2015 has got off to a very dry start and increasingly drought-like conditions could have a substantial impact on farmers in the coming weeks.

Soil moisture measurements in both the North and South Islands are lower than average for this time of year, with irrigation restrictions already in place in parts of Canterbury and North Otago.

While DairyNZ reports that levels of grass cover and supplementary feed supplies are currently good, scientists suggest continuing dry conditions through January and early February could see parts of the country hit by drought.

Regional data on soil moisture can be found in NIWA’s latest Hotspot Watch Alert.

The Science Media Centre contacted New Zealand climate and agribusiness experts for comment on the current dry conditions and how farmers will cope with increasingly dry conditions in future.

Dr Andrew Tait, Principal Scientist – Climate, NIWA, comments on the current outlook:

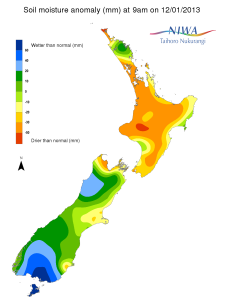

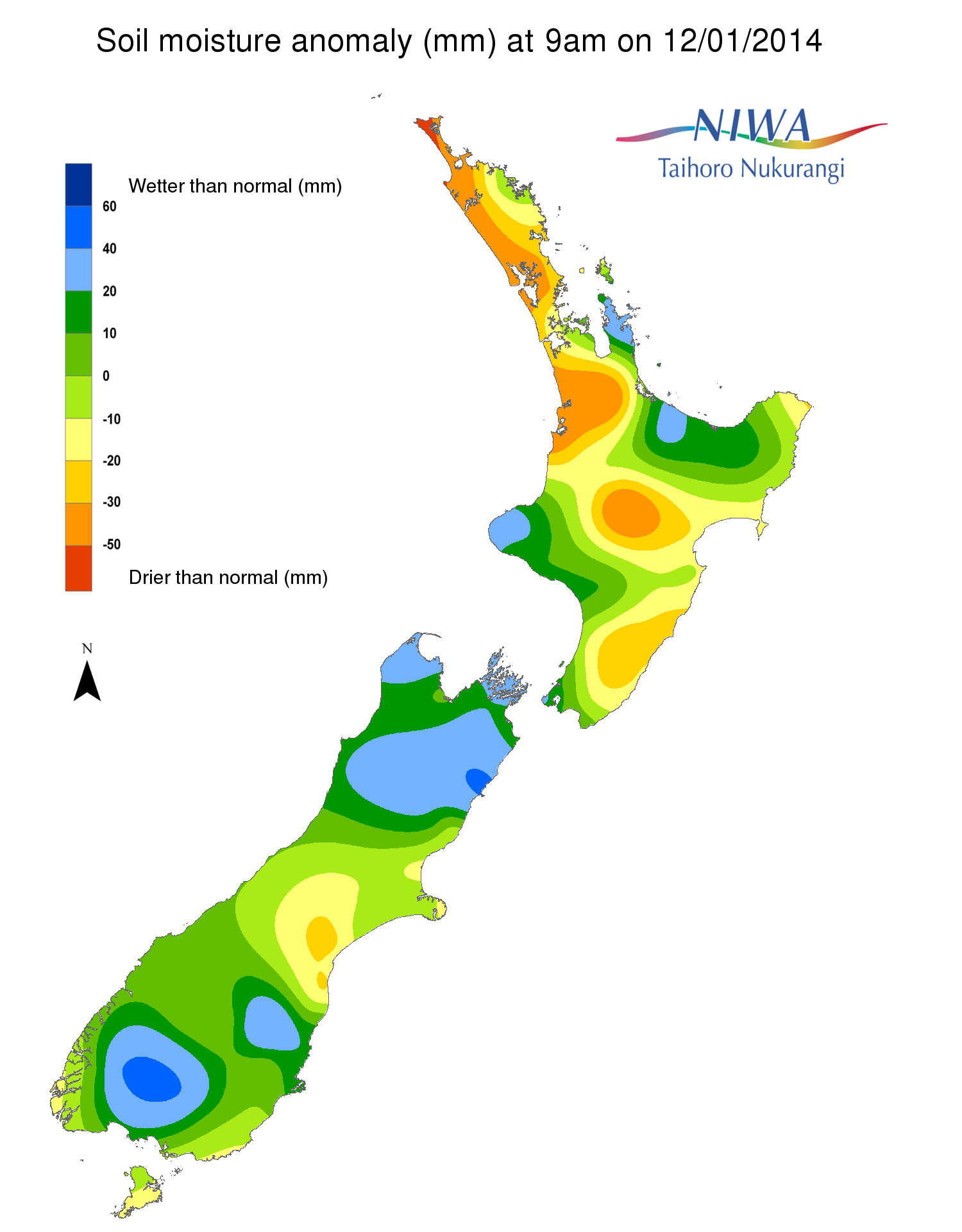

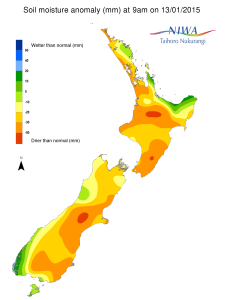

“The best source of information I can provide is the soil moisture maps that are updated daily on NIWA website. In particular, the soil moisture anomaly map compares the current conditions to the historical average for this time of the year. It can be seen from the latest anomaly map that soil moisture is well below normal for much of the country, which is indeed a cause for concern.

