A new Department of Conservation report estimates there are approximately 55 Maui’s dolphins left, leading experts to call for better protection for the world’s rarest dolphin.

The DOC report is based on DNA analysis of genetic samples collected from dolphins between February and March in 2010 and 2011. The research team collected samples from a total of 41 different individuals, with some dolphins being sampled more than once – allowing an estimation of the total population.

The DOC report is based on DNA analysis of genetic samples collected from dolphins between February and March in 2010 and 2011. The research team collected samples from a total of 41 different individuals, with some dolphins being sampled more than once – allowing an estimation of the total population.

The study estimates that the current population of Maui’s dolphins over the age of 1 year is 48 to 69 dolphins, with a middle estimate of 55. Based on previous dolphin surveys, the researchers estimate that the population is declining at a rate of 3% per year.

The researchers also noted that two Hector’s dolphins were swimming with Maui’s dolphins and that there was a possibility of interbreeding, which could help the Maiu’s dolphin population by increasing genetic diversity.

A copy of the report and a summary can be found here, and a roundup of media coverage is available here.

In response to the report, the Government has brought forward a review of the Hector’s and Maui’s Threat Management Plan and implemented several interim measures to protect the dolphins, announced in a press release.

In an Auckland University press release, report author Prof Scott Baker said that, “despite low abundance the population has maintained an equal balance of females and males and retained a surprising, albeit low, level of genetic diversity over the years”.

Co-researcher Dr Rochelle Constantine added, “One concern with such a dangerously low number of breeding females has been that the fertility of the population may be compromised, but our work shows that the number of pregnant females is within the expected range, which is encouraging”.

Associate Prof Liz Slooten, Zoology Department, University of Otago, answered the following questions for the Science Media Centre:

How did the population get so low?

“The population has dropped from around 1000 individuals (in 1970) to 111 in 2004, and now apparently even further, due to dolphin deaths in fishing nets (in particular gillnets and trawl nets).

“There are other potential and future threats (including pollution, marine mining and tidal turbines). But the Threat Management Plan, compiled by DOC and Ministry of Fisheries lists fisheries mortality as the number 1 threat. This report was the result of several years of consultation with fishing industry, conservation groups, scientists, iwi and others.”

What safeguards are already in place and what further initiatives should be undertaken to protect the Maui’s dolphin (if any)?

“Currently there is a ban on the use of gillnets between Maunganui Bluffs (near Dargaville) and Pariokariwa Point (north of New Plymouth) out to 7 nautical miles offshore.

The two most important loopholes are:

1. Protection doesn’t go far enough south

2. The harbours are not included

“A research report published by the Ministry of Fisheries (in their own journal) in 2005 shows that the Maui’s dolphin distribution goes much further south than the protected area. Research carried out by Otago University, Auckland University and DOC scientists, and published by the Ministry of Fisheries[1], shows that Maui’s dolphins range at least as far south as Cape Egmont.

“In 2009, a fisherman saw a Maui’s dolphin, well south of the protected area, and filmed it on his cellphone:

“Then there was the dead dolphin off Cape Egmont on 2 January 2012:

“It sounds like the government is now considering closing the loophole at the southern end of the Maui’s dolphin distribution. They have “proposed” banning gillnets south to Hawera, out to 4 nautical miles offshore, but will first consult with the fishing industry. A decision is expected late May.

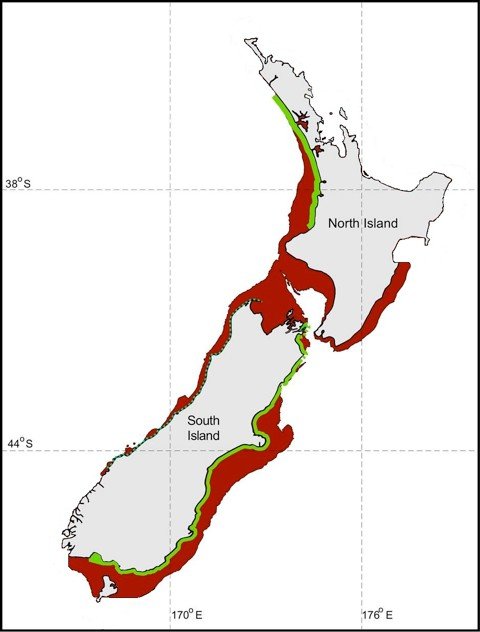

“I have no idea why a different offshore boundary was chosen off Taranaki (4 nautical miles vs 7 nautical miles further north). This certainly doesn’t make any biological sense. Basically, Hector’s and Maui’s dolphins are found in waters less than 100 metres deep – the red area in the map below. The green areas on this map are the existing protected areas.

“I have no idea why a different offshore boundary was chosen off Taranaki (4 nautical miles vs 7 nautical miles further north). This certainly doesn’t make any biological sense. Basically, Hector’s and Maui’s dolphins are found in waters less than 100 metres deep – the red area in the map below. The green areas on this map are the existing protected areas.

“As you can see on the map, one of the most important gaps in the protection measures is the area between North and South Island. Any dolphins that venture into this area have a very high probability of being caught in a gillnet or trawl net. This is a serious problem in terms of causing fragmentation of the population.

“The current government proposal also begs the question as to why they are not putting in place better protection in the harbours. A dead Maui’s dolphin was found in the Manukau Harbour late last year. And our research has also documented their use of the Kaipara Harbour, well beyond the current protected area.”

The report notes that there is a possibility that Hectors dolphins are interbreeding with the Maui populations. In your opinion is this likely? Is there a precedent for this in dolphins?

“Yes, this is certainly possible. Improved protection between North and South Island would facilitate better contact between populations and would provide a much more secure future for Maui’s dolphin.”

[1] Slooten, E., Dawson, S.M., Rayment, W.J. and Childerhouse, S.J. 2005. Distribution of Maui’s dolphin, Cephalorhynchus hectori maui. New Zealand Fisheries Assessment Report, Published by Ministry of Fisheries, Wellington. (Contact the SMC for a copy)

Dr Wayne Linklater, School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University commented in a press release:

“If we lose Maui dolphin it is likely that the effects will cascade through the food chain to radically change the community of plants and animals off our coasts. The loss of fish predators like dolphin can actually reduce ocean productivity for fisheries in the long-term.

“We need to understand that the loss of dolphin can be a bad thing for the economy as well as a bad thing for the quality of our environment and our enjoyment of it.

“The slowness with which the fishing industry and our political representatives act is a part of the problem. Calls for immediate action are warranted. We must act now not just because an early response has a better chance of rescuing a species, but because we can learn by acting. Even if measures prove ineffective we have learned what else might be tried.

“There is a solution out there somewhere. We are not going to find it by sitting on our hands. We can’t learn if we choose not to act.

“The genetic health of the population requires a larger number of breeding individuals. Every individual lost is a loss of the capacity of the species to recover and sustain itself. We have delayed long enough now to find ourselves in an untenable position. We act now or we lose a species. There is only one right choice. Act.”