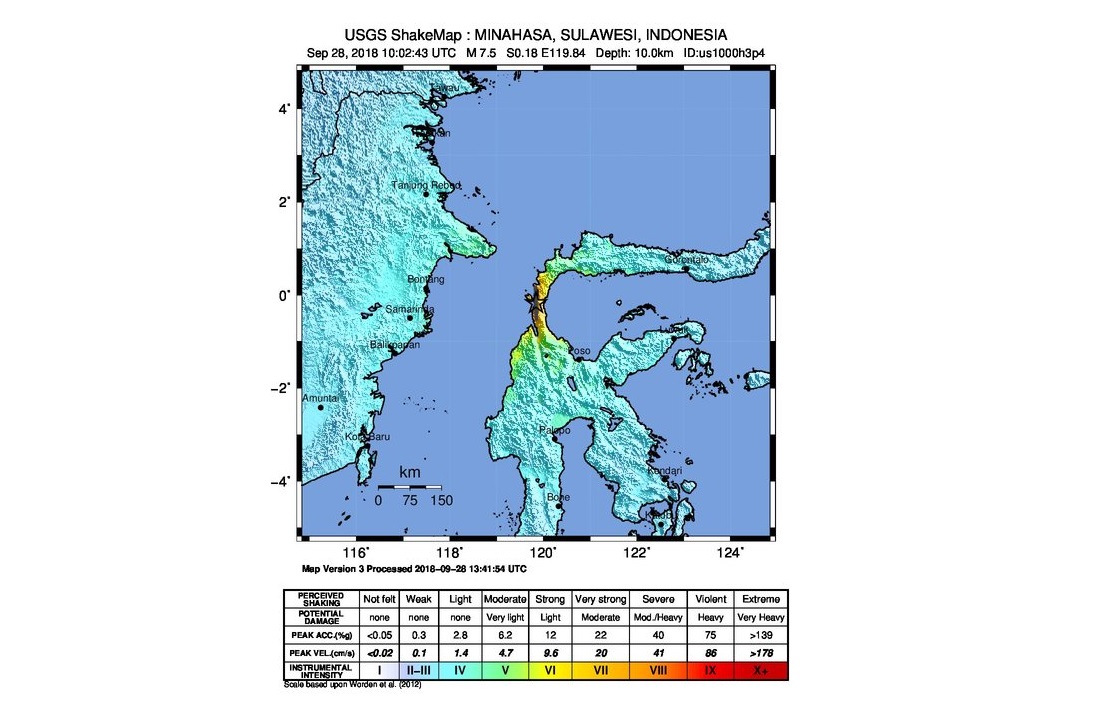

On Friday Evening, a 7.5 magnitude earthquake struck near the city of Palu on the island of Sulawesi.

After the mainshock, a 0.5-3.0m tsunami alert was issued for the Makassar Strait (which separates Sulawesi from Indonesian Borneo) and a 0.5m alert for Palu. This alert was called off after an hour, but later a localised tsunami with waves at least 5m high swept into the city of Palu. The quake and resulting tsunami killed at least 800 people and displaced more than 50,000. These numbers are expected to grow as the rescue teams reach areas cut off by landslides.

GNS Science seismologist John Ristau told Stuff that the type of earthquake and the magnitude (M7.5) weren’t usually associated with causing tsunamis.

On Tuesday, Foreign Affairs Minister Winston Peters has announced New Zealand will provide $1.6m to assist Sulawesi earthquake and tsunami response.

The SMC asked experts to comment on the disaster. Please feel free to use these comments in your reporting.

Dr Jose Borrero, Director eCoast Marine Consulting, comments:

“This was a somewhat strange event in that the earthquake source was a strike-slip event which means there is relatively little vertical deformation and therefore relatively little tsunami generation potential compared to a subduction zone type earthquake which has a ‘thrust’ type mechanism.

