People who become infected with COVID-19 have to fight the disease off with their own immune system.

However once the virus has been booted out, it’s hoped people will gain a natural immunity, like those infected with influenza do. Antibody tests are one way to check if someone has this natural immunity, and so the UK has ordered 3.5 million of of them.

The SMC asked experts to comment on COVID-19 immunity issues relating to:

- The immune system and antibody testing

- Sleep (and lack of)

- How to keep a healthy diet

- The UK‘s testing

Associate Professor Helen Petousis-Harris, vaccinologist, University of Auckland, comments:

“To know for sure that having COVID-19 makes people immune to getting reinfected we need to see if those who have recovered get it again. So far there is no good data that this happens, although there can also be exceptions.

“The general thinking is that protection for at least a few years is likely, based on what we know about other coronaviruses. With the common human coronaviruses that cause colds we know that people make immune responses and have antibodies, but after a few years they can get reinfected. We do not know if this is the case with SARS and MERS.

“Assuming people become immune for a while, there is no way to know how long the protection will last, but I imagine it will be at the very least a few years.

“An antibody test will undoubtedly be very useful for indicating if someone has been infected. It won’t tell you for sure if the person is protected because we will not know what correlates with being protected for a while, if ever. However, if we become confident that recovered people are immune to reinfection this will be very useful indeed.

“If someone gets infected the best defence they have is their immune system. There are some scientifically proven ways to optimise the function of the immune system. Those backed by really good research are: Eating as well as possible; getting a bit of exercise (not ultra marathons); and the value of sleep on the performance of the immune system cannot be understated.

“Also, as we know, over time stress can have a negative impact on immunity. During this very stressful time we need to value the importance of looking after our physical and mental health. Spending a fortune on vitamins and potions is unlikely to be helpful.”

No conflict of interest.

Dr Nikki Moreland, Senior Lecturer in Immunology, University of Auckland, comments:

“What normally happens after a viral infection is that your immune system develops an early response, this includes IgM antibodies. In the later stage of infection you get a more mature response, this includes IgG antibodies. These IgG antibodies generally give people longer term protection to a virus.

“There are two different ways that scientists are approaching antibody tests for COVID-19. The first way is the traditional lab-based antibody test from a blood sample, which gives information on the level and type of COVID-19 antibodies someone has in their blood. These tests need to be run in a laboratory and provide doctors and scientists important data to understand that immune response to COVID-19. The other way that scientists are looking to develop antibody tests are quick point-of-care tests. These are based on little lateral flow devices, like a pregnancy dipstick test. You put a finger prick of blood on a wick and within a few minutes you have a quick ‘yes or no’ answer as to whether someone has antibodies to COVID-19.

“The quick tests are receiving a lot of media attention at the moment, with many groups racing to develop them. They would be good for testing out in the community, and also for frontline healthcare workers, but we also need data on the level and types of antibodies people have – so we can understand the long-term immune response – and for this we need the more traditional lab-based tests.

“A lot of people are getting the virus and recovering, and when scientists have looked in their blood, they’ve seen traditional signs of a mature immune response – good levels of IgG antibodies, and evidence that immune cells have activated and responded to the virus. But there is still not enough research published for us to have a clear understanding idea of the immune response to COVID-19.

“In terms of ensuring that you’re going to have a robust immune response – a good healthy diet, getting rest, and generally looking after your body as best you can. All of these things help.”

No conflict of interest.

Dr. John Taylor, Senior Lecturer in Virology, School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland, comments:

“A recent study conducted in China reports that monkeys infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, are protected from symptoms when infected a second time a month later. Not only were there no symptoms following the second exposure, researchers couldn’t detect any virus in the re-infected animals, suggesting they were unable to spread infection.

“This was a small study. Only four animals were infected and only two later re-infected but it does support the pattern of acquired immunity generally seen in humans after virus infection. This immunity depends mostly on the production of antibodies, and in the study all of the monkeys had antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in their blood following the initial infection.

