If you haven’t had the MMR vaccine, catching measles can cripple your immune system for years.

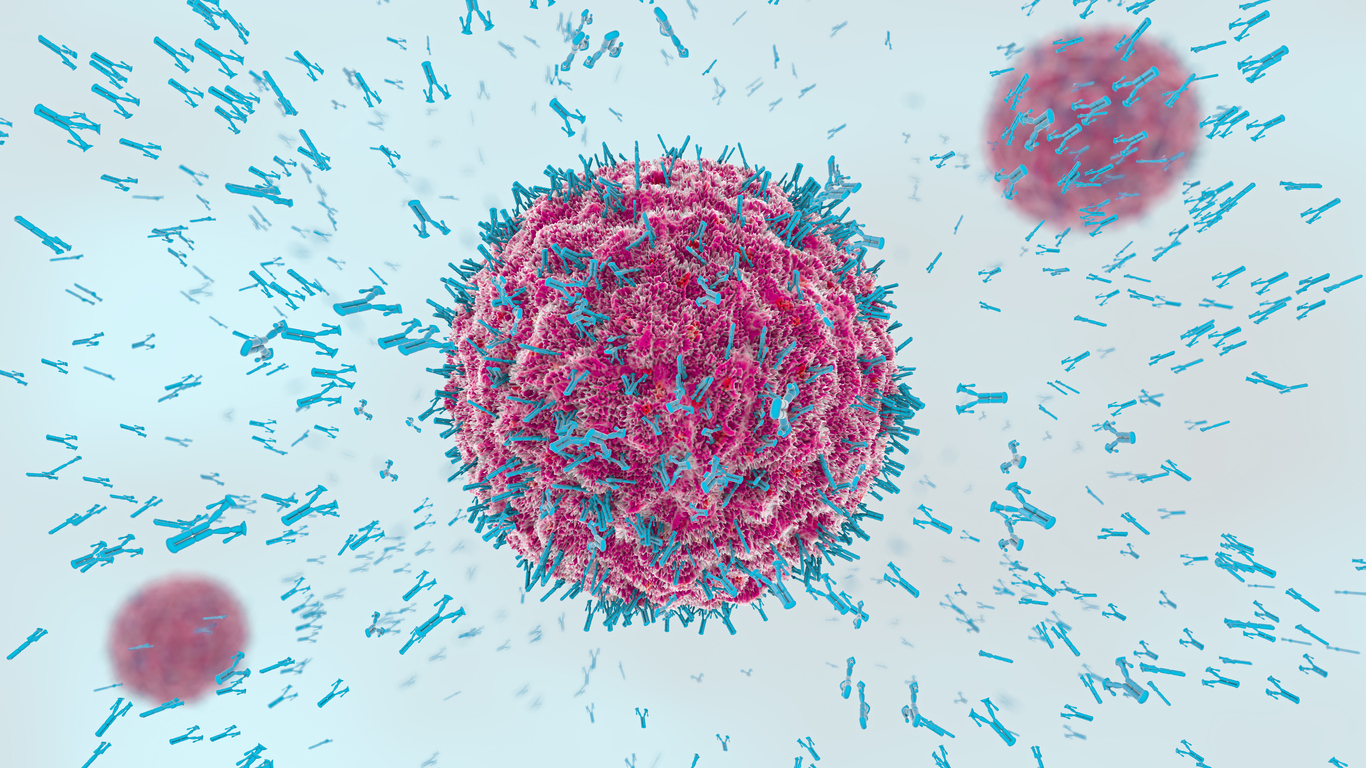

Two separate studies examining the immune systems of unvaccinated children before and after measles infection found that the disease creates a kind of immune amnesia that leaves you more vulnerable to future viral and bacterial infections. Luckily, the vaccine prevents this immune amnesia and saves you from lots of other nasty bugs.

The studies were published today in Science and Science Immunology.

The SMC gathered expert comments on the studies.

Professor Michael Baker, University of Otago, Wellington, comments:

“These papers provide more evidence to support the protective effect of measles vaccination. The potentially devastating effects of measles infection are well known. These papers provide evidence about the less well-known effects that measles infection has on the immune system.

“Measles infection has a severe immune suppressive effect with the majority of measles-associated deaths due to secondary infections. This immune suppression is still evident in 10-15% of children five years after measles infections, making them more vulnerable to secondary infections. These two reported studies have honed in on the mechanisms underlying this immune suppression. One of these studies showed how measles infection can eliminate a large proportion of protective antibodies in humans, leaving them more vulnerable to other infections. The other study demonstrated mechanisms for how this effect can operate at the cellular level and increase the severity of infections, such as influenza, following measles infection.

“These studies add to the increasing epidemiological evidence around the non-specific beneficial effects of vaccines, such as Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine and rotavirus vaccine. BCG vaccine, given to prevent tuberculosis, is associated with reductions in a wide range of infectious diseases and lowered child mortality in general. Rotavirus vaccine appears to offer partial protection against development of type 1 diabetes in children.”

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts. Member of the World Health Organization Regional Verification Commission for Measles and Rubella Elimination.

Dr Helen Petousis-Harris, University of Auckland, comments:

“There is an old urban myth that having measles makes you stronger. It does not: it makes you weaker, something that has been known for over one hundred years. In fact, an increase in overall death and a decrease in health after measles occurs for as long as five years after recovery. This is so severe that in less developed countries it is thought that, before vaccination, measles may have been responsible for up to half of all childhood deaths from other infectious diseases due to a suppression of the immune system. How does the virus do this?