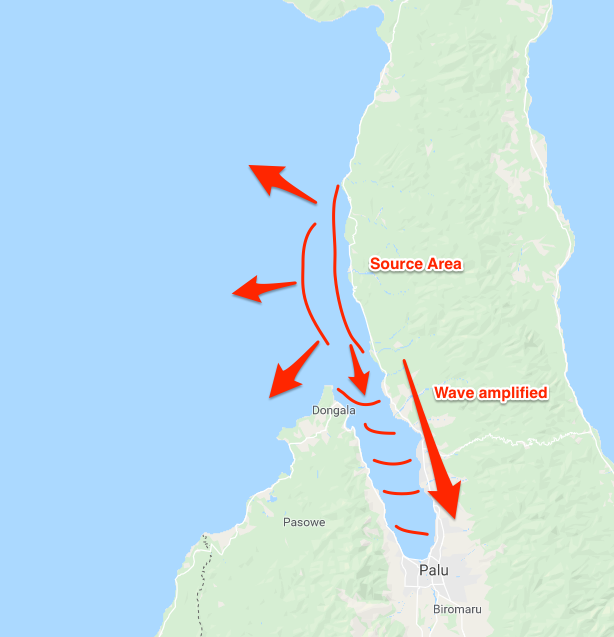

“But there have been many documented cases of tsunamis generated in association with strike-slip events in Indonesia and other places. Note that I didn’t say ‘caused by’ a strike-slip earthquake, because there could be some sort of a secondary mechanism involved like a submarine slump, or by the lateral motion of the land itself.

“Undoubtedly, a factor in the size of the wave will be the fact that Palu is located at the head of a long skinny bay, so any wave that is forced up the bay will be strongly amplified at the head of the bay. The Videos going around the internet are from Palu right at the head of the bay.”

“Similar effects were seen in Pago Pago Harbour (a long skinny bay) in American Samoa after the 2009 Samoa event.”

Dr Willem de Lange, University of Waikato, comments:

“We undertook an assessment of the tsunami hazard of the Makassar Strait region of Indonesia, which included the west coast of Sulawesi, in the late 1990s. This area was identified as a high-risk region with six major tsunami events between 1900 and 2000 within the Strait (one-third of Indonesian events last century).

“An aspect of concern was that some events produced localised large tsunamis that exceeded the magnitude we would expect from the size of the earthquake. This suggested that submarine landslides contributed extra energy to the generated tsunami waves, increasing their size.

“Unfortunately this complicates providing reliable warnings, as the waves can be larger and arriver sooner than predicted.

“Based on the magnitude of the earthquake, authorities warned of possible tsunami waves between 0.5 m and 3.0 m. Observations reported in the media, indicate that their predictions were reasonable for most locations, but that some areas may have experienced larger waves than predicted in the warnings.”

Joint statement from GNS Science and the Ministry of Civil Defence and Emergency Management GNS Science:

“It’s unclear what caused the devastating tsunami in this tragic event. Scientists have a reasonable understanding of the earthquake, but not the precise cause of the tsunami. While we don’t have all of the details on Indonesian warning arrangements, it’s a timely reminder of what to do in New Zealand, where we are also prone to local earthquakes that can generate large tsunamis.

“This event reinforces the importance of natural warning self-evacuation often referred to as ‘Long or Strong, get Gone’ for coastal regions that are close to and feel large earthquakes. Most of the time that a local earthquake generates a large tsunami, where felt shaking occurs, strong shaking is the first and most reliable warning in the closest coastal areas that a tsunami may be coming.

“Meanwhile for life safety, self-evacuation is important and every minute counts after the long or strong earthquake. People should not wait for anything, they must know their evacuation zone and routes and walk, run or cycle immediately to safety.

“New Zealand has official warning systems in place, including enhancements to the national geohazards monitoring programme, GeoNet, and the use of Emergency Mobile Alerts, to support felt shaking. These systems will be used when possible, and as soon as practicable in any tsunami event, noting the first waves may arrive before these official warnings are issued.”