“Looking back over the last couple of years, I’ve included the same anomaly plots for 12 January 2014 and 12 January 2013 [below]. This makes for an interesting comparison. In January 2014 there was only really pockets of drier-than-normal soils (most notably the north of the North Island), and in January 2013 it was the whole North Island that was affected (but not bad at all for most of the South Island).

“So, potentially, if there is no significant rainfall for the next month or so, we could be heading into one of the worst nation-wide droughts we’ve seen for some time.”

Professor James Renwick, School of Geography, Environment and Earth Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington, comments on the wider climate trends:

“Based on the latest projections, New Zealand is still on track to see increased drought occurrence in eastern regions and over the northern part of the North Island, as a result of human-induced climate change. This is a result of two things, the gradual southward expansion of the subtropical high pressure belt and gradually rising westerly winds over the South Island, especially in winter and spring.

“How much the drought frequency increases depends on how much more CO2 and other greenhouse gases we put into the atmosphere. Compared to the late 20th century, there is likely to be at least a doubling of the occurrence of agriculturally-significant droughts in the regions that are currently very dry.

How can the agricultural sector become more drought resilient?

“A drier regional climate can be handled in two ways. First, if rivers and other water bodies provide sufficient water for irrigation, it may be possible to continue with present-day farming practices. Increased water storage would be one approach along these lines. Second, more dryland-style farming practices could be adopted, using more drought-resistant crops and species, and reducing farming intensity and so on.“

Jacqueline Rowarth, Professor of Agribusiness, University of Waikato, comments:

We have seen warnings about increased drought risk over the last few years, has there been a shift towards making farms more drought resistant?

“On cropping farms and horticultural enterprises, irrigation is an increasingly common method to increase resilience as it enables consistency of yields. Irrigation is also a boon on farms with animals to ensure that pasture and fodder crops still grow. An added benefit of the growth is that soil carbon is maintained. When soils are hot and dry, soil micro-organisms have a greater capacity to keep active than do plants and as a consequence the soil organic matter which they use as an energy source decreases.

“What we are seeing at the moment, however, is that irrigation is not 100% reliable – water restrictions mean rationing and as a consequence plant yields are affected. This puts immense pressure on farmers and growers and is part of the reason that water storage is required. At present over 98% of water (not including that used for hydro-electricity) runs out to sea. The government’s overview of freshwater reform states that New Zealand receives 608 billion cubic metres of water annually, but uses only 1.8% (excluding hydro-generation). Just over half of that 1.8% is used in irrigation, 23% by industry, 17% in drinking water and 7% is used by stock.

“On farms where animals are involved, when pasture and crops don’t grow, animals have to be sent to somewhere else where there is food, fed with food from somewhere else, or sent to the works so that they don’t need food any more. Widespread drought means that the option to move animals is reduced. Using food grown somewhere else has been increasing this century – maize grown on farm (replacing pasture – remembering that maize yields can be 25 tonnes plus 5 tonnes annual ryegrass during the winter, whereas pasture under non-drought is maybe 15 Tonnes per hectare for the year) or on a specialist block and ensiled, for instance, or Palm Kernel Expeller brought in from overseas. Tapioca, kiwifruit, brewer’s grains… many different energy sources are used as supplements and the determinant is availability and price per unit of energy.

“The important factor in efficiency is being able to convert the purchased (or on-farm grown silage) feed into production – and that is why the number of feed pads and shelters (generally with covered feed troughs) have increased significantly. Of note is that in some areas of the Waikato, stocking rate has decreased but production increased because of more efficient feeding enabled through feed pads/shelters.”

The drought, coupled with low milk payouts, could have a substantial financial impact on dairy farms. Is it possible we may see some farms move away from dairying?

“A move away from dairying isn’t likely at the moment because beef, sheep and venison (termed drystock) isn’t providing sufficient returns. What might happen is that the drystock farms currently providing dairy support (heifers, dry cows and winter grazing – which have been providing higher returns than drystock) aren’t affordable by the dairy farmers – so they will keep the animals on the home farm and reduce numbers and the drystock farmers will lose more money and so be less resilient.

“The low payout will, however, be a factor in deciding on future conversions.

“The fundamental problem in all of this is that the price farmers receive for their product has not kept up with the costs of production – and consumers are benefiting from the fact that food as a proportion of income is smaller than ever (incomes rise faster than food prices). Farmers are employing modern technologies to improve resilience (and reduce environmental impacts), but they require capital investment which is difficult to accumulate when prices for product are low.”