The SMC led an online media briefing with an author of a study showing how news reports are linked to the nocebo effect in antidepressants.

Professor Keith Petrie, University of Auckland

The full briefing and excerpted transcript are available here.

What is the nocebo effect?

“Probably everyone’s heard of the placebo effect, which has a great deal of research completed on it. That’s when people’s positive expectations – or anticipations of a positive effect – from a treatment causes benefits, rather than the treatment itself.

“The important thing to say about the placebo effect is that all treatments in medicine cash in on it. It adds to the overall effect of a treatment. All treatments are partly made up of the benefits from placebo expectations, and ideally from some benefits of the treatment itself. But some treatments that can be completely inert or useless can benefit people, just from the placebo effect.

“The nocebo effect is the ugly sister, if you like, of the placebo effect. It’s attracted less interest but it’s probably, in terms of medicine, more important – because it causes a lot of problems for treatments in clinical situations. People tend to come off drugs earlier because of the nocebo effect. They don’t persist with treatment, and it causes a great deal of distress.

“The nocebo effect is the adverse effects, due to people’s negative expectations from a treatment.

“Originally it was applied to an inert treatment, like people getting side effects in the placebo arm of clinical trials. But more recently the concept broadened to include side effects that are not due to the active ingredients of a treatment itself. It’s also widened to include aspects of technology as well. New technology particularly attracts nocebo effects – things like wifi, wind turbines, 5G.”

Are there any populations that are particularly susceptible to the nocebo effect?

“Studies that we’ve done have shown there are higher rates, particularly after switches to generic drugs. People who are older, and women, tend to have higher rates of nocebo effect reporting. That may be due to the fact that women report more symptoms, so there are more symptoms to misattribute to a treatment.”

Could you explain your recent research?

“The study that we’re talking about today is essentially a follow on from an earlier study we’d done on the effect of print news stories following a switch to a generic medicine.

“We were interested to look at the processes involved in the nocebo effect, and particularly the role of social modeling, and how people report symptoms because they see other people report symptoms.

“We’re also interested in this whole process of branding. Generic medicine is an interesting one for the nocebo effect, because the branding has been removed from the medicine. As human beings we rely on cues like price to help us determine quality, and we do this a lot of the time subconsciously. When people are given a generic medicine, there tends to be a lot of negative perceptions about generics being less effective, or cheaper versions of branded medication.

“What we did look at was after a switch from a branded version of venlafaxine to a generic, some patients started reporting side effects.

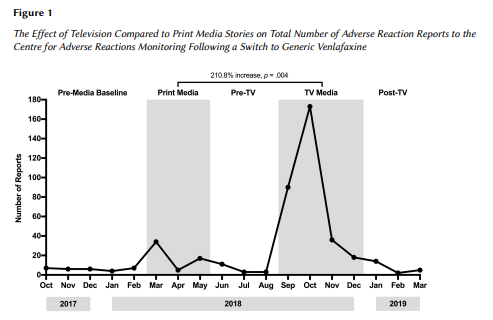

“This was picked up initially by the print media, and that caused an increase in side effect reporting, which we thought at that time was quite big. Several months passed, and the story resurfaced again, and it was picked up by television media. That allowed us to look at the differential effect of print versus television on side effects, or nocebo responses.

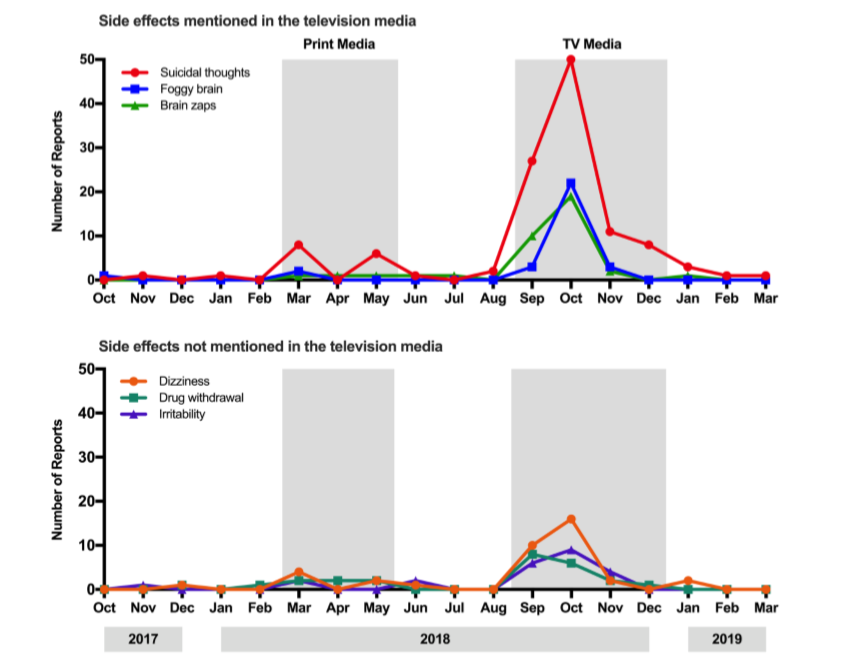

“What we found in the study was that TV caused a much greater effect than newspaper stories. We also found the specific side effects mentioned in the TV reports, were the ones that were mentioned in the month after in the reports to the Centre for Adverse Reactions Monitoring (CARM).”

