Is GM food safe to eat? Are humans responsible for climate change? Should we use animals in research? The views of scientists on these contentious questions are often very different from the public’s, according to a wide-ranging US survey, and highlight need for better dialogue.

The Pew Research Center, in collaboration with the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), conducted a survey of 2,000 members of the general public and over 3,700 AAAS scientists, gauging attitudes on a number of issues related to science and society. The findings will be highlighted in the journal Science.

The report found significant differences in views on science-related issues.

For example:

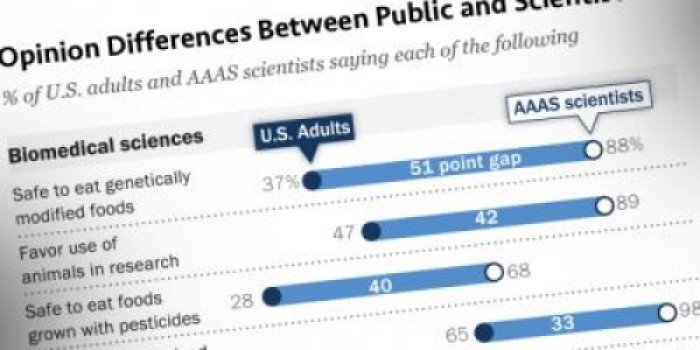

- 88% of scientists think eating genetically modified food is safe, while only 37% of the public agree.

- 89% of scientists support the use of animals in research, compared to 47% of the public.

- 87% of scientists polled agreed that climate change is mostly caused by human activity, compared to 50% of the public.

- 52% of the US public favour increased offshore oil drilling, while only 32% of scientists do.

“Such disparity is alarming because it ultimately affects both science policy and scientific progress,” writes Alan Leshner, Chief Executive Officer of AAAS, in a related editorial published in Science. “Speaking up for the importance of science to society is our only hope, and scientists must not shy away from engaging with the public, even on the most polarising science-based topics.”

The full report and press material are available on the the Pew Research Centre website.

Here in New Zealand a similar recent survey from the Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment found that Kiwis consider science important for New Zealand’s international competitiveness, improving health and preserving the environment. However, half of New Zealanders report that there is too much conflicting information about science and technology “making it hard to know what to believe”.

Dr Nicola Gaston, Principal Investigator, The MacDiarmid Institute for Advanced Materials and Nanotechnology, Victoria University of Wellington and President of the New Zealand Association of Scientists, comments:

“Despite positive attitudes to science as a whole, there are some issues of concern in this survey, which we would do well to consider in the New Zealand context. In general, the disagreement between scientists and the public on the risks of issues such as GM, climate change, and the use of animals in research is not so surprising. While it is tempting to see these disagreements in terms of a simple ‘information deficit’ model, in which the public are simply uninformed and therefore resistant to change, it is actually quite understandable that individual values and experience will win out when weighed against scientific knowledge with which you have little or no direct involvement. However, the agreement between scientists and the public about the relatively poor quality of STEM education does suggest that there is a broad recognition of the need for knowledge to be kept up to date.

“Of particular resonance is the fact that only 15% of scientists believe that policy choices about land use are guided by the best science: and only 27% believe the same for air and water quality. This is a concern: policy need not be dictated by science, but the best scientific advice should be accessible and part of public conversation on these issues. A reason that it is not, is perhaps most clearly suggested by the perception of the degree of scientific consensus – on evolution, climate change, and the big bang – on which the public are strongly split. Trust in scientific opinion goes hand in hand with an understanding of the nature of science, and the degree to which scientific knowledge is built upon replication and rebuttal. This includes an acceptance that disagreement, and the open acknowledgement of uncertainty are part of the process. It appears that this understanding remains one of the most important challenges for effective science communication, and for the effective use of scientific knowledge in policy.”

Dr Fabien Medvecky, Lecturer, Centre for Science Communication, University of Otago, comments:

“The new Pew Research Centre survey of views on science and society in US, (commissioned by American Association for the Advancement of Science) was much like its previous iteration of 2009, except for two very surprising and quite alarming findings. Firstly, the public’s view of U.S. scientific achievements is substantially lower than working scientist’s view of the same. Only 54% of the general public thought American scientific achievements were either the best or among the world’s best compared to 92% of scientists. Indeed, other findings from the survey show an overall decrease in the level of admiration for science in the American public. While most Americans think science has, overall, made life easier rather than more difficult (79% easier to 15% more difficult), this is a decrease from 5 years ago (83% easier to 10% more difficult). Secondly, there is a new pessimism amongst scientists in America, with nearly half (48%) stating this is a bad time for science in America, compared to 23% in 2009. Comparatively, New Zealanders are quite positive about science. Despite a large proportion of Kiwis feeling that science is too specialised for them to understand (35%), New Zealanders are much more positive about science than Americans, and more supportive of government funding for science (NZ-69% compared to US-61%).

“While there are innumerable difference between our country and the US (so points of comparisons are limited), there are a couple of key differences, and they have nothing to do with science as such. The first is the overall mood in each country; NZ is going through a prosperous period and we are currently one of the best performing countries in the world. The US, on the other hand has seen an increased pessimism about its capacity, not just in relations to science, but with regard to almost all aspects. Indeed, in the 2009 Pew survey, 50% of Americans thought the US political system better than average compared to only 34% in 2014. The same decrease can be found with regard to military might (79%, down from 82%) or the health care system (26%, down from 39%). With such wide ranging pessimism, it seems no only reasonable that science follow along.

“The second, and more important difference is that science in NZ is largely regarded as non-political, and is treated as such in the media. In the US, on the other hand, science and scientific findings are made political. Just recently, congress agreed that climate change is real. Now think about that for a minute; policy makers given the right to decide which facts about the world are real and which are not. What matters here is not about which party supports what; the point is that all parties are using science as a political pawn, and by making science part of politics, they make its findings “up for grabs”. This politicisation of science, both in the media and by the political parties undermines the seeming validity of scientific research, and if science is less valid, then it’s probably not as good as it used to be, and it’s probably doing less to make our lives useful.

“Here we are fortunate that the New Zealand media and our political parties treat science and scientific findings with respect (even if some of us would like to see more funding for science and more science in the media).”

Dr Alison Campbell, Associate Dean, Teaching and Learning, University of Waikato, comments:

“From an education perspective it’s clear that in the US, as in NZ, both scientists and the wider community value the STEM subjects and what they offer to society.

“I was a little concerned to see the summary document skirting around the ‘information deficit’ model (if people only knew more they’d recognise why this is important), when in fact people’s reasons for opposing a given aspect of science or technology are considerably more complex than that. Happily the AAAS editorial makes this clear, but it’s something I’ll touch on later.

“While nearly 80% say “science has been a positive force in the quality of U.S. health care”, that still means that 1 in 5 held the contrary view. Furthermore, “only 26% said U.S. “health care” was the best or above average.” While I recognise the impact of partisan politics in this, I’m moved to wonder what part the rise of ‘alternative medicine’ plays, given the widespread prominence of alt.med. advocates in US mainstream-media & on-line. (In fact, it’s ironic that the AAAS & Science magazine have chosen to run a series of guest editorials on alt.med – this can only muddy the waters around perceptions of healthcare.) In NZ, the ‘natural health’ lobby is quite active and may well colour local opinion in a similar way.

“US scientists are far more critical than the public of the standard of STEM education in the compulsory sector, and I suspect we would see a similar disparity in NZ. This is understandable in the sense that scientists may feel that science education doesn’t adequately prepare students for a future world in which science & technology will play a major role. But it may also reflect a fairly widespread belief that if students (& ‘the public’) are simply given more facts, their understanding of & attitudes to science will improve . If so, this fails to recognise the impact of other factors, such as religious beliefs and personal morality, that can also have an impact, and highlights an area where scientists and science communication still Must Do Better in terms of actual engagement with the public.

“Some interesting minority views: “62% say science’s impact on food is positive; and 62% say the same thing about the impact of science on the environment.” That is, a sizeable minority (nearly 40% answered in the negative on these questions. The ‘food’ answers could in part reflect the current prominence of anti-GMO lobby groups, & it’s quite possible that New Zealanders might answer in a similar vein (I see there’s a ‘March against Monsanto’ scheduled in Auckland, for example). “This is examined further in chapter 3 of the report, which notes that “88% of AAAS scientists say it is generally safe to eat genetically modified (GM) foods”, but only 37% of the public agreed with them. This is definitely an area where personal beliefs and ethics come into play, and it’s not a gap that’s going to be closed by simply throwing more facts at it – a conclusion was reached by our own Royal Commission into genetic modification. The survey found similar differences in opinion regarding other contentious issues, such as climate change, pesticide use, evolution, & vaccination, which would probably also be mirrored in NZ. (It was both surprising and alarming to see that 14% of AAAS scientists did not support the statement than childhood vaccinations should be required.)

“From a science communication perspective, and from the point of view of an educator, I think these findings highlight a need for us to look very carefully at how we communicate around issues of high public interest and significant scientific and societal and cultural