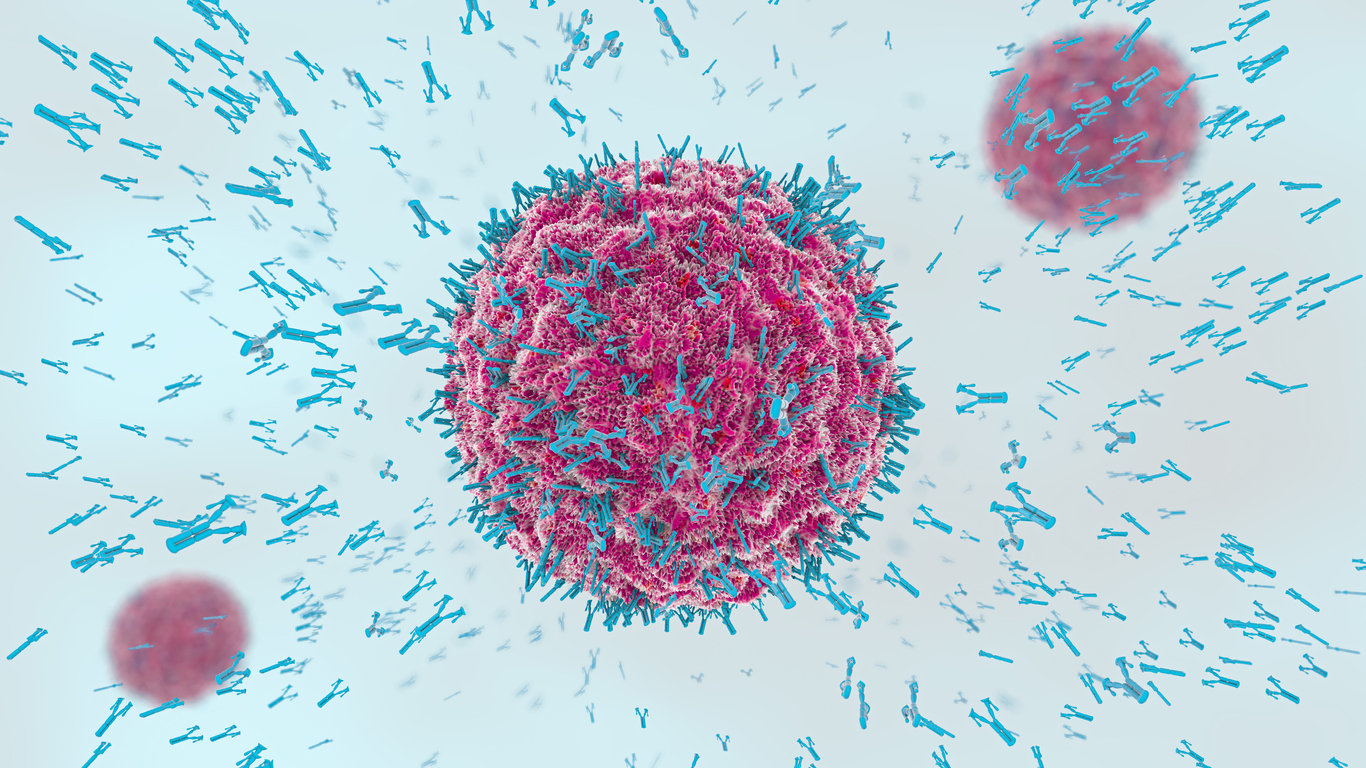

“Antibodies are proteins secreted by B-cells, a type of white blood cell. A process called genetic recombination during B-cell development creates a vast repertoire of different antibodies, each one with a precise specificity for a different antigen. Viruses present hundreds of different antigens to the immune system so that when we become infected with a virus like SARS-CoV-2, hundreds of different antibodies build-up in the blood of an infected person, usually peaking 2-3 weeks after infection. Some of these antibodies are more important than others in ending the infection. Neutralising antibodies bind to the virus and block its attachment to the cells in which it needs to replicate, putting the brakes on further spread of virus. We can think of antibodies as the body’s own self-made antiviral drug.

