The novel coronavirus continues to spread, with the World Health Organization reporting that the virus has killed 81 people and infected more than 2,700.

Speaking to media yesterday the Director-General of Health Dr Ashley Bloomfield said the likelihood of coronavirus arriving in New Zealand was high. Today, the Ministry of Health has set up the National Health Coordination Centre.

Cabinet is expected to decide whether to make the virus a notifiable disease this afternoon, which would give health officials the power to quarantine infected individuals.

More information about the virus and advice for travellers can be found on the Ministry of Health website.

Below are comments from experts on the following aspects of the outbreak:

- Predicting the spread of the disease

- The psychological dimensions of viral outbreaks.

- The animal origins of the virus.

The SMC gathered expert comment on the virus.

Professor Mick Roberts, Professor in Mathematical Biology, Massey University, comments:

“Predicting the spread of a novel virus requires estimates of the basic reproduction number: the expected number of secondary cases due to a typical primary case over the course of its infectious period. A recent report from Lancaster University has suggested that the novel virus from Wuhan has a basic reproduction number of 3.8. Coupled with biological properties assumed to be similar to those for SARS, and assumptions concerning travel and contact patterns in China, a set of predictions were presented. These prompted a British tabloid to headline “ZOMBIELAND Coronavirus will infect 350,000 in Wuhan alone experts say…”

“The 350,000 is the upper 97.5% of the report’s prediction, and based on no changes in transmissibility until February 4. In other words no travel restrictions or behaviour changes reducing contact rates. Under these conditions, the predicted mean was 250,000 cases.

“The report from the Imperial College group to the WHO estimates the basic reproduction number to be 2.6, which results in lower predictions of future epidemic size. All estimates so far assume that the novel virus behaves like SARS. As further data become available better predictions will be possible.”

No conflict of interest.

Dr Sarb Johal, psychologist, comments:

On quarantine:

“There will be a Cabinet meeting today here in New Zealand and over further days to discuss powers of quarantine – but this has implications too. What we are seeing in terms of restriction of movement in China is unprecedented.

“Quarantine doesn’t come without risks. I wrote a paper back in 2009 published in the New Zealand Medical Journal outlining some of the psychosocial challenges involved in quarantine, including, how many patients experienced social stigmatisation and loss of anonymity and many described the emotional strain of quarantine and isolation.

“Parents had to confront changes in normal roles and routines, creating stress for entire families. Most found it difficult to explain the situation to their children without provoking more fear. Healthcare workers felt a duty to protect their children from being taunted or stigmatised by association. Spouses were physically isolated, for example, partners slept in separate rooms and were subjected to further pressure as they assumed responsibilities involving the outside world, such as school runs and shopping, as well as normal routine activities.

“In addition to the physical isolation, healthcare workers experienced isolation and stigma as a result of their exposure to SARS. Although most workers rationalised this as a lack of understanding about the illness or the risks involved, all described feeling angry and hurt. Even after the outbreak had been contained and individuals’ quarantine had ended, workers remained acutely aware of others’ reactions. To avoid the negative response, one worker even denied being a healthcare worker from the affected region.”

On community cohesiveness:

“We have also seen how health workers who work in situations like this can be shunned and stigmatised by their own communities for fear of transmitting and infection they maybe they picked up at work. And this stigma may also be extended to their family members, such as their children being treated differently at school. Or ostracised by their peers, or worse still, their teachers. We have certainly seen this in New Zealand, and it was reported in Singapore and Hong Kong during the SARS outbreak too.

“But with fracturing between communities and travel restrictions meaning that families who are meant to be together in this holiday period, where it may be the only time in the year that they get together, means that the social capital that would usually exist to help people get through something like this is somewhat eroded. People can feel lonely, and isolated, with little sense of when things may return back to normal. Further than that, they may also experience stigma and ostracism if they are isolated outside their home community.”

Note: These comments have been excerpted from Dr Johal’s blog where he discusses several other psychological aspects of the outbreak and has also posted a recording of a livestream on the coronavirus, including a Q&A.

Note: Dr Johal is a clinical psychologist who has been working in the field of Psychosocial Support and Recovery in Disasters since 2006. He was the lead writer for the UK Pandemic Preparedness Plan published in 2011 and led the teams on the NZ plans for pandemic preparedness and psychosocial support & recovery, published in 2007 & 2016.

Professor David Hayman, School of Veterinary Science, Massey University, comments:

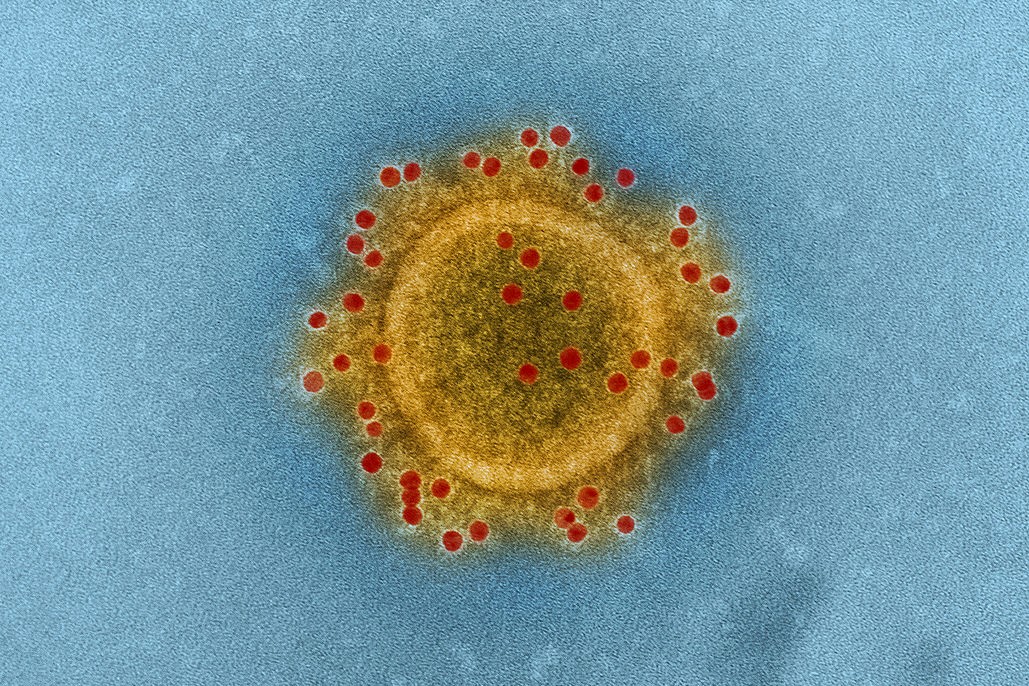

“There is very strong evidence that this virus comes from bats, if not immediately, then in the very recent past. That is quite different to MERS, where the genetic evidence supports it having its ancestors in bats, but MERS CoV having circulated in camels for some time prior to human infection. There were some exciting headlines about snakes being an intermediate host transmitting the Wuhan virus to people, but that analysis had some issues. It may be that there is another intermediate host, like civets in the meat markets may have been for SARS, but the genetic evidence suggests the viruses have not circulated in these species for very long, if at all, because this virus in people is so closely related to ones discovered in Chinese bats.”

What are the circumstances under which a virus can cross over from animals to humans? Is it a random mutation?

“The answer really depends on the virus. For example, for viruses like rabies no mutations are required, but the transmission depends on the infected animal biting an unvaccinated person. However, for some viruses, they may require some specific mutations before they can infect people. For example, there are close relatives to this and SARS like coronaviruses that seem unable to infect human cells in the laboratory and are not reported in people in nature, whereas SARS coronavirus and the new Wuhan coronavirus can. Random mutations can facilitate this prior to infection, and in theory could make those other viruses become infectious to people, or, what can happen is random mutations can facilitate onward transmission in people at some point once the new infection has started to transmit in their new human host populations.”

No conflict of interest declared.

The UK SMC also gathered comments on advice to travellers who have returned from Wuhan in the last 14 days.

Prof Jonathan Ball, Professor of Molecular Virology, University of Nottingham, said:

“Given the scale of the problem in China, it was clear that the UK authorities had to raise their preparedness. Although there are still many questions that remain about how widespread or how this virus is transmitting in China, it is becoming clear that identifying people infected with this novel Coronavirus is challenging – far more so than with either SARS or MERS. Emerging data suggests that the incubation period of the virus can be up to 14 days and during this time infected people might be able to transmit virus without even knowing that they are infected. This is why the self-isolation period is 14 days.

“Some people might argue for more proactive screening of people who have visited China, especially at airports, but this would not identify people infected who are not showing symptoms, especially given the relatively long incubation period. It is possible to test for the presence of virus, in things like sputum or throat swabs, but this would present logistical problems, given the large number of travellers returning from China, especially as the test would need to be performed throughout the danger period.

“The only saving feature in all of this is that the infection appears not to be anywhere near as deadly as SARS or MERS, although it’s this ability to cause asymptomatic or mild disease that is no doubt helping the virus spread.”

Prof Paul Hunter, Professor in Medicine, The Norwich School of Medicine, University of East Anglia, said:

Should British citizens evacuate quarantined areas in Wuhan?

“I do not think this is necessarily an infectious disease issue. The risk of acquiring the infection even in an individual living in Wuhan is still low. The risk of getting severe disease even if infected is also low if someone is below 65 years old and otherwise well. On the other hand, the impact of living in a quarantine environment, miles away from home, can itself be damaging to an individual’s mental health and a source of great anxiety to family members back in the UK. For this latter reason, people may wish to be repatriated.”

Are there any risks of bringing these individuals back to the UK having been in the quarantined areas?

“Given the number of cases reported so far and the total population of the affected cities the probability of any given individual expat being infected on the return home is very low. However, the risk that one or more returnees will be infected with the virus increases the more people are repatriated. So repatriation would carry a small increased risk of importing the infection into the UK but this is unlikely to be great when compared to the risk from all other travelers.

“As reiterated by the World Health Organization today in its live web broadcast the main risk of spreading the infection is still from people who are symptomatic. Given the current size of the outbreak it is quite likely that we will see cases in people coming to our shores whether or not we undertake a mass repatriation. Any risks to people in the UK whether from a repatriation of expats or in other travellers are controlled in exactly the same way. The latest advice from the Department of Health to self-isolate for 14 days after returning and contact NHS 111 if they develop fever, cough and or difficulty in breathing means any risk to others should be minimal.”