Could you talk about the side effect reporting increases and the symptoms you found that aligned with news reporting?

“Overall we found that television stories increased side effect reporting by around 200% more than the print articles. The more public health-relevant fact was the increase in specific symptoms, in particular suicidal thoughts. When those were mentioned [in the media], they went from a very low base rate to a rapid increase. That’s more of a public health worry, that people believing they were going to get stronger suicidal thoughts on this new medication. That mainly came from the conversations with patients that were shown on the television reports.

“Not only can side effects increase, but sometimes when you’re dealing with psychiatric conditions, suicidal thoughts may cause an increase in suicidal behavior. We haven’t examined that yet but we may do at some point.”

What’s the key takeaway from this study?

“TV is much more powerful at creating nocebo effects. The reason why, we suspect, is because people identify with the patients in the stories – very similar to the effect of media on suicidal behavior.

“How do we know it wasn’t actually the drug that caused this effect? You can see that the side-effect reporting was actually quite low before the media reporting and it dropped away again afterwards. If there’s something wrong with the drug, you’d see generally a different pattern and an increase in reports over time.

“The other thing that discounts the idea that the drug was causing the problems is the specific symptoms that were mentioned in the bulletins, compared to symptoms that weren’t mentioned in the bulletins. We looked at that and found the symptoms mentioned in the bulletins tended to be the ones that were reported afterwards. There were some that were only mentioned in the bulletins – one particular one called ‘brain zaps’ wasn’t mentioned before, and only appeared in the [symptom] reports after the TV report.”

“You can see [in the graph] that after the news reports there’s a dropping down, pretty much to baseline afterwards, which you can see occured by February.

“The key things are how rapidly symptom reports increase after the news reporting, and if you look at reporting levels of symptoms that weren’t in the news bulletins. That gives you added confidence that it’s due to the TV news.”

Patients sometimes think that this means the symptoms are ‘in their heads’. But can’t these symptoms be clinically diagnosed?

“Most of the symptoms we’re talking about are ‘in our heads’. And symptoms are actually quite common. If you go out and knock on people’s doors like we have done, and ask them how many symptoms they’ve had, you’ll find a median number of about five symptoms in the past week.

“Having those symptoms is quite normal. Symptoms aren’t generally a sign of illness. People have back pain, headaches, muscle aches, dizziness, you name it. So there’s a big sea of things people can draw on to misattribute to whatever treatment they’re having.

“Placebo and nocebo responses tend to be more subjective complaints. That’s why the placebo effect won’t cure cancer but it can make your heart race or have your breathing constricted if you think you’ve had a drug that will do that.

“When we give people a [placebo] which they expect to slow their heart rate, generally their heart rate slows.”

Can the nocebo effect explain the lamotrigine epilepsy drug switch linked to multiple deaths?

“One of the important things about the lamotrigine switch which I think maybe wasn’t picked up that well in the media, is that there are a number of deaths that occur to people with epilepsy that are on medication. I’m not quite sure of the figures – let’s say it’s 50 people a year who are on the existing drug will die. When they’re switched to a new drug, that baseline number of deaths is not going to change, just because they’re on a new drug. So you are going to see deaths on the new drug as well as on the old drug.

“[But the nocebo effect wouldn’t play a role] in deaths, I wouldn’t think.”

Should patients be concerned when there’s a drug brand switch?

“My understanding is there’s quite a process that goes on before the switches are made. A lot of the drugs that are switched have been used in other countries for a number of years. Sometimes I think the public doesn’t get good information about that. I think one of the problems we’ve got in our system is that Pharmac can’t contact patients directly, so I think there could be better ways to communicate with patients around drug switches.”

What would your advice be for reporters to avoid creating a nocebo effect?

“One of the things I think’s important is just reporting the overall rate compared to how many people are on the medicine. Venlafaxine is probably a good example of that – I think there are 45,000 people on the drug. The reporting rate of adverse events – even if we took each adverse event as a separate case – would still be only one per cent of people who are on the drug, and that’s probably an overestimation. The reporting on television has given the impression that it’s much more widespread than that.

“I think just a general awareness of the fact that this type of news reporting will increase overall symptom reporting. It becomes a bit of a self-fulfilling prophecy in some ways. You can interview patients that are having problems, put that in a bulletin, and you’ll receive a lot more symptom reports soon afterwards. That in itself becomes another news report, and on it goes.

“Explaining to people about the nocebo effect, because a lot of people don’t know about it. Just explaining that it’s a natural process that happens all the time. I think once people hear about it, that tends to defuse this process. There’s certainly evidence for that from some of the studies that we’ve done.”

Conflict of interest statement: Keith Petrie has previously received funding from Pharmac, but not for this current research.