Ten years after the devastating 2004 Boxing Day Tsunami, experts reflect on the event and how our understanding of these disasters has changed over the last decade.

At 2pm NZT on the 26th December 2004, a ~9.2 magnitude quake 160 km off the coast of northern Sumatra generated an immense tsunami, the likes of which the modern world had not seen.

At 2pm NZT on the 26th December 2004, a ~9.2 magnitude quake 160 km off the coast of northern Sumatra generated an immense tsunami, the likes of which the modern world had not seen.

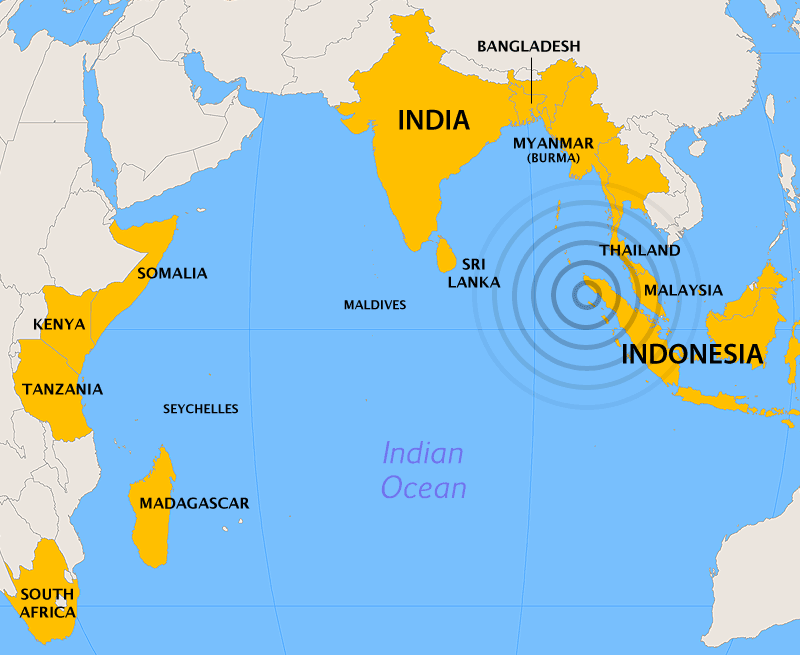

The tsunami killed over 230,000 people in fourteen countries and caused billions of dollars of damage.

Ahead of the ten-year anniversary, the Science Media Centre has contacted New Zealand experts for their views and thoughts on the event and the changes in knowledge over the last ten years.

Dr Rob Bell, Programme Leader: Hazards & Risk, NIWA, comments:

“The unfolding tsunami disaster was a shock globally, as it became the biggest tsunami event since the 1960 Chile event, four decades earlier. In my role as a tsunami advisor to the Ministry of Civil Defence & Emergency Management, working on Boxing Day at the office, it was hard to concentrate on the likely warning implications for New Zealand while the devastating news kept rolling across the TV and the internet. The first waves in New Zealand arrived around 6-7 am the next morning, but only reached a maximum wave height of 0.6 to 0.8 m – considerably smaller than the 30+ metre high waves that flowed overland in Banda Aceh.

“As the disaster response moved from the heavy rescue phase to relief and initial reconstruction, the NZ Society for Earthquake Engineering (NZSEE) assembled an inter-disciplinary team of six from NZ to survey the impacts and recovery operations in southern Thailand. I was part of that team in the capacity of a tsunami wave and coastal engineering expert. Reasons for going were the similarities to our infrastructure and topography and bringing home lessons applicable to New Zealand. Our reconnaissance team visited western Thailand from 24 January to 1 February, four weeks after the event, assisted by Thai government agencies. Already by then, some areas had been cleared of debris and work was underway rebuilding housing – but – the sheer scale of damage and destruction took days to sink in. Sobering to observe damaged three storey buildings, where the peak water level of 14 metres had reached the roof, and holes had been punched through the tiles in desperation to escape. Many tales of miraculous survival from those we interviewed – but also much sorrow and bewilderment of how this event had taken so many lives, many of them tourists from all around the world.

