Brain scans of patients infected with Covid-19 show changes in regions that affect memory and smell, and increased cognitive decline.

In one of the biggest-yet COVID-19 brain imaging studies, researchers looked at scans from 785 people aged 51 to 81 in the UK – before and after mostly mild COVID-19 infection. The authors say the documented effects were still seen after excluding the 15 people who had been hospitalised with COVID-19, implying even mild illness may have consequences for the brain.

The SMC asked experts to comment on the research. Our colleagues at the Australian Science Media Centre also gathered expert reaction to this study.

Professor Maurice Curtis, Head of Department, Anatomy and Medical Imaging, University of Auckland, comments:

“This is carefully performed work that utilises the data from about 780 people who had had an MRI brain scan as part of a bio-banking initiative prior to the pandemic who have then had their brain imaged again after they have had Covid-19. In addition a similar age group of participants have been scanned with the same time interval that had not had Covid-19, as a comparison.

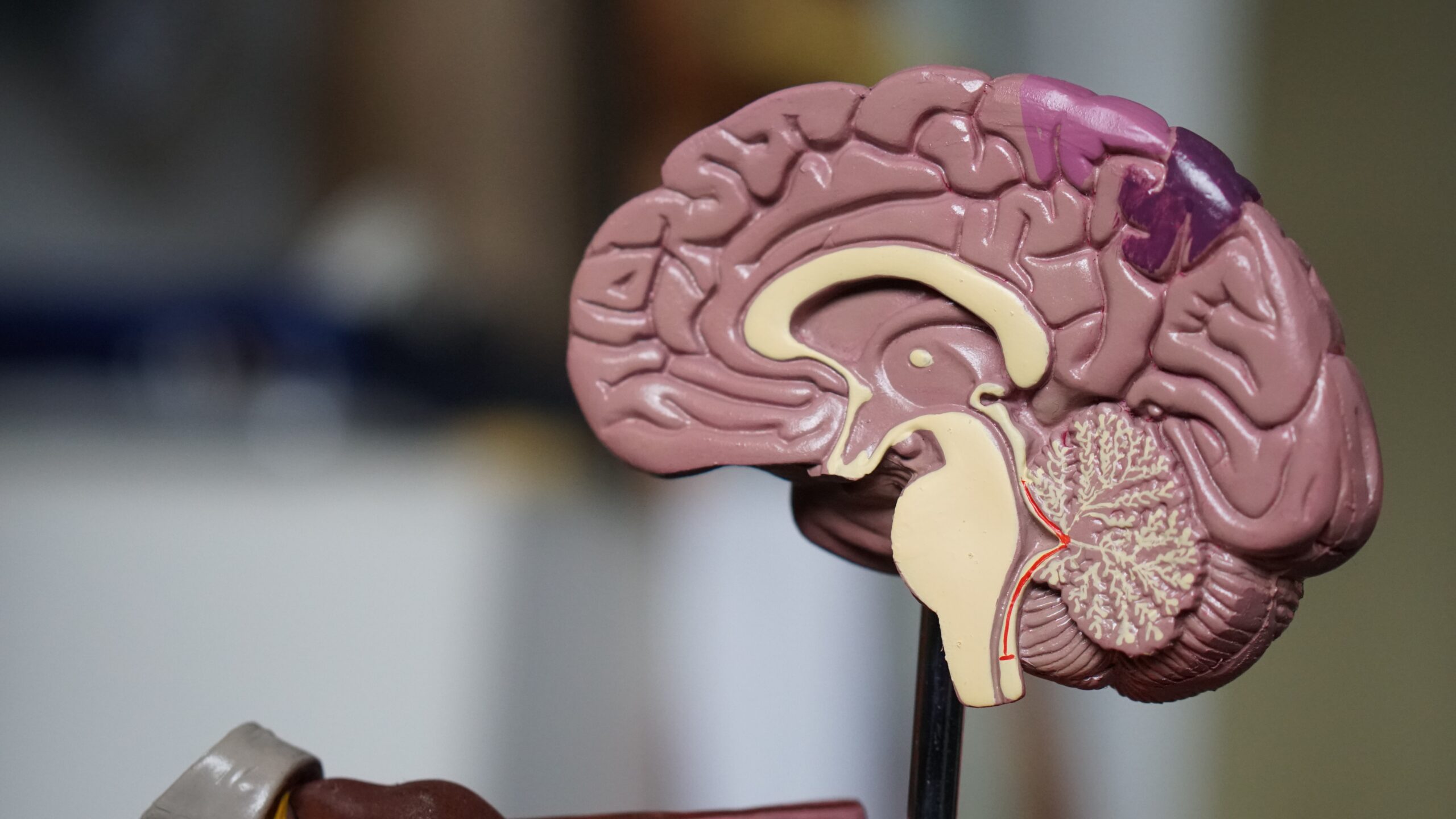

“The findings demonstrate that the brain pathways that relate to the sense of smell and the pathways that relate to memory formation and recall have shrunk in those that had had Covid-19. The shrinkage or loss of brain volume was significant and exceeded a 6 per cent difference on average.

“Furthermore, those who demonstrated this shrinkage, performed significantly worse on executive function, visual searching and mental flexibility tests (Trails tests). We know that loss of the sense of smell very early on in Covid-19 is a key sign of infection and some people never get their sense of smell back. The smell pathway and the memory pathway in the brain are connected and these are the same pathways affected in some dementias including Alzheimer’s disease.

“From the available data the researchers also conclude that Covid-19 causes the shrinkage whereas being infected with the seasonal flu did not cause brain shrinkage.

“This study demonstrates that there is a long-term consequence to getting Covid-19 and it highlights the importance of taking all measures possible to reduce Covid-19’s impact on the body and especially the brain.”

No conflict of interest.

Dr Indranil Basak, Research Fellow, Neurodegenerative and Lysosomal Diseases Laboratory, University of Otago, comments:

“This is a well performed longitudinal study, the results look very interesting, but worrying as well. It is a very good example of what Covid-19 can do to the human system long term.

“This study looked at the different brain regions and changes in the brain size. Our research team is looking at the molecular and cellular level – what’s going on inside the brain cells when they are exposed to the virus. The results from our experiments will help us understand what is happening inside the cells, which could be leading to the changes in the brain that are highlighted in this study.

“Our preliminary data shows some infection in brain cells, including neurons. However, we still don’t know if the virus can enter these cells after crossing the blood-brain barrier, or if the symptoms we’re seeing inside the cells are because of some other reason. For example, there is an immune response when the virus is infecting our bodies, which could be causing secondary effects that affect the brain cells as well.

“There are definitely several cases where patients infected with the virus started getting neurological symptoms like dizziness, disturbed consciousness, headache, loss of smell and taste, seizure, encephalitis and there have been links with Parkinson’s disease.

“From this research and our own, it is clear there is an effect on the brain from Covid-19 infection, and this could lead to some Long Covid effects. We still don’t know how to treat this, because no one has looked at it yet. But we do know that the virus directly, or indirectly, can affect the human brain.”

Conflict of interest statement: Our study was funded by the Otago Medical Research Foundation and the Brain Health Research Centre, both at the University of Otago and Brain Research New Zealand.