Warm oceans, warm air, La Niña conditions, and a changing climate have made for a summer of perfect storms – with Cyclone Gabrielle no exception.

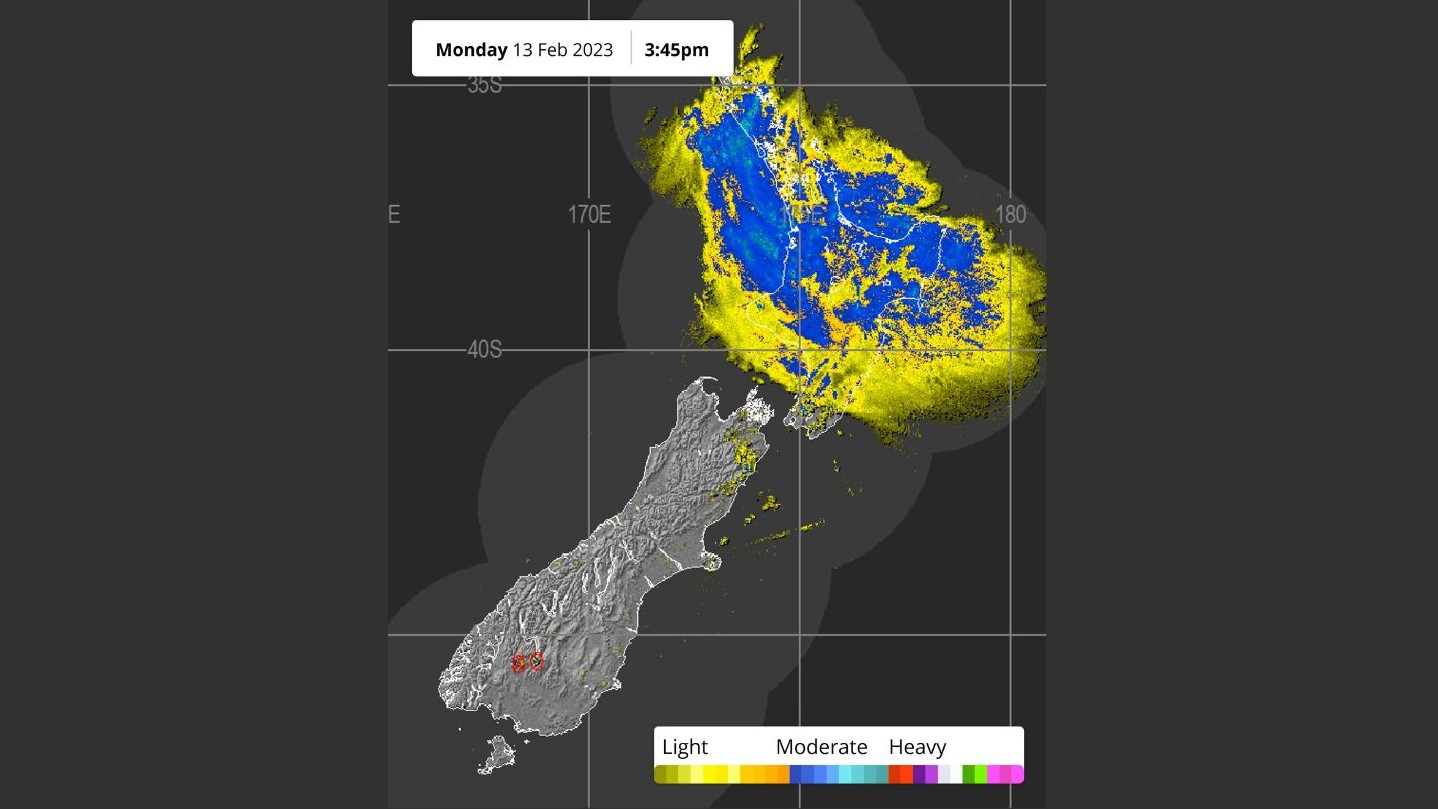

The extreme low pressure system is expected to continue to affect the North Island until at least Tuesday.

The SMC asked experts to comment on why we’re seeing such a strong cyclone hit New Zealand today.

Dr Dáithí Stone, climate scientist, NIWA, comments:

“This summer just keeps on giving to the top of the North Island. Each summer, Northland and Auckland are usually on the verge of drought, with a pretty severe one experienced just three years ago. Not this summer. The most recent of a slew of big dumps of rain is the current landfall or near-landfall of ex-Tropical Cyclone Gabrielle. How does Gabrielle fit into the soggy picture of this summer?

