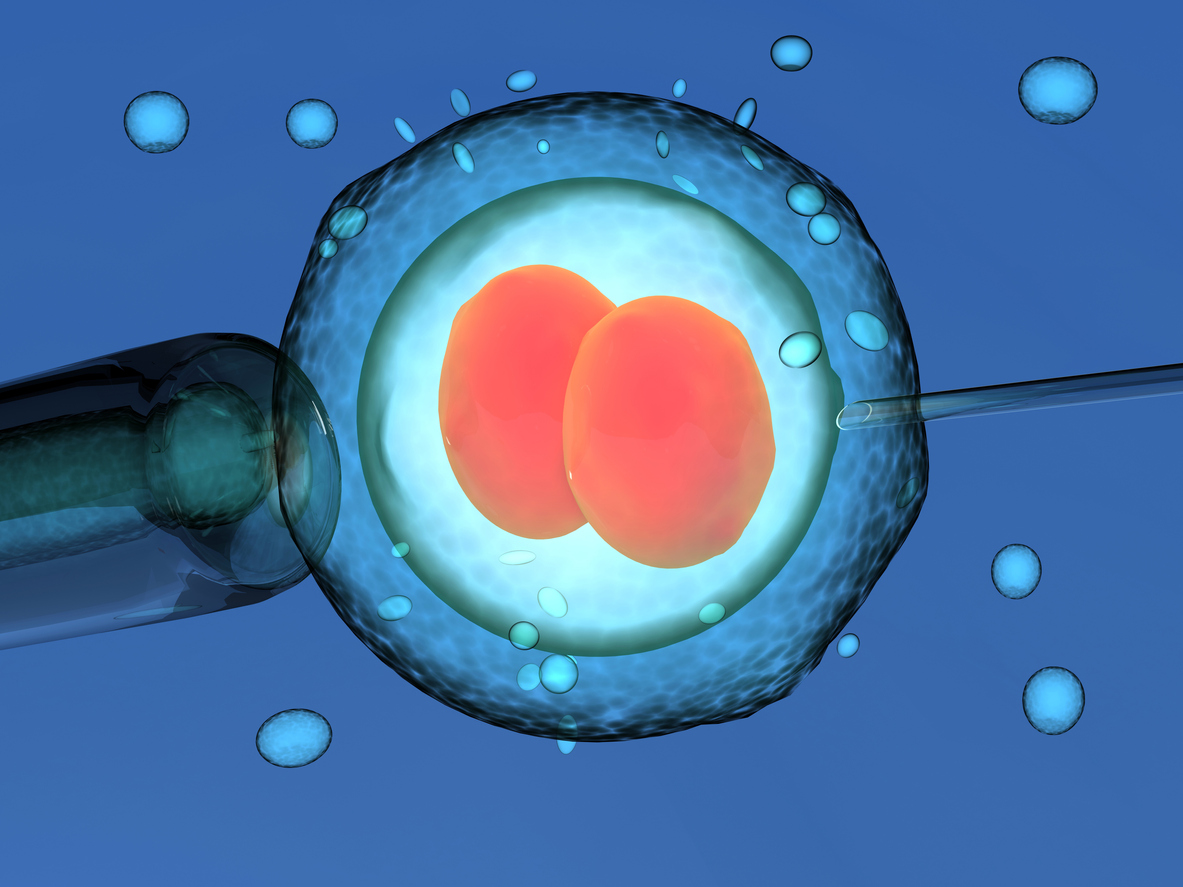

Chinese researchers have claimed to have used CRISPR gene editing in human embryos that have resulted in the birth of twin girls – one with the edited gene and one without.

Associated Press is reporting that the twin girls were born earlier this month, which would make the gene-edited twin the world’s first genetically edited baby. The scientist claims to have altered the embryos to make the babies resistant to HIV – the virus that causes AIDS.

The SMC asked a New Zealand expert to comment on the reports. Please feel free to use these comments in your reporting.

Dr Jeanne Snelling, Lecturer, Bioethics Centre and Faculty of Law University of Otago, comments:

“These reports are extremely concerning – for several reasons.

“1. Most of the international scientific community agree that it the science is far too premature for CRISPR research to be used in a clinical context. In addition, the ethical issues are still being debated at an international level.