“Measles virus infects some of the most important cells of the immune system and during its stay wreaks havoc. In just a few days it can infect up to 70% of important immune memory cells. The specific ways in which measles destroys immunity is now being elucidated and it is a multipronged attack. Importantly, measles virus replaces immune memory cells (immunity you had already established) with new measles-immune memory cells. Ironically, the immune memory made against measles is fantastic but the host has an increased vulnerability to other pathogens.

“One of the most familiar types of molecules of the immune system are antibodies. The Mina study found that among unvaccinated children who had even mild measles infection there was an elimination of around 20% of the antibody repertoire (diversity), 12 out of 77 children lost over 40% with the highest 73% after severe measles. Only once the children became re-exposed to the bugs they had previously become immune to did their immunity regenerate. Importantly, this negative effect was not observed in children vaccinated against measles.

“The Petrova study showed that after measles infection in humans, the pool of B-cells (these are the cells that make antibodies and also provide long-term memory, i.e immunity) go back to being immature. The long-lived memory B-cells that protect against many diseases are depleted. To better understand the potential consequences of this they used an animal model whereby they took ferrets that were immune to influenza and gave them a measles infection. After recovery from the measles the ferrets had increased severity of the flu they were previously immune to.

“New Zealand has been experiencing the most significant measles epidemic since the 90s with almost 2000 cases as of the end of October. There have been many smaller outbreaks prior to this. This year a third of cases (>600) were so severe they required hospitalisation, some received intensive care for an extended period. The vast majority of these cases were unvaccinated.

“During this epidemic, there have been many conversations on social media where people expressed their delight that measles was strengthening their child’s immune system. Obviously this is not the case. The risks of not vaccinating against measles have never been clearer, several people almost lost their lives this year because of measles, and two unborn babies died. These new studies highlight how those who were infected are likely to have ongoing health problems for several years to come, at both a personal and family cost, as well as a cost to the health system.

“The two key messages here are:

- Measles virus can severely damage previously acquired immunity to many diseases

- Vaccination against measles prevents this immune amnesia and the potentially-serious consequences.

“Measles is to be avoided!”

Conflict of interest statement: Helen has led a number of industry-funded studies. These have all been investigator conceived and led. She does not receive honorarium from industry personally. She has received industry support to attend some conferences and has contributed to Expert Advisory meetings for GSK, Merck, and Pfizer.

Dr Nikki Turner, Director, Immunisation Advisory Centre, University of Auckland, Chair of the Measles Rubella Working group to SAGE (Strategic Advisory Group of Experts) to the WHO, comments:

“The direct effects of measles infection are well quantified. However, it has also been known for a long time that measles virus has strong immunosuppressive effects on the immune system more broadly, lasting up to several years, possibly for as long as five years after infection and leading to increased morbidity and mortality broadly from other infectious diseases.

“Observational studies consistently show that when measles vaccination is introduced unexpectedly large reductions in all-cause childhood mortality have been observed, with reductions of up to 40 – 90% (Mina et al JID 2017). For example, in low income setting deaths from all-cause diarrhoea drops by almost 50%. In high income settings mortality rates are lower, but the effect on both mortality and morbidity is still clear. Research (Mina et al Science 2015) using high income country data, suggested that when measles virus was common (i.e. prior to vaccination) measles infected over 95% of all children and could have been implicated in as many as half of childhood deaths from all infectious diseases.

“The mechanism behind these effects are not yet entirely clear. These two papers have given further immunological understanding to the mechanisms of why, after you have been infected with measles, your immune system will have less ability to fight a range of infectious diseases for several years. Petrova et al. demonstrate measles virus both affects naive B cells on their subsequent ability to diversity and also has effect on reducing previously-generated immune memory. Mina et al. report that measles virus can infect 20 – 70% of memory cells and is associated with large reductions in the diversity of subsequent antibody repertoire and functioning. Of importance for public health vaccination programmes is that the same effect is not seen with use of the live attenuated MMR vaccine.

“So what does this mean from a public health perspective? The true extent of the public health consequences of measles is likely to be underestimated. We cannot absolutely quantify how big these broader effects of measles vaccination are, but they are clearly hugely significant. It is likely that the reduction in morbidity and mortality from the effects are even greater than direct effects. So when the WHO reports that measles vaccination averted more than 21 million deaths from 2000 to 2017, we could possibly even double that amount if we count the indirect effects.

“For New Zealand, as a high-income country, death is less common from childhood infectious diseases, but the use of measles vaccination will be significantly reducing overall hospitalisation rates, primary care usage and overall childhood (and parent) misery from a broad range of infectious diseases. A very interesting recommendation from Mina et al. was the suggestion that children who have had measles could be re-vaccinated to mitigate the suppressive effects on loss of immune memory.

“Our current health messages for the use of measles vaccination are pitched to the specific reduction in measles-related effects. This is compelling in its own right. We can add in these broader messages around how the measles virus affects the immune system leading to increased rates of many infectious diseases, and why measles vaccination is so effective beyond just measles prevention. However, the reasons for why people choose to decline measles vaccination are likely to be more around lack of trust in the science, scientists, health authorities and policy makers, not lack of evidence.

“My sound bite: The measles virus is a little bastard in its ability to reduce the immune system response to many infectious diseases for many years after an infection. Measles vaccination is one of the greatest public health advances we have ever had, and its effects are way beyond just measles protection.”

No conflicts of interest.