“This has caused some countries to consider using the blood of people who have recovered from COVID-19 as a possible treatment of patients currently infected. Using the blood of people who have recovered from a disease to treat people who still have it, is in fact a technique that has been known for a hundred years. More recently the approach has been used to treat patients with SARS or Ebola with some success. Drug companies are now screening the blood of patients who have recovered from COVID-19, looking for the most potent neutralizing antibodies to develop as therapeutic weapons to fight the virus.

“Antibodies have another use in controlling the current pandemic. Tests to detect the presence of antibodies in blood – called serology tests – can reveal if a person has been exposed to the virus in the past, even if they were not tested for the presence of the virus at the time, or have experienced no symptoms.

“The good news about serology tests is that they give rapid results, usually in less than an hour, and require only a pinprick of blood. The UK government has reportedly placed an order for 3.5 million serology test kits and intends to offer the test to frontline doctors and nurses, allowing them to see if they have already been exposed to the virus and are therefore immune.

“Some caution needs to be exercised here though: it may take some time to confirm that a positive serology test indicates complete protection against reinfection. The amount of neutralising antibody in different people varies after other types of infection or after vaccination and we cannot repeat the monkey experiment in humans to prove protection.

“However, the test could give some reassurance to healthcare workers at heightened risk of infection and who fear spreading the virus to their families. It is also critical that any test is carefully validated to ensure that a positive result comes from SARS-CoV-2 and not a previous exposure to the related human coronaviruses that cause common colds.

“A further complication is whether any pre-existing auto-immune conditions that can result in unusual antibody production and are found predominantly in elderly people, such as rheumatoid arthritis, interfere with the test.

“Yet another question is which of the many different antibodies an infected person makes against the virus will the tests detect? Some of the serology screening tests available measure antibodies against the spike protein of the virus. These antibodies are most likely to be neutralizing and offer protection from reinfection because the spike is the part of the virus that attaches to cells.

“Some tests developed Singapore, the Netherlands and the US have already reported on the required degree of specificity, and researchers in New Zealand are currently working on replicating some of these tests. If successful we could soon be able to roll out serology testing to target groups like healthcare professionals or other essential service workers before expanding into the general population to give a new and improved measure of the virus spread and immunity among New Zealanders.”

No conflict of interest declared.

Dr Rosie Gibson, Research Officer at the Sleep/Wake Research Centre, Massey University, comments:

“Sleep provides a foundation for our physical and mental wellbeing. It also boosts the effectiveness of special cells involved with the body’s immune response. The Covid-19 pandemic has dealt a time of acute stressors and rapid sociological changes. Losing sleep over this situation is to be expected.

“But, as we acclimatise to this period of lockdown, it is important to consider sleep as a natural tonic. Sleep will help us to psychologically adapt to our changing circumstances while also defending us against disease and supporting healing.

“Achieving sufficient hours of sleep is important but so is the timing and regularity of sleep. Maintaining consistent routines may become more challenging whilst in lockdown. Our internal body clock and sleep/wake cycle is synchronised via exposures to external time cues. Light, physical activity and social engagement are key so try to maintain regular exposures during lockdown. Consider scheduling morning tea breaks in natural light, working from the garden or by a window, and avoid using brightly lit devices too much at night. Taking routine solitary exercise outside is recommended, timing this when we would typically commute or socialise will help.

“Being physically separated does not mean sacrificing all social stimulation. Try to schedule family meal or game times (in person or online), virtual meeting dates with colleagues and phone conversations with family and friends. Creating and maintaining consistent exposures to these time cues will not only stimulate good sleep but will support overall wellbeing and help keep us connected.

“Blending work with family environments can impact sleep, mental health, and productivity. This will be exacerbated in this time of uncertainty. If possible, keep the bed and bedroom predominantly for sleep. Exposing ourselves to the news or using brightly lit devices the hour or two before bed can prevent relaxation and destabilise the sleep rhythms. Make the time to wind-down and talk through or write down concerns before attempting sleep. If you struggle to get to sleep or wake up in the night and cannot get back to sleep, do something calming in another space and return to bed when tired again.

