A court case is currently underway in which a District Health Board is seeking guardianship of an HIV-positive boy being refused treatment by his father, as reported in the New Zealand Herald over the weekend.

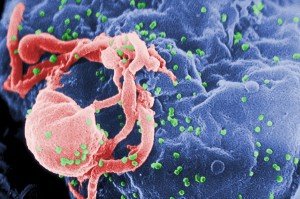

Credit: C. Goldsmith/CDC

The case has opened discussions about the rights of parents whose children are HIV-positive, the rights of children to know their health status, and whether parents should be obliged to inform schools of children that are HIV-positive.

Final submissions on the case will be held on 17 February.

The SMC collected the following expert commentary. Feel free to use these quotes in your reporting. If you would like to contact a New Zealand expert, please contact the SMC (04 499 5476; smc@sciencemediacentre.co.nz).

Associate Professor Christa Fouché, Head of School in Counselling, Human Services and Social Work, University of Auckland, comments:

“I find the recent development about the court case to ensure a HIV positive child receives treatment for his condition both sad and disturbing. It is very sad for the family concerned, but most disturbing as this reflects the lack of understanding about HIV and antiretroviral treatments. That HIV is a ‘death sentence’ and that there is no link between HIV and AIDS is no longer true. There is lots of evidence for that.

“What I found most upsetting, was that this 9-year old is allegedly unaware of his HIV status – which is highly unlikely if he has been subjected to debates about his condition for many years. However, it does raise an issue for many parents who have to deal with the tension of breaking news about HIV to their children. They need health professionals to assist them with breaking the news, managing the implications thereof and ensuring that the child can take responsibility for his health now and in the future.

“To me, the father’s comments are indicative of larger concerns related to how the boy potentially contracted the disease, about his relationship with his child and with the health professionals working alongside his family.

“A better understanding is needed among New Zealand’s wider health and social services about HIV and how to support families living with the consequences of this condition. Other families have found support groups such as Positive Women, Body Positive and the New Zealand AIDS Foundation helpful to connect with others in similar situations. I am hoping this will be true for this child and his father as well.”

Dr Peter Saxton, HIV prevention researcher at the Department of Social and Community Health, University of Auckland, comments:

“The recent case of an HIV positive child raises broader questions about schools’ duty of care. Some schools for example are arguing they need to be informed about a child’s HIV status in order to protect other students.

“There isn’t a legal duty for parents to disclose their child’s HIV status, because HIV isn’t casually transmitted in school settings. HIV is only transmitted under specific circumstances; HIV positive children at school don’t give other kids HIV. In the event of a blood spill, all schools should treat the blood as potentially harbouring an undiagnosed blood borne infection, such as hepatitis, and respond with appropriate caution.

“Unfortunately a minority of people do expect to be told about a person’s HIV status, only to respond irrationally. In fact, they’re often the same people who want to avoid taking personal or organisational responsibility for preventing infection, who don’t know the facts about the virus, or who want to stigmatise people with HIV.”

Dr Saxton recently commented on an exhibition about HIV at Michael Lett Gallery.

Dr Mark Thomas, Associate Professor in Infectious Diseases, University of Auckland, comments:

“Without effective treatment HIV infection inevitably eventually results in gradual progressive damage of the immune system and the subsequent development of severe unusual infections and cancers (AIDS illnesses). In some HIV infected people the rate of destruction of the immune system is relatively fast, while in others it may be much slower.

“The degree of damage to the immune system can be monitored by measuring the number of helper lymphocytes (CD4 cells) that are present in an HIV infected person’s blood. The lower the level of CD4 cells the greater the risk of the person developing an AIDS illness. Without any treatment of their HIV infection by the age of 5 years, approximately 25% of children will have died from an AIDS illness, and another approximately 25% will have developed one or more AIDS illnesses but still be alive. A small minority of HIV infected children will survive into adulthood before their immune system becomes severely damaged and they will not be at risk of developing an AIDS illness until then.

“Treatment of HIV infection, with medicines taken once or twice a day, can stop the replication of HIV, halt the destruction of the immune system, and allow recovery of the immune system, if damage has already occurred. While adverse effects from many HIV treatments were relatively common in the past, these complications are less common and less severe with many of the newer drug treatments. However, intermittent drug treatment (when a patient does not consistently take their medicines every day) can result in emergence of mutant viruses, that are resistant to one or more of the medicines the patient is (intermittently) taking. If this happens the utility of these drugs may be lost forever, for that person.

“Doctors commonly recommend that treatment of HIV infection be started if the blood tests show that the number of CD4 cells in the blood is so low that there is a significant risk of the person developing an AIDS illness. Because untreated HIV infection can also commonly damage the brain, concerns about HIV infection causing intellectual retardation may also be considered. A further consideration is that treatment reduces the level of HIV in the blood and genital secretions and dramatically reduces the possibility that HIV is transmitted to another person.”