“Tropical cyclones feed off of the energy provided by hot ocean waters. This year has followed recent summers in having unusually warm water in the Tasman Sea and around Aotearoa. This warm water is partly an effect of the warm “La Niña” waters spanning the western tropical Pacific and partly some local ocean activities happening in the Tasman Sea, but the ongoing warming trend from human-induced climate change is playing a big role too.

“While the seas around Aotearoa are still not hot enough to sustain a tropical cyclone, tropical cyclones like Gabrielle can maintain themselves much closer to us than before and are not disrupted so much by cooler seas that are no longer there. La Niña events also change the winds, bring more hot and wet air from the tropics our way. Finally, the warmer air of a warming world can hold all of that moisture until it meets the mountains of Aotearoa. In that sense Gabrielle is very much part of the story this summer of a warm nearby ocean using a warm atmosphere to pump rain onto Aotearoa. It is also part of the global story of tropical cyclones becoming more intense under human-induced climate change.

“There is more to the story though. Even with the warmer waters close to Aotearoa, it is unusual for tropical cyclones to reach this far south. Climate researchers have not been able to figure out yet if La Niña events will change under human-induced warming. Globally, it seems that climate change reduces the total number of tropical cyclones slightly, even while making them stronger. So is Gabrielle’s track toward us a fluke then, against the grain of climate change, or does it portend the future? We do not really know at the moment, but NIWA, the MBIE Endeavour Whakahura project, and colleagues in Australia are developing techniques that we hope will help us answer that question very soon.”

No conflict of interest declared.

Dr Joao de Souza, Director, Moana Project; and Science Lead and Research & Development Manager, MetOcean Solutions, comments:

“The waters in the Tasman Sea and around New Zealand have been unusually warm. The rate of warming has been above the global average since 2012-2013, with the last 2 years presenting record-breaking ocean temperatures leading to unprecedented marine heat waves around Aotearoa. The temperature we observe at a defined moment is a consequence of the compound effect of climate change, long-term ocean processes such as La Nina, and short-term processes such as high-pressure atmospheric systems or tropical cyclones.

“Higher ocean temperatures mean that more heat (energy) is available. All this heat and moisture are transferred to the atmosphere as storms blow and mix the top water layers. This process fuels the tropical cyclones travelling over the warmer-than-normal waters, potentially delaying their fading and increasing coastal precipitation. As the storm passes over New Zealand we see the ocean surface temperatures decrease as a consequence of the energy being drawn and surface waters being mixed with deeper, cooler waters. This is happening right now with Cyclone Gabrielle. Once the cyclone moves away we should see the ocean surface temperatures raise again, responding to the long-term forcings. All this means we have the pre-conditions necessary for the generation of new storms in the Coral Sea and their impact on New Zealand. And this situation is forecasted to prevail at least until April-May.

“In the next decades down to the end of this century, we anticipate that ocean temperatures will steadily climb and extreme events such as marine heat waves and storms will become more common, intense, and long-lasting. The actual trajectory, however, depends on how society will tackle the climate change challenge.”

No conflict of interest declared.

Dr Luke Harrington, Senior Lecturer in Climate Change, University of Waikato, comments:

“This ex-tropical cyclone is quite different to the one which impacted Auckland several weeks ago. The flash flooding over Anniversary Weekend was caused by no more than a few hours of repeated thunderstorms which simply overwhelmed drainage systems. It was short-lived and the spatial footprint was small, but unfortunately it happened to be a direct hit on our largest city.

“This ex-tropical cyclone is more typical of what can occur in the late summer in any year – extreme wind and rain from these systems can impact a much larger swathe of the North Island and persist for several days rather than several hours.

“Large-scale climate drivers (like La Niña) have elevated the risks of such an event happening this summer: in fact, seasonal predictions pointed to elevated chances of multiple TCs occurring in this region of the Pacific as early as October.

“In general, tropical cyclones are expected to become less frequent in a warming world, but the number of events which reach category 4 or 5 tropical cyclones are expected to increase, in part because the speed with which they intensify is also increasing.

“It’s likely that the low pressure centre of the system will be slightly more extreme than what might have been in a world without climate change, with the associated winds therefore likely also slightly stronger – however, there’s uncertainty over the magnitude of this influence at current levels of warming.

“The clearest signal of climate change for ex-tropical cyclones relates to the amount of rain which falls from the system. When analysing the wettest day associated with ex-TC Debbie, which also impacted the northern half of the North Island in 2017, our results found approximately 5-10% more rain fell. This roughly corresponded to a doubling in the frequency of similarly wet events when compared to model simulations of a world without climate change.”

No conflict of interest declared.