“The Boxing Day event paved the way for major advances in monitoring and associated warning systems, including in NZ through the GeoNet system. However, these warning systems are really only effective for tsunami sources more than 1-2 hours from the area of concern. New Zealand faces the potential for large magnitude earthquakes on our subduction margin, especially off the east coast of the North Island. With less than an hour travel time, residents will need to personally process and heed natural warnings such as “long or strong” ground motion to self-evacuate. However, the legacy of the Boxing Day tsunami has reinforced the need for us to be aware of those natural warnings including beach observations like receding or advancing tidal waters or a foaming wave front offshore.”

Dr Jose Borrero, Director of eCoast Ltd,comments:

“At the time of the 2004 tsunami I was 33 years old, a few years out of a Ph.D. and had nearly 10 years experience in post-tsunami data collection and damage assessment surveys, including work in Sissano and Aitape, Papua New Guinea in 1998 (~14 m tsunami, >2500 killed) and Camaná, Peru in 2001 (>10 m tsunami, ~400 killed), but nothing in my wildest dreams (or nightmares) prepared me for what I saw in Banda Aceh.

“I was working alone, trying to survey and document an incomprehensibly large disaster area. As I surveyed the area, I would regularly come across bodies in the piles of debris while at the same time, recovery teams were filling dump trucks with body bags. My reports from ‘ground zero’ were the first to bring the scale of the disaster out to the tsunami research and mainstream scientific community. As it turned out, surveys of the 2004 event continued across the Indian Ocean for the better part of 2005 with teams visiting and collecting data from every country on the shores of the Indian Ocean.

“Since then, what was a fringe discipline in earth science and engineering has gone totally mainstream and the global awareness of this phenomenon has increased significantly (which is a good thing!). In the intervening years we have had several significant tsunamis, including events in Java 2006, South Sumatra 2007, Samoa 2009, Chile 2010, Mentawai Islands 2010, Japan 2011, and most recently in El Salvador 2012 and northern Chile in 2014 (and yes it affected New Zealand, but not very much…).

“These days my work in tsunamis continues and I am presently completing a multi-year research project for the NZ Government looking at tsunami hazards in New Zealand ports and harbours. I hope to extend this work in coming years (if I get the funding) to fine tuning existing computer models to provide ‘faster than real time’ assessments of tsunami effects if/when another large trans-Pacific tsunami is making its way towards New Zealand. I am also working on tsunami hazard assessments for communities in New Zealand for the Waikato Regional Council.”

Dr Borrero has uploaded his entire collection of photos from Banda Aceh, taken less than 2 weeks after the Boxing Day Tsunami of 2004 (more here). At the time he was the first foreign scientist to reach the disaster area. Dr Borrero is travelling but can be contacted by email.

Dr William Power, Senior Geophysicist, GNS Science, comments:

“The Boxing Day tsunami started a process that lead to major changes in how we understand the threat of large earthquakes and tsunamis posed by ‘subduction zone plate boundaries’ i.e. where tectonic plates collide and one is pushed under another.

“The Boxing Day earthquake and the 2011 Tohoku (Japan) earthquake were both much larger than had been expected and planned for in those locations – with tragic consequences.

“To find a historical earthquake in Japan of similar size to the 2011 Tohoku earthquake we need to go back to AD 869. In Japan the tectonic plates are moving towards each other twice as fast as in New Zealand, so it is quite possible that the interval between the largest earthquakes here could be over 2000 years. Since the historical record in New Zealand only extends for about 200 years, we cannot rely on it to include the worst cases if these occur over intervals measured in thousands of years.

“Maori oral history includes descriptions of tsunami from before the arrival of Europeans, but it is difficult to interpret the specifics of where, when, and how large these events were.

“Many theories about which plate boundaries could experience the largest earthquakes have been contradicted, particularly by the tsunamis in Indonesia in 2004 and Samoa in 2009.

“Globally there has been a change in perspective, we now consider any subduction interface to be capable of large earthquakes and tsunamis until there is clear evidence otherwise. Since the written historical record of tsunamis in New Zealand is not adequate to tell us what can happen in future we must look instead to paleotsunami and paleoseismology to tell us what happened further in the past. And to geophysics to tell us more about what is happening on the plate boundary now.

