A series of violent eruptions from submarine volcano Hunga Tonga Hunga Ha’apai triggered towering 20km-high ash plumes and destructive tsunami waves in Tonga.

The tsunami has reached as far as Alaska, Japan, and South America. A New Zealand Defence Force plane left this morning for a reconnaissance flight to assess the damage.

The SMC asked experts to comment.

Dr Emily Lane, NIWA Taihoro Nukurangi, comments:

“This is a very significant eruption – the shock wave from it is clearly visible in satellite imagery and there are reports of the eruption being heard at least as far away as New Zealand.

“The tsunami from the eruption has reached over 2,500 km being recorded on gauges over all of Aotearoa.

“Tsunamis generated by volcanos are not as common as tsunamis generated by underwater earthquakes. Only about 5% of historical tsunamis have been caused by volcanic eruptions.

“There are lots of different ways that volcanos can cause tsunamis. These include the explosion from an underwater eruption itself, pyroclastic density currents, flank collapse (when part of a volcano collapses into the sea – this is what caused the tsunami in Indonesia from Anak Krakatau in 2018), caldera collapse (where the sea floor collapses because the magma from the caldera has exploded out) etc.

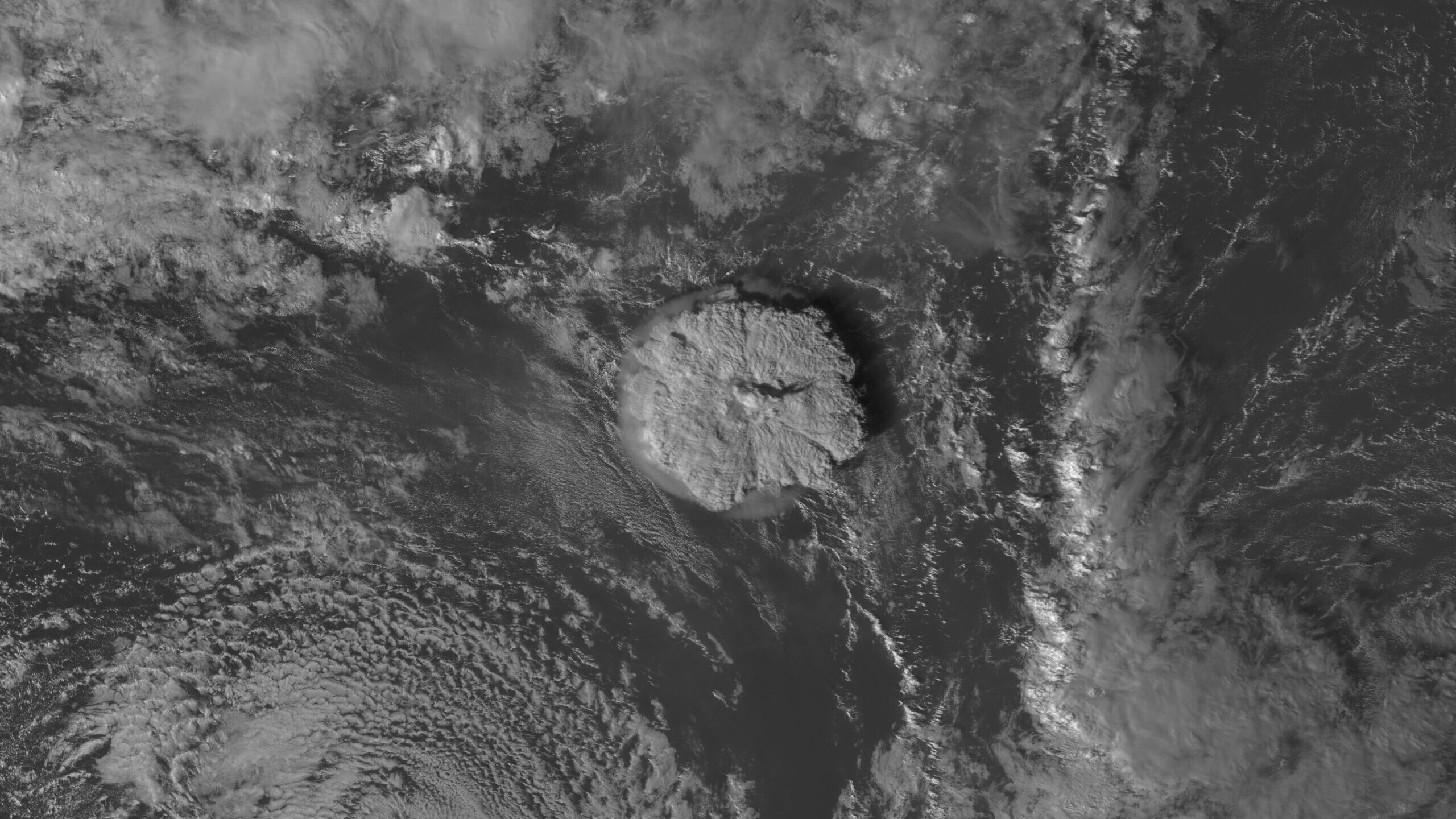

“Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Ha-apai had a previous smaller eruption late 2014-early 2015 which built up the crater to above the water surface as you can see from these two aerial images taken from Google Earth. When we see what is left of the island after this eruption is over we can start to put together the pieces of what happened.”