“Try to maintain routine rise and work/activity times. Get dressed for the day and avoid the temptation to work from bed. If consuming alcohol or caffeine consider how and when you do as this can reduce the efficiency of sleep as well as contribute to anxiety. Sleep loss during this time will be common, be aware of how you feel in the day and schedule a nap if needed.

“During this lockdown period we must appreciate the sleep schedules of others. For example, older people are often synchronised to sleeping earlier and are more easily woken at night. Support one another, especially the older and vulnerable, to maintain healthy sleeping practices. This will strengthen our immune systems and support wellbeing during this extraordinary time.

“All that said, I am writing this in the early hours of the morning, still in PJs while the children watch TV instead of their school routine. There are gaps between health advice and reality and people shouldn’t become overly stressed with guidance, particularly in this rapidly changing time.”

No conflict of interest.

Emeritus Professor Elaine Rush, Professor of Nutrition, Auckland University of Technology, comments:

“Worldwide experts agree that a diet of a combination of wholesome, relatively unprocessed foods – mainly plants – is best for health, immunity and longevity. In addition physical movement such as walking and the fellowship of sharing, in your bubble and virtually with others, are vital. Three Fs: food, feet and fellowship. These all help the immune system to do its work.”The overall quality of a diet is judged by its diversity, whole food characteristics and quantities of each food. In the shopping trolley (or from the garden and pantry) and on the plates a general rule is that almost half the volume (not weight) should be vegetables that grow above the ground, these are coloured and in particular dark green leafy vegetables such as spinach, silverbeet, Chinese cabbage, and pūwhā, which are good sources of vitamin A and antioxidants which support the immune system. With the addition of fruit including citrus or kiwi for vitamin C, half the trolley is completed. The next quarter is good sources of protein that may include milk, beans, eggs, milk and cheese, and the final quarter starchy staples such as potatoes, rice and pasta.

“A supply of vegetables and fruit can be stored as frozen or canned which are just as good nutritionally. In addition ingredients that make food tasty, garlic, spices and herbs, are important. Food must be enjoyed and celebrated.

“The challenge is to ensure that good food reaches those most in need, that in a household there is enough money for food, and that food for health and recovery are a priority.”

No conflict of interest.

Professor David Wraith, Professor of Immunology and Director of the Institute of Immunology and Immunotherapy at the University of Birmingham, comments:

“Various companies have recently reported development of tests for anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, including the finger-prick assay that is to be used in the UK. At present these are not extensively tested but will give a +/- readout of immune status.

“Scientific publications released this week, show that it will be possible to establish a more accurate way to detect anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. This is important because antibody tests will give us a safe way to judge whether or not someone is infected since we now know that antibodies appear shortly after symptoms.

“This will allow us to distinguish those people who have had SARS-CoV-2 versus the many other bugs that are flying around at this time of year and can give similar symptoms. This is a key point: the information provided will tell us who among individuals in our [health service] and other essential workforces are immune to the virus and, therefore, safe to return to their vital work.

“For many people, it is difficult to know whether they have had a cold, flu or SARS-CoV-2: if these individuals don’t need to self-isolate for long periods then they can return to the critical workforce confident that they have built up immunity to the infection. However, a more sophisticated test than those currently available is required to assess the type and strength of immunity that correlates with effective and long-term protection.

“Furthermore, when a vaccine for this virus comes along, we must have a validated and quantitative assay for us to test the vaccine. In the meantime, we need a validated test to identify individuals who make strong immune responses who could donate antibodies to those who are severely affected. We could also isolate antibody genes from such strong responders to reproduce their antibodies in the laboratory and use them as drugs for immunotherapy of critically ill patients.

“Much work still needs to be done to optimise the sensitivity, validate the assay and put this onto a platform that can be used readily. This work is critical and urgent and Universities, particularly UK universities, will be key. We in Birmingham have the expertise required for this and will work with industry to do all that is required to produce an effective test.”

No conflict of interest declared.

Professor Wraith’s comments come via the UK Science Media Centre.