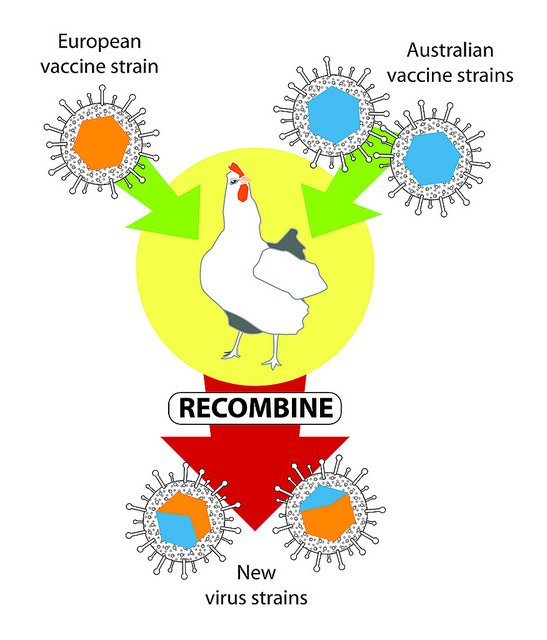

Researchers from the University of Melbourne have discovered that two different vaccines used to control an infectious disease in chickens have been able to recombine to generate new virus strains.

Their research was published today in the journal Science. The resulting new viruses have been responsible for significant outbreaks of disease and death in farmed chickens. The vaccines in question are known as live attenuated vaccines – and essentially contain weakened forms of the virus that causes the disease.

The findings of these studies have significance not only for vaccines in poultry, but also potentially for any live viral vaccine which might be capable of recombination, including those in use in humans.

More info can be found in this ScienceNOW news article.

The AusSMC held an online briefing with experts to explain this finding and discuss what the broader impact of this research is on both animal and human vaccine use.

The briefing can be viewed here.

SPEAKERS:

Dr Joanne Devlin is a Lecturer in Veterinary Public Health-Epidemiology at the Asia-Pacific Centre for Animal Health, University of Melbourne and an author of the research

Prof Glenn Browning is Director of the Asia-Pacific Centre for Animal Health, University of Melbourne and an author of the research

Dr John Owusu is from the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA)

Prof Ian Gust is Professorial Fellow Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Melbourne, also Chair of the Bio 21 Cluster and the Victorian Biotechnology Advisory Council

Our colleagues overseas also collected the following expert commentary. Feel free to use these quotes in your reporting. If you would like to contact a New Zealand expert, please contact the SMC (04 499 5476; smc@sciencemediacentre.co.nz).

From the Canadian SMC

Andrew A. Potter, Ph.D. FCAHS, Director and CEO, Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization (VIDO) and InterVac, and Professor, Veterinary Microbiology, University of Saskatchewan

“This is no big surprise, as most viruses are able, at least in theory, to recombine in the field. The classic example of course is influenza, but other viruses have also been show to do the same sort of thing. As far as risk goes, I guess it all depends on what is recombining, but if an attenuated vaccine strain (e.g. gene-deleted Herpesvirus such as those used in cattle) were to recombine with a more virulent isolate, all one would get back would be the more virulent strain which was there to start with. Ditto for two attenuated strains recombining. Thus, the risk is relatively small and must be looked at in the context of the reduction in pathogen load due to vaccination with these vaccines – there is no such thing as zero risk.”

From the UK SMC

Professor Paul Farrell, virologist, Imperial College London, said:

“The authors argue that new pathogenic strains have been created by recombination of the attenuated vaccine strains of this virus. Their conclusion is that recombination between the vaccine strains has occurred. This is quite possible but a bit surprising since it would imply that both vaccines have gone into the same animal, which would be required for recombination to occur.

“To my mind, the paper does not take into account sufficiently the possibility that recombination may have occurred between the vaccine strains and normal virus strains circulating in Australia at that time. It seems much more likely that the vaccine would encounter the normal circulating virus. The normal virus(es) present in Australia are not included in their Fig 1A.

“Having said that, it is obviously the case that live attenuated vaccines have the potential for recombination. The use of vaccines is always a risk-benefit calculation. There can be a variety of side effects from vaccines; many are well known. For example, we stopped immunising people against smallpox because the adverse reactions began to exceed the benefit as the disease was eradicated.

“Vaccines have been one of the great success stories of medicine and the type of important technicality raised in this article should not be allowed to detract from the enormous health benefit generally provided by vaccines.”

Dr Mike Skinner, virologist, Imperial College London, said:

“Evolution of novel variants of existing viruses is seen as a particular issue with poultry vaccination, where vaccines are routinely used as they are cheaper than antibiotics (and the latter are not permitted due to issues of residues in food and antibiotic resistance in humans). The vaccines are often used almost as a therapeutic to protect the particular flock from the ever present challenge of virus diseases (for the 6 week life of a broiler or the 2 years of a layer) rather than in a concerted way to try to eradicate the virus from the region. As a consequence, and just as with antibiotics, the global industry regularly sees variant viruses (sometimes

Prof Peter Openshaw, Director of the Centre for Respiratory Infection (CRI) at the National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, said:

“This is a highly plausible study, showing the importance of close monitoring and investigation of outbreaks of respiratory disease in livestock. Viruses are highly adaptable and will exploit every opportunity for self-improvement. We need to be constantly on the lookout for novel outbreaks and to intensify our study of the benefits and risks of well-intended vaccination programmes.”