“Paleotsunami evidence is steadily being uncovered suggesting that there have been large tsunamis on the east coast of the North Island (between Cook Strait and the East Cape) over the “past several thousand years. Paleotsunami evidence from Northland and the Coromandel area is consistent with there having been large tsunamis originating in the area between the East Cape and the Kemadec Islands over the past several thousand years.

“Geophysics now tells us much more about what is happening on the boundaries between tectonic plates – whether these are firmly stuck together, or are sticking and slipping at intervals, or are freely sliding past each other. But interpreting this information in order to better estimate the likelihood of future large earthquakes remains a major challenge.

Dr Ken Gledhill, Head of Department, GeoNet and Geohazards Monitoring, GNS Science, comments:

“The huge impact of the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami in the Indian Ocean changed our perception of tsunami forever. We all now understand the potential of these extreme natural events. Large tsunami had occurred previously in the Pacific Ocean, notably in the 1960s leading to the establishment of the Pacific Tsunami Warning System in 1965 (next year marks the 50th anniversary). None had caused the huge loss of life and been such profound media events (until the Japan tsunami of 2011).

“The Boxing Day tsunami was the start of a decade of destructive tsunami. These include the 2007 Solomon Islands, 2009 Samoan Islands, 2010 Chilean and 2011 Japan tsunami in the Pacific. All caused significant loss of life and damage near-source, and tsunami warnings in New Zealand, with tsunami surges on our coasts of more than a metre recorded, including minor inundation.

“The Pacific Tsunami Warning and Mitigation System (PTWS) was the only tsunami warning system before the Boxing Day tsunami, but is now one of four globally covering the world’s oceans.

“Tsunami warning in New Zealand has changed considerably and now uses tsunami forecast models to establish the potential threat in pre-defined coastal zones. The threat levels can be used to inform evacuation decisions based on already-planned evacuation zones and routes. The whole warning system is now much more end-to-end. GNS Science act as the science advisors to Ministry of Civil Defence and Emergency Management, employing forecast models and the expert knowledge of the “Tsunami Experts Panel”, a group of New Zealand based tsunami scientists.

“On 1 October this year PTWS updated its tsunami warning capability using similar techniques to those we currently employ in New Zealand. Now the Pacific Tsunami Warning Centre in Hawaii (the operational centre of PTWS) sends pictorial and text messages to member countries based on tsunami forecast models and the expected impacts on coastlines. This replaces the messaging based solely on the size and location of possible tsunami generating earthquakes.

“New Zealand is now well served by PTWC and the advice provided by GNS Science (via GeoNet and the Tsunami Experts Panel) for distant and regional tsunami. But we still rely totally on natural warnings (feeling high levels of, or long lasting shaking , and unusual sea behaviour)for local-source tsunami (earthquakes or triggered undersea landslides near our coast) warning.

“Very few countries attempt local tsunami warning, but there are some situations in New Zealand where a tsunami-causing earthquake may not be felt strongly, leaving a potential gap in our tsunami warning strategy. On the east coast of the North Island we like above a huge fault (the subduction zone) where the Pacific tectonic plate meets and is pushed down below the Australian plate. Many earthquake types can happen in this process, including “slow” earthquake which will not be strongly felt. And further north of New Zealand, a very large earthquake could send a tsunami towards populated parts of the upper North Island without high levels of shaking being felt on-land. Work continues on the science and technology necessary to provide official warnings for these local events which may provide only minutes to 10s of minutes of warning time.

“There is no substitute for education and the heeding of natural warnings, but if resources were no object New Zealand should consider the establishment of a local-source tsunami warning capability.”

Dr Gledhill has also written about the Anniversary on the GeoNet – Science in Action blog.

Dr Emily Lane, Hydrodynamics Scientist, NIWA, comments:

“The 2004 Boxing Day tsunami was a wake-up call. Prior to it, the India Ocean was not seen as a place with a significant tsunami hazard – large tsunamis happened in the Pacific Ocean, usually generated by earthquakes off the coasts of Japan, Alaska or South America. I have just come back from a conference in India on the Boxing Day tsunami and many of the Indian scientists, who experienced it first-hand, freely admitted that they had never even heard the word before – let alone knew how to pronounce it. Happily, India now has a strong core of tsunami researchers working hard to understand their risk.