“2. The gene that was edited was not associated with a serious condition, in fact this was essentially an unnecessary enhancement procedure that would be associated with risks that do not have offsetting benefits. These risks include off-target effects – where an unwanted alteration may occur that causes ill-health in the individual that is born.

“3. Such research is unlawful in NZ – implanting a genetically modified embryo in a woman is prohibited under the Human Assisted Reproductive Technology Act 2004.”

No conflict of interest.

Our colleagues at the Australian and UK SMCs also gathered the following comments, feel free to use them in your reporting.

Dr Ainsley Newson, Associate Professor of Bioethics at the University of Sydney, comments:

“While this research has yet to be subject to peer scrutiny (which in itself is problematic), it looks like the researcher involved wanted to be the first rather than waiting to be safe. It is still early days for human genome editing; with lots of scientific and ethical issues needing to be ironed out before it is used to change a genome of an embryo and its future descendants.

“Susceptibility to HIV infection is not an obvious target for genome editing. We don’t need genome editing to prevent HIV – we need to make existing preventive measures and treatments more widely available. Editing the DNA of healthy embryos to reduce the risk of contracting HIV is neither necessary nor appropriate.

“This announcement also risks undermining the very careful research being undertaken globally to investigate the safety and future potential uses of genome editing to help avoid children being born with severe, life-limiting diseases.

“If it is shown that these twin girls have indeed had their genomes edited, I hope that they are supported both medically and socially as they grow up; without becoming public curiosities.

“Every position statement that I’ve seen globally has condemned the editing of human embryos for reproductive use at this point in time. What seems to have happened would be illegal in Australia and carries a criminal penalty here.”

No conflict of interest declared.

Associate Professor Darren Saunders, gene technology and cancer specialist in the School of Medical Sciences at the University of New South Wales, comments:

“Important to note that at this stage the reports have not been independently verified so it’s hard to say if the claims are real. Scientists everywhere today will be thinking “show me the evidence” and some of the claims from the scientists involved suggest that the gene editing was only partially successful. If confirmed, this represents a huge technological and ethical leap. It’s possible we just saw a huge leap towards editing the human book of life – some might even suggest this is a step towards eugenics.

“Even seeing the detailed data may be tricky. No reputable scientific journal should touch this story if the experiment was done without the appropriate ethical approval (as seems likely from comments attributed to the scientists involved). This aspect of the story is really problematic and disturbing. Experiments like this risk setting back the entire field. Science operates under a social licence – scientists work within limits defined by broader community concerns. Ignoring those boundaries risks a justified backlash and fear that can set back the entire field by decades.

“Most scientists think that the safety concerns around gene-editing in humans are still too big to outweigh any potential benefit. We don’t know the long-term effects of CRISPR editing in humans. There are significant safety concerns are around the possibility of “off target” gene edits (ie editing unintended genes) and the tendency for editing to work most efficiently in cells where a major tumour suppressor gene (p53) is silenced.”

No conflict of interest declared.

Dr Yalda Jamshidi, Senior Lecturer in Human Genetics, St George’s, University of London, comments:

“Gene editing tools are fantastic for research but we are still not able to control them well enough to ensure they are safe and efficient for use in humans. The scientists who carried out these studies chose to focus on a gene associated with risk of HIV, however we already have ways to prevent HIV infection and available treatments should it occur.

“We also do not need gene editing to ensure it isn’t passed on to offspring. We know very little about the long term effects, and most people would agree that experimentation on humans for an avoidable condition just to improve our knowledge is morally and ethically unacceptable. Whether the results stand up to scrutiny or not we need as a society to think hard and fast about when and where we are willing to take the risks that come with any new therapeutic treatment, particularly ones that could affect future generations.”

Prof Paul Freemont, Co-Director of the Centre for Synthetic Biology and Innovation, Imperial College London, comments:

“I am shocked and disappointed about this work as it is absolutely not clear as to who benefits from this research. Genome editing is a powerful technology with huge benefits – however if this research is proven then it has resulted from no consultation with broader stakeholders and is merely showing technically what might be possible.

“Everyone in the field already knows what is possible and proving that one can do something technically does not make it acceptable. With the dawn of a new era of genetic technologies it is absolutely essential that the application of such technologies has societal and broader stakeholder approval and this work clearly goes beyond this.”