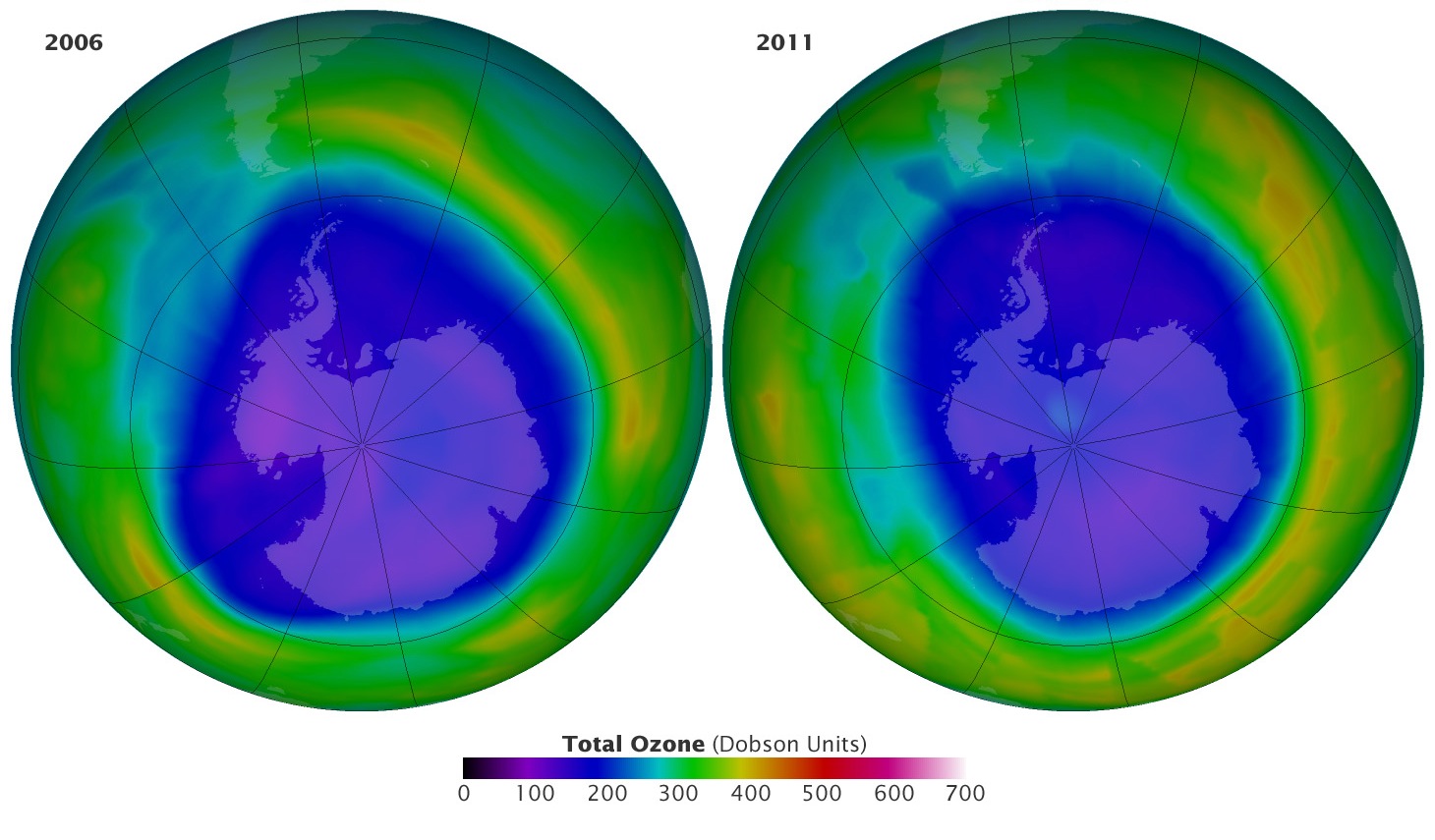

While the ozone holes in the poles are recovering, ozone levels are still dropping everywhere else between Russia to the Southern Ocean (between 60⁰N and 60⁰S), according to international research published in the journal Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics.

While the ozone holes in the poles are recovering, ozone levels are still dropping everywhere else between Russia to the Southern Ocean (between 60⁰N and 60⁰S), according to international research published in the journal Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics.

While ozone levels in the upper atmosphere have been recovering near the poles in recent years, this new research has found that the bottom part of the ozone layer at more populated latitudes is not recovering. They don’t know exactly why this is happening, but the researchers suggest it might be a product of climate change or caused by other shorter-lived ozone-destroying chemicals found in solvents and paint strippers that weren’t included in the Montreal Protocol.

The Australian Science Media Centre gathered expert commentary on the research. Please feel free to use these comments in your reporting.

Professor Steven Sherwood, UNSW Climate Change Research Centre, said:

“This finding is very interesting for scientists but I don’t think it has any broader significance yet.

“The authors do not call into question the prevailing view that the ozone layer is entering a recovery phase after the damage caused in the 1980’s and 90’s by refrigerant gases, which were phased out by the Montreal Protocol.

“They do find a curious ozone decrease in a particular altitude range below the main ozone layer, which suggests that changes to the atmospheric circulation may have happened up there. The community will have to look at this more carefully before we know what it means.”