“By contrast, New Zealand knew it had a tsunami hazard (I remember learning about ‘tidal waves’ – as they were then known – back in primary school) but many didn’t really know what that meant. The Boxing Day event showed the power of tsunamis, bringing them into the spotlight. The more people are aware of tsunamis and know what to do when one occurs, the safer they are. When people forget or become complacent, the risk increases. More recent tsunamis in the South Pacific, Chile and Japan have kept this memory fresh and have given civil defence a chance to practice and refine their response, identifying and correcting problems. Initiatives like the blue line in Wellington also maintain awareness.

“One of the main lessons to come out of the Boxing Day tsunami was ‘Watch out for unknown unknowns.’ Tsunamis aren’t common, so common sense – ‘There’s never been a tsunami here before in my lifetime’ – doesn’t apply. This is where science is important. Science can help us both look back into the past and try to predict the future to understand our tsunami risk.

Archaeological and palaeo-tsunami research (identifying past tsunamis from layers of sediment they deposit) have identified that tsunamis around the fourteenth century destroyed Maori villages around New Zealand and caused some tribes to move inland. This work is vital in understanding how often large tsunamis hit New Zealand but it is difficult and painstaking work and more needs to be done.

“Geophysical understanding of what causes tsunamis together with computer modelling shows how big the hazard could be, so that we can plan for it. A collaboration between NIWA and GNS is assessing the hazard to Wellington from tsunamis generated by submarine landslides in Cook Strait Canyon. We know that landslides occur – we can see the tell-tale scars on the sides of the canyon – and we know that submarine landslides cause tsunamis. We want to know how bad it could be before one happens – not after.

“Tsunami science has come a long way in the last ten years. We can assess the risks more accurately and that means our emergency response plans are better. But there is always more we can learn, especially from disasters like the Boxing Day tsunami, to keep the world safer in the future.”

David Coetzee, Manager, Capability & Operations, Ministry of Civil Defence & Emergency Management, comments:

“As a result of the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami the Ministry of Civil Defence & Emergency Management (MCDEM) commissioned GNS Science to deliver a report on the tsunami hazard and its risk in New Zealand to establish an “official” understanding in this regard. The Review of Tsunami Hazard and Risk in New Zealand was published in 2005.

“The report was the stimulus for the establishment of a Tsunami Risk Management Programme led by MCDEM. The Programme involved further investment in the development of tsunami modelling to support threat forecasts and warnings, the establishment of a National Tsunami Advisory and Warning Plan as well as consistent standards for tsunami signage, sirens and public messaging, and the issue of national guidelines on tsunami evacuation zones as well as public alerting options. These documents are all available on the MCDEM website.

“As part of the on-going Tsunami Risk Management Programme, MCDEM recently commissioned GNS Science to update the 2005 Review of Tsunami Hazard and Risk in New Zealand to take account of research and changes in scientific understanding of tsunami since 2005. The update was published in August 2013 and can also be found on the MCDEM website. A substantially revised probabilistic model was constructed for the updated report, which for the first time estimates the tsunami hazard for all parts of the New Zealand coastline, and takes into account all sources of earthquake-generated tsunami (local, regional and distant) – where-as the 2005 report focused only on the main urban centres and did not account for local source tsunami.

“The Programme is still on-going and besides continuous review and updating of the guidelines, it now also starts to direct its focus towards further subjects such as land use planning from a tsunami hazard perspective and vertical evacuation design specifications. A seminar was held in Gisborne in October 2014 to start discussion on these subjects.

“Several countries have upgraded their public alerting a capability since the Boxing Day tsunami. MCDEM is currently leading a project aiming at the establishment of a national public alerting system for New Zealand. Currently the warning systems used by agencies vary and have mixed capabilities, resulting in a fragmented and inconsistent approach. There is also no capability to target warnings directly to only those communities that are at risk in a given geographical area. The project aims to address these weaknesses and a business case is currently being prepared. While the focus is on any serious, immediate threats (the project includes the emergency services and other agencies) successful implementation will significantly enhance our ability to communicate with targeted communities during a tsunami warning.”