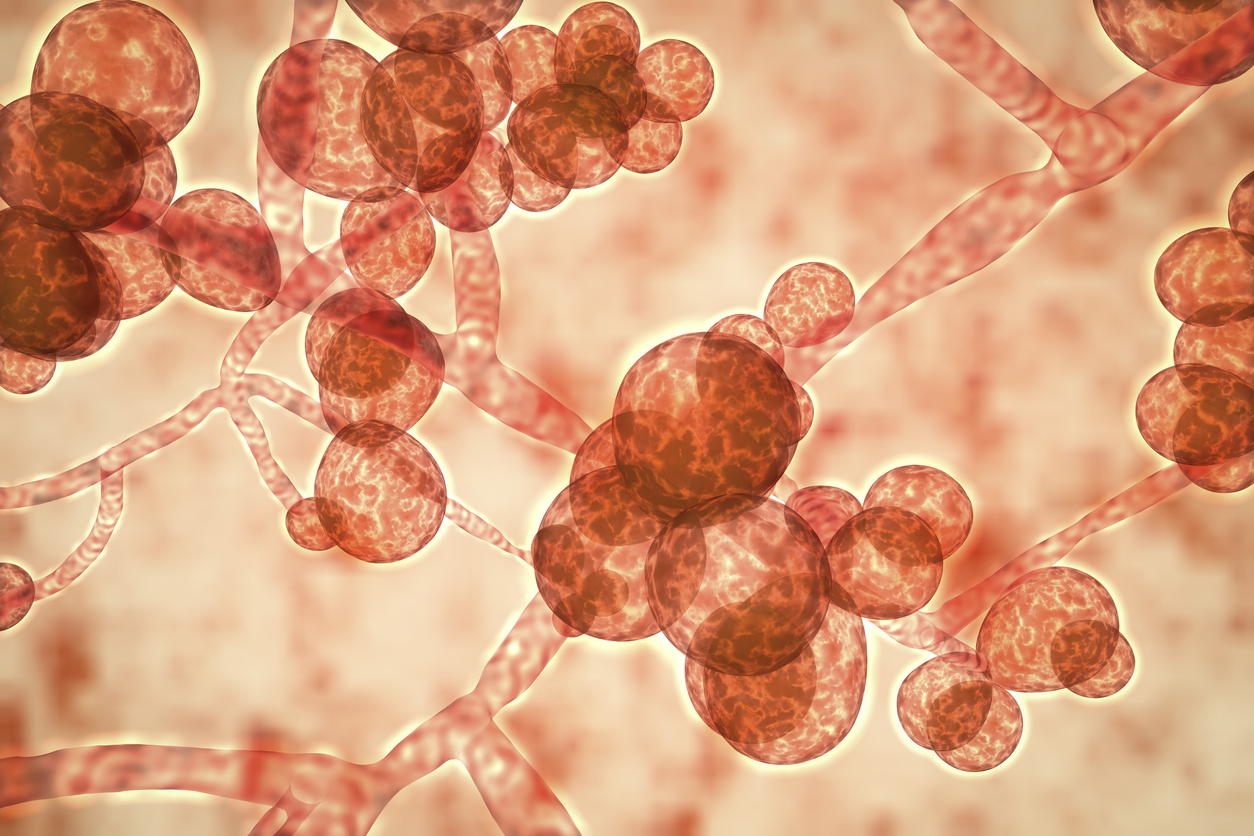

There were alarming headlines from the US over the weekend about a type of yeast that has been causing serious illness in hospital patients.

Candida auris can cause invasive infections and often does not respond to commonly-used antifungal drugs, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The SMC asked experts about the fungi and New Zealand’s preparedness.

Professor Michael Baker, Professor of Public Health, University of Otago, Wellington, comments:

“Reports about the rise of Candida auris are worrying as this organism is frequently resistant to multiple antifungal drugs. One unusual aspect of this pathogen is that it is a fungus, whereas most of the concerns about growing antimicrobial resistance (AMR) have been about bacteria. Since it was first detected and named in 2009 this organism has spread globally. A small number of cases have been detected in Australia, largely in people who have arrived from overseas. There do not appear to have been any reported cases in New Zealand to date, but it is almost inevitable that it will be seen here.

“Candida auris infections mainly occur in health care facilities (nosocomial infections) where they may cause prolonged outbreaks. It adds to the growing number of nosocomial infections that worsen outcomes for seriously ill patients, increasing mortality and the length of hospital stays. Control measures are broadly similar to those used for other resistant organisms in such settings, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

“New Zealand microbiologists and infectious disease specialists are aware of this organism and how to diagnose, treat and control it. However, it will inevitably add to the complexity and costs of managing nosocomial infections. New Zealand is very unlikely to experience the kind of secrecy described in the New York Times articlewhere there were apparently delays in reporting such infections to protect the commercial interests of some hospitals.

“The rise of Candida auris illustrates what AMR looks like. It will probably not be a single catastrophic event like a pandemic, but more a series of reminders that we cannot rely on antimicrobial drugs to work in the same way as they have in the past. In most cases, these infections will be a particular threat to the most vulnerable, such as those will underlying illness, immune-suppressive treatment, and the very young and elderly.

“Given the inevitability of increasing AMR threats, it is important to keep asking whether New Zealand is well prepared. Are our diagnostic and surveillance capabilities and response systems sufficiently developed and organised to respond in a highly coordinated way? Hopefully, this is one of the issues that the current Health and Disability System Review can consider.”

No conflict of interest.

Dr Heather Hendrickson, senior lecturer in molecular biosciences, Massey University, comments:

“Essentially, Candida auris is a yeast, not a bacterium. It has cells that are structurally more like ours (have a nucleus and mitochondria).

“It is frightening to read about because, like other superbugs, it is becoming increasingly resistant to the antimicrobials that doctors use to treat it and it is easily spread. This is also an emerging infectious organism that was first recognised in Japan in 2009 and appears to be springing up in many places around the globe simultaneously, but the isolates found in different locations are generally closely related to one another. This suggests that something environmental may be stimulating the transition of these to become serious threats in hospitals and in human patients, where they were not found previous to 2009.

“Importantly for the public in New Zealand, this is not on the list of notifiable infectious diseases here. This means that it is not publicly reported to the Medical Officer of Health if it is recognised in a hospital or lab.

“I am not aware of any reason that people in New Zealand should be overly concerned at this time. However, this is a good time to take a look at our monitoring practices and ensure that we are using the molecular tests that would allow us to identify this organism if it appeared clinically in our hospitals. Rapidly and accurately distinguishing C. auris from other infectious fungal pathogens is an important part of handling an infectious microorganism like this one.”

No conflict of interest.

Dr Matthew Blakiston, Clinical Microbiologist, Auckland District Health Board, comments:

“Candida are a group of fungal microorganisms. Most people carry common species like Candida albicans in their gastrointestinal tract. They frequently cause non-invasive mucosal infections such as oral and genital thrush. In hospitalised persons with severe underlying illness, Candida also cause invasive disease such as bloodstream infection.

“Candida auris is an antimicrobial-resistant species of Candida that has emerged over the past decade as a hospital-associated human pathogen. Like other hospital-associated invasive Candida infections, Candida auris infections primarily occur in critically ill persons in intensive care units. Despite some similarities with other species, Candida auris is also a novel pathogen in many ways. Firstly, as a fungus, it is unique among the emerging antimicrobial-resistant microorganisms; which are typically bacteria. Secondly, at least four different strains of Candida auris appear to have emerged independently of each other at different locations worldwide; suggesting common drivers in these geographically distant locations. Thirdly, it has a high propensity to spread from person to person in hospitals and cause difficult to control outbreaks; traditionally Candida has not been considered a transmissible infection in the healthcare environment, with infections developing from a person’s own endogenous flora. Last by not least, it is more resistant to treatment with antifungal agents compared with other Candida; potentially complicating and compromising treatment.

“The reason for the recent emergence of Candida auris is not clear; selective pressure from increasing use of antifungals in human health and agriculture is hypothesised as a cause. Its emergence has however not occurred in isolation but on a background of other developments in antimicrobial resistance among fungi globally. For instance, Candida albicans (a susceptible species) has historically been the most common cause of Candida infection. However, in a number of locations increasing numbers of infections with more resistant non-albicans species such as Candida galbrata are being seen. Increasing use of antifungals in human health is believed to be driving this change. Furthermore, in some European countries, antifungal use in agriculture is believed to be driving the emergence of antifungal resistance in the environmental fungal species Aspergillus fumigatus; this is an opportunistic mould that can cause severe infections in highly immunocompromised persons.

“Candida auris has not been described in New Zealand hospitals to date. However, as has occurred with other multi-drug resistant microorganisms, it is probably a matter of time. Similar to other emerging multi-drug resistant microorganisms, carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae for instance, recent hospitalisation in an endemic area would appear to be the greatest risk factor for C. auris infection in persons in the New Zealand healthcare environment. Early identification and the implementation of infection prevention and control measures, as currently utilised for other multi-drug resistant pathogens, are recommended to contain hospital spread.”

No conflicts of interest.