Pre 2014/2015 eruption (Feb 2014)

Post 2014/2015 eruption (May 2016)

No conflicts of interest declared.

Professor Shane Cronin, School of Environment, University of Auckland, comments:

“Based analysis of volcanic ash layers within lake and swamp cores throughout Tonga my colleagues and I have found that ~25 major eruptions that have covered the inhabited islands of Tonga with volcanic ash over the last 6500 years. These have been from volcanoes such as Hunga (Hunga Tonga Hunga Haa’apai) as well as Tofua and Fonualei.

“Research work we have completed on Hunga volcano, shows that there have been many historical eruptions (most recently in 2009 and 2014-15). These historical events are too small to leave any significant ash on the main islands and generally do not cause regional issues such as tsunami. They mainly involve the explosive interaction of small amounts of basaltic andesite magma with sea water.

“We have also found evidence for two major eruptions at Hunga, with radiocarbon dating suggesting one at ~AD1100 and another at ~AD200. This, along with other data from the volcanic ash records suggests a recurrence interval of ~900 to 1000 years for very large eruptions at the volcano.

“The current eruption seems to be one of these large events which fits with the timing since the last of these in ~AD1100.

“The past large Hunga eruptions were comparable to the scale that we have seen in the 15 January 2022 event or larger. Based on these past events, tephra (ash) falls of up to 20 cm thick can be expected on Tongatapu and the Ha’apai group of islands. Geological deposits on Hunga Ha’apai of the AD1000 and AD200 eruptions suggest that there were many eruptive phases during each of the major eruption episodes.

“This suggests that the current eruption episode could last several weeks or months and that further similar sized eruptions to the 15 January 2022 event are possible.

“The very large eruption of 15 January 2022 is remarkable due to the rapid lateral expansion of the eruption cloud (seen in satellite images), coupled with tsunami and atmospheric shockwaves. This suggests the eruption of large volumes of gas-charged magma at Hunga volcano. Notably all of the historical smaller eruptions seen, such as 2014-15, were produced from small vents that are within or on the edge of a large ‘caldera’ (sunken volcano). The caldera at Hunga is ~5 km in diameter. This caldera is formed by the collapse of the top of the volcano during very large events.

“The 15 January 2022 eruption is so large that it is likely to be an event that alters the caldera. The caldera rim is near sea level, but the centre of it was ~200 m deep during our surveys in 2016. Further eruptions from this caldera during this episode could generate new tsunami and widespread ashfall, especially if there caldera has further collapses or landslides.

“The magma type erupted at Hunga volcano is an intermediate composition – andesite to dacite – similar to that Ruapehu volcano. Based on the past compositions, the magma is not especially rich in volatiles such as sulphur or fluorine. Hence this volcanic ash is not especially toxic, but notably all volcanic ash can produce acid rain and acid leachates.

“The eruption is likely to result in significant ash fall (cm to ten cm) in Tongatapu as well as the Ha’apai group of islands. Help will be needed to restore drinking water supplies. People of Tonga must also remain vigilant for further eruptions and especially tsunami with short notice and should avoid low lying areas.”

Conflict of interest statement: No conflict of interest. I work for the University of Auckland. I have received funding from the Faculty of Science to work on Hunga volcano.

Senior Lecturer Marco Brenna, School of Geology, University of Otago, comments:

“The satellite images appear to show a very significant eruption, much larger than what Hunga did in recent history. The volcano erupted several times over the past century (1912, 1937, 1988, 2009, 2014). Little is known of the early 1900s ones, but of the last three, the erupted volumes appeared to be increasing. The recent eruption begun not unlike its predecessors in December. However, over the past few days the volcano generated much larger explosive events. It is too early to say at this stage how the situation might evolve. I am not aware of direct observation of today’s event as yet.

“From satellite imagery the eruption plume (cloud) spread over a vast area, including the inhabited islands of Tonga. There will therefore likely be ash fallout, which will impact health for locals, such as contaminating drinking water and causing respiratory issues. Depending on how the eruption proceeds there could also be further tsunamis.

“As far as I am aware there is no active monitoring of Hunga Volcano. That was certainly the case in 2015 when we visited the site, and I have not read of any reports citing monitoring signals. That is in stark contrast with New Zealand volcanoes, which have a wide array of monitoring equipment run by GNS Science.

“Hunga volcano is part of the string of volcanoes forming the Tonga Arc, formed by the subducting Pacific tectonic plate beneath the Indo-Australian tectonic plate. Its feature is a summit caldera formed during large eruptions (larger than what seen thus far) around 900 years ago, so it is basically a truncated cone, with the 1988-2015, as well as the initiation of this eruption last December forming small pyroclastic cones around the caldera rim. There is a magma reservoir at some 5-6 km depth that has been feeding the previous eruptions (this model we present in a scientific paper soon to be published), and it is likely that the ongoing event is being fed by the same reservoir. There is therefore ready availability of magma, but how/if this will feed an eruption is yet to be seen.”

No conflicts of interest declared.