You know that feeling – its gone 7pm in the newsroom and you’ve still to hear back from the two sources that are going to make your story worthy of page one or be spiked perhaps for ever. It’s that feeling of helplessness – no matter how fast you write, you’re at the mercy of other people to get your story finished.

The biggest single pressure on journalists has to be the time-constraints they are faced with in researching, writing and in the case of broadcast journalists shooting and editing, their stories.

Deadlines are great for producing results, there’s nothing like the feeling of nailing a story to deadline, then heading to the pub for a well deserved beer (mobile phone switched on in case the subs ring to fact check).

But the time frames in the world of new media are so truncated these days that turning around a well-researched, well-written story is often near-impossible.

Hence we get an increasing number of stories these days with quotes followed by “…she told the Associated Press”, or “according to the online encyclopedia Wikipedia”. Journalists just don’t have the time to do all the primary research themselves and the media tie-ups and content sharing deals going on encourage them to lift content from sister-publications.

The news embargo as it applies to journalism is designed to help out harried reporters by giving them a heads-up on a news story before the development is officially unveiled to the world at large. In the case of science news, one of the most embargoed areas of news globally, it also gives scientists time to read newly published papers before the news goes public and sparks a firestorm of interest.

Embargoes typically aren’t too common in New Zealand outside of the political sphere. The annual Government Budget announcements are the main source of embargoed information, as well as the traditional Budget lock-up, which allows press gallery reporters and increasingly, bloggers and columnists, to sit in on a briefing of the main budget items and read the reports, while promising not to rush out and report anything until the budget speeches are complete.

Companies generally select a few key reporters to give news to under embargo such is the extent to which embargoes are broken these days. In fact, in the world of technology news, such is the competition to get the latest gadget or Google development on the web, that reporters are immediately breaking embargoes. That has led influential tech commentator Michael Arrington of Techcrunch to “declare death to the embargo”.

It’s a bit more difficult for science reporters. The major scientific and health journals such as Science, Nature, The Lancet and the British Medical Journal enforce strict embargoes and journalists who break them are often banned from receiving further information under embargo.

Embargoes from these big journals are often timed to suit media in the Northern Hemisphere and therefore aren’t very convenient to New Zealand media (an embargo on New Zealand research in Science last week was set to be lifted at 8am effectively prohibiting newspapers from publishing it that day). But when embargoes work, they work very well. Often the UK embargoes will be set at midnight so that around lunchtime our time, the wires are flooded with news stories from the major papers and broadcasters in London. A big hit of news on a subject puts it on the agenda and lends importance to the story.

But with such a large flow of embargoed information coming through all the time, is the embargo system making journalists lazy? The World Federation of Science Journalists seems to think so.

“Embargoes encourage lazy journalism. Whereas embargoes can give journalists the time to really investigate a story, all too often they actually take away the stimulus and the need to do “good, old-fashioned, investigative journalism,” writes Frank Nuijens in a blog post on the WFSJ website.

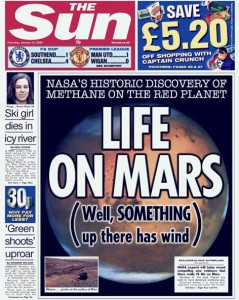

He points to the case of Paul Sutherland, a reporter writing for The Sun newspaper in Britain. Sutherland recently broke a major story about NASA on the front page of The Sun, the contents of which appeared to have come from an embargoed release issued to journalists by the science news aggregation service Eurekalert.

He points to the case of Paul Sutherland, a reporter writing for The Sun newspaper in Britain. Sutherland recently broke a major story about NASA on the front page of The Sun, the contents of which appeared to have come from an embargoed release issued to journalists by the science news aggregation service Eurekalert.

Suspecting Sutherland of breaking an embargo, the people at Eurekalert were understandably furious, ringing the paper to demand it be taken from the website and banning Sutherland from receiving future embargoed releases.

But it turns out that Sutherland’s story was down to his own research, not the information handed to other reporters on a plate by Eurekalert. He was able to prove such. Which makes you wonder about the majority of journalists who wait respectfully for embargo deadlines to pass – is this becoming such a way of life that the incentive to get out and dig up your own stories is receding?

I suspect there’s something to that. There’s another worrying trend towards scientific institutions packaging up content and handing it to media organisations to be reported largely verbatim. Granted, the scientific community deserves credit for learning how to develop content in a way that is going to see it getting a run in the media. But the long term potential impact for the state of science journalism is indeed worrying given the belt-tightening in the media in general.

So what’s to be done? Well, embargoes aren’t going away, everyone seems to agree on that. The alternative is chaos as journalists scramble to outdo each other when a story breaks or put pressure on contacts to leak information. That will do nothing for accuracy or balanced reporting.

A committee of journalists in Britain has been formed to look into the embargo issue in relation to science journalism and plans to have a draft report ready for the World Conference of Science Journalists in London in late June. The SMC will be at the conference and will report back on the findings of the committee.