruption will inform volcano monitoring, volcanic unrest studies and how to respond to an eruption of this size in New Zealand.

“Mt Agung is on Bali Island, a popular visit for many New Zealanders. It is the highest point on Bali and dominates the surrounding area, influencing the climate — especially rainfall patterns. From a distance, the mountain appears to be perfectly conical and has a summit crater. The volcano has had significant eruptions in 1843 and 1963-64. Many lives have been lost during past eruptions.

“The local volcanological organisation has done a great job monitoring the volcanic unrest (the volcano waking up), via the local Volcano Alert system (VAL) and they have communicated the unrest [to the public] by raising the VAL level as the unrest increased.

“They have also set up evacuations to create safe zones about the volcano. Local residents and visitors will be safe as a consequence. The local information has also been communicated internationally, albeit with some misreporting.

“The VAL is now at level 4, the highest level for the Indonesian system. Each country has its own VAL system to take account of factors like local cultures, level of monitoring, local CDEM arrangements etc. The NZ system has 6 levels.

“The eruption is likely to have a significant local impact, with ashfall and lahars been the biggest issues. Remobilisation of the volcanic ash in the wet season rains will be a big issue to manage, along with international aviation.”

The Australian and UK Science Media Centres also gathered expert commentary on the eruption, please feel free to use these comments in your reporting.

Associate Professor Heather Handley is an ARC Future Fellow in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Macquarie University

“After a lengthy period of earthquake activity in September and October 2017 caused by magma (molten rock) intruding at shallow levels beneath Mt Agung, the volcano had a small water-driven eruption (phreatic) on the 21 Nov. This was followed by a larger magma-driven eruption, which started on the 25 Nov and is continuing.

“The current eruption has produced a high column of grey-black ash, which is composed of tiny, sharp, rock fragments and gas. The ash plume has reached 3,000 metres above the summit of the volcano. Exploding lava in the crater has been reported by the Indonesian National Disaster Management Authority.

“The status of Mount Agung has been raised from standby (level 3) to alert (level 4) starting from 27/11/2017 at 06:00 WITA. The Indonesian Centre for Volcanology and Geological Hazard Mitigation has recommend a no-go zone with a radius of 8-10 km around the volcano. The situation is considered dynamic and could change at any time. People are encouraged to evacuate in an orderly and calm manner.

“A NASA Satellite has detected sulphur dioxide (SO2) emissions from the volcano spreading east-southeast of Agung over Lombok.

“The most significant volcanic hazard at present is from falling volcanic ash. People are advised to wear masks and eye protection and stay indoors.

“People traveling to/from Bail are advised to check with their airlines and tour operators as several airports in the vicinity have been closed.”

Prof Bill McGuire, Emeritus Professor of Geophysical & Climate Hazards, University College London, said:

“While the situation is currently uncertain, Mount Agung has the potential for a major eruption that can impact upon the global climate as well as upon the local area. The last eruption in 1963, scored a five on the Volcano Explosivity Index, putting it roughly on a par with the 1980 eruption of Mount St Helens (Washington State, USA).

“That 1963 blast killed up to 1500 people on Bali, and also had an impact on the climate. Agung’s eruptions seem to be very rich in sulphur, which has a significant cooling effect if it gets into the stratosphere. The 1963 blast resulted in the formation of a veil of sulphuric acid particles in the stratosphere that spread across the planet, reducing global temperatures for several years.”

Prof Mike Burton, volcanologist, University of Manchester, said:

On the main dangers if the volcano erupts:

“The main hazards are pyroclastic flows and lahars. Pyroclastic flows have two main causes, firstly the collapse of lava accumulating in the summit area, which produces a hot rock avalanche, entraining cooler air and accelerating as it flows down the flanks of the volcano. These flows can extend for several kilometres from the summit. The second source of pyroclastic flows is eruption column collapse, when a volcanic explosion erupts a large volume of rock into the atmosphere, which then falls back down around the summit area, producing hot rock avalanches again, but this time with greater energy.

“Lahars are flows of mud and volcanic ash, which can be easily mobilised when freshly deposited ash is carried by the intense rains in the Indonesian rainy season. The most intense rains usually occur between November to March, so an eruption in the coming weeks could lead to lahars quite quickly. These mud flows are extremely hazardous as they can flow quickly and for long distances, scouring the land and damaging infrastructure, as well as posing a threat to life.

On whether there will be a lot of casualties like last time Agung erupted:

“The probability of a large number deaths and injuries is much lower now than it was in 1963, as modern volcano monitoring techniques have improved, there is much better awareness of the hazards posed by explosive eruptions and, most importantly, local populations are better informed, with clearer communication links. Therefore, planning for a scenario similar to the 1963 eruption with pyroclastic flow run out up to 12 km from the summit is prudent, with a good probability that the actual eruption will be smaller than that.

On monitoring events and the role of social media:

“The current unrest on Agung may well lead to an eruption, and it will be closely monitored by the Indonesian authorities, who have already taken preventative action by evacuating local populations. This unrest is being followed attentively by many people on Twitter and other internet sources, with continuous live updates, so any change in activity will be known worldwide within minutes.

On other dangers from an eruption beyond Bali and the local area:

“Apart from the local impact, an explosive eruption from Agung could affect air traffic through the dispersal of ash into the atmosphere, and climate, through the injection of Sulfur dioxide (SO2) and Hydrochloric acid (HCl) into the stratosphere. The danger posed by ash to aircraft is that the ash melts within the jet engine, and then accumulates and solidifies on a cooler rotor, eventually blocking the engine entirely.”