Last week, Associate Professor Euan Mason, of the School of Forestry at the University of Canterbury, commented on the likely effects on forestry and greenhouse gas production of the new, revised ETS announced then.

Last week, Associate Professor Euan Mason, of the School of Forestry at the University of Canterbury, commented on the likely effects on forestry and greenhouse gas production of the new, revised ETS announced then.

He has since received much interesting feedback on his statement, and as a result has reissued it, having amended and extended some of the comments.

Introduction

Following a review of the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) legislation, the New Zealand Government proposed to amend the legislation in the following ways:

- Agriculture, which is responsible for approximately half of our Nation’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, will not have to comply with the legislation until 2015, at which point it will receive free credits for 90% of its emissions. The amount of free credits received will subsequently decline at a rate of 1.3% per annum.

- The energy sectors will have to comply with the legislation from the middle of 2010, but will receive free credits for 95% of their emissions, dropping to 90% in 2013, and then the free credit allocation will decline at a rate of 1.3% per year.

- All allocations of free credits will be recalculated each year on the basis of levels of emissions at the time rather than those in 2005.

- The value of New Zealand Carbon Units (NZUs) will be capped at $25/unit.

These changes will strongly influence domestic demand for NZUs. The purpose of this note is to clarify, to the extent that is possible, the likely impacts of these changes on the forestry sector and most crucially on rates of new planting, which our previous commentaries have shown to be crucial so that we can avoid a large deficit in our national carbon accounts in the 2020s when current Kyoto-compliant plantations (those established on grassland after 1989) are likely to be harvested.

Impacts on domestic demand for NZUs

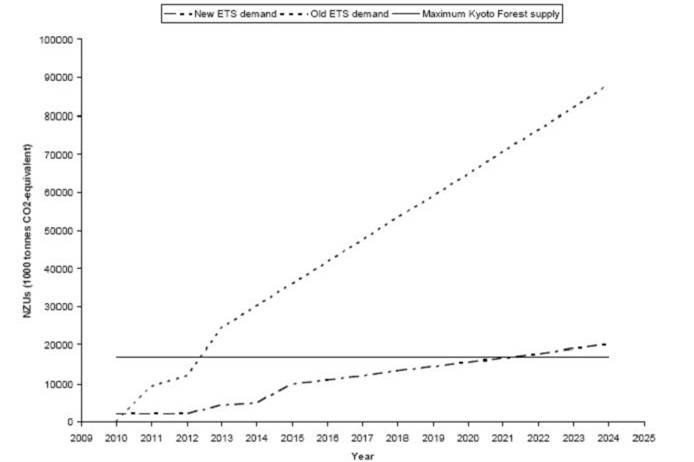

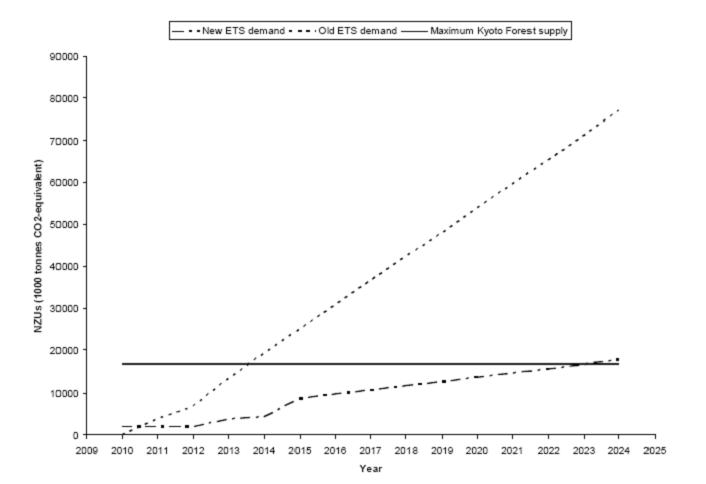

Under the existing ETS, domestic demand for NZUs would likely have exceeded the maximum capacity of existing Kyoto forest (planted since 1989 on grassland) to supply NZUs by approximately 2013, thereby providing a powerful incentive for investing in new forest plantings. A rough calculation suggests that if all current Kyoto forest owners registered for the scheme, then they could supply approximately 16,000,000 NZUs/annum, with this amount declining slowly until time of harvest.

Under the proposed ETS, domestic demand for credits would not be likely to exceed the maximum capacity of current Kyoto forest to supply NZUs until the early 2020s (Figure 1).

In making these calculations, there is a large uncertainty about national emissions of GHGs in future. The analysis assumes that the nation emits approximately 88 Mt of CO2 equivalent/annum (a 15% increase over current emissions), and 88 million NZUs are required to fully offset this level of emissions. National GHG emissions are likely to increase under the proposed ETS, which would bring forward the time when demand exceeded supply from existing forests, but this effect is difficult to quantify. If we assume that emissions stay at 2007 levels, then the likely level of demand is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1 – Assuming all current post-1989 forests registered for the ETS, that they all measured their C sequestration with high precision, and that New Zealand’s C emissions were at 15% above 2007 levels, the graph shows rough estimates of NZU demand from the old ETS, demand from the proposed ETS, and maximum possible supply from existing forests planted since 1989.

Impacts on supply of NZUs from the forestry sector

Supply of NZUs might come from three sources within the forestry sector. Firstly, a proportion of Kyoto forest owners will register for the ETS and the maximum possible supply from this source is approximately 16 million NZUs/annum. Secondly, pre-1990 forest owners will receive an allocation of 50 NZUs per hectare in compensation for the removal of the right to change land use without financial penalties. This latter supply of NZUs will be a one-off total of approximately 72 million NZUs. Perceptions of likely demand for NZUs and the extent to which this demand will be satisfied by NZUs accrued by existing forest owners will strongly influence levels of new planting, the third source of credits from the sector.

Figure 2 – Assuming emissions stay at 2007 levels, then the demand for credits would be somewhat reduced.