Emeritus Professor Ian Lowe, Griffith University, said:

“The amount of ozone-depleting substances has been reduced dramatically, from about 1.5 million tonnes of chlorofluorocarbon (CFC)-equivalent to 0.3 million. It has not been reduced to zero.

“The reduction in the rate of release of these chemicals has halted the worsening of ozone depletion, but we are not yet seeing significant repair.

“This paper also shows that the system is complicated and there are still aspects we do not understand well enough to model the observed data. It should be another urgent reminder that we must scale back our assault on natural systems if we are to achieve our stated goal of living sustainably.

“Since we have known for more than forty years that a group of chemicals weakens the ozone layer, which protects all life from damaging ultra-violet radiation, phasing these chemicals out completely should be a high priority.”

Dr Paul Read, Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute, said:

“Although the authors suggest otherwise, this paper could be a challenge to the effectiveness of the Montreal Protocol.

“Ozone, like atmospheric carbon, is critical to maintaining the survivability of Earth’s solar budget – all of life depends on them being maintained in a tight range. Ozone we need; too much atmospheric carbon we don’t.

“This is because energy from the Sun comes in three types – per kilowatt, 32 watts is ultraviolet (UV), which destroys DNA, 445 watts is visible light, and 526 is infrared, the stuff you feel as heat.

“Whereas a thin film of ozone protects us from the DNA scrambling effects of UV, a growing film of carbon emissions lets infrared waves in but then traps them, causing the Greenhouse effect. As for ozone, most people know that our wholesale use of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) amassed in the atmosphere and created a hole in the ozone layer that was then exposing us to cancer-causing UV light.

“For fear of skin cancer, Australian beach culture changed overnight – the ‘slip slop slap’ campaign, the invention of rashies, etc. It took a whole world effort to ban CFCs – every country and every industry – and we went, for example, from spray cans to roll-on deodorant pretty quick smart.

“The Montreal Protocol banned CFCs and was the world’s first universal agreement to cooperate on behalf of global human health. Kofi Annan said it was a great sign of hope that the world could be civilised enough to do the same for climate change; estimates say it’s already saved many more than 280 million lives.

“What this new paper is saying is that the hole in the ozone layer, predicted to be completely repaired by around 2060, has a whole section that’s not repairing itself. And they want to know why!

“The section in question is about 20 kms above Earth, between the tops of clouds and the height where aeroplanes cruise, and extends from just outside the Arctic circle to the start of Antarctica.

“Even though the polar regions and the higher stratospheric levels of ozone are repairing themselves, this lower, middle section is going in the opposite direction – the amount of ozone is still falling just like it was before the Montreal Protocol.

“A million things could be causing this, some natural, some not. But this paper tries with all its might to get around a host of past problems to see the real trend – and the ozone is definitely falling in that region, even after seasonal, time series and measurement adjustments.

“After eliminating the obvious, they’re still left with some disturbing possibilities: did we underestimate the anthropogenic effect, the volcanic effect, or is there some missing chemistry?

“What they propose are three explanations related to climate change: firstly, an expanded troposphere; secondly, an accelerating Brewer-Dobson circulation; or thirdly, a disproportionate acceleration of it closer to the tropopause. In other words, the ozone is being transported out of this section faster.

“If so, it’s a worry because it means the actual repair might be due to more rapid accumulation in the higher stratosphere, rendering the Montreal Protocol targets perhaps too lax from the beginning, that is, unless the higher stratosphere is actually doing the lion’s share of protecting us from UV radiation.

“This paper suggests climate change is interfering with the ozone system as well, creating a scenario where the Montreal Protocol, although still necessary, might not yet be sufficient, for repair by 2060.”

Ian Rae, honorary Professor at the Univesity of Melbourne, said:

“We know that the worst ozone-depleting substances are chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and other volatile chemicals containing chlorine or bromine. Emissions of these substances have been drastically reduced by international agreement, under the Montreal Protocol, to ban or restrict their production and consumption. As a result (we’d like to believe), the decline in the stratospheric ozone concentration has been arrested and there are some signs of recovery.

“However, given the steep decline in emissions, we might have expected a better result for the ozone layer. This analysis of research results, published by an international group of scientists, help us to understand why we haven’t. In short, the outcome is a curate’s egg: good in parts.

“Measurements of ozone concentration are made for a notional column of air stretching up from about 10 km above earth’s surface to about 50 km. As an aside, it helps to use round numbers to convey the message because there are variations with seasons and with latitude – position on the earth.

“For the column as a whole, there has not been much change in ozone concentration during the period 1998-2016. When results for ‘slices’ of the air in that column were examined, a more complex picture emerged. In the upper stratosphere (32-48 km), there has been a steady increase in ozone concentration, which is what was expected from the actions taken under the Montreal Protocol.

“However, in a lower slice of the air column(13-24 km), there has been a continuous decline. The reasons for this decline remain unknown. Unlike the positive change at higher levels, this negative is not predicted by models of atmospheric chemistry.

“The result of their analysis is nicely summed up by the authors: “We find that the negative ozone trend within the lower stratosphere between 1998 and 2016 is the main reason why a statistically significant recovery in total column ozone has remained elusive.

“In colloquial language: if you add a positive change and a negative change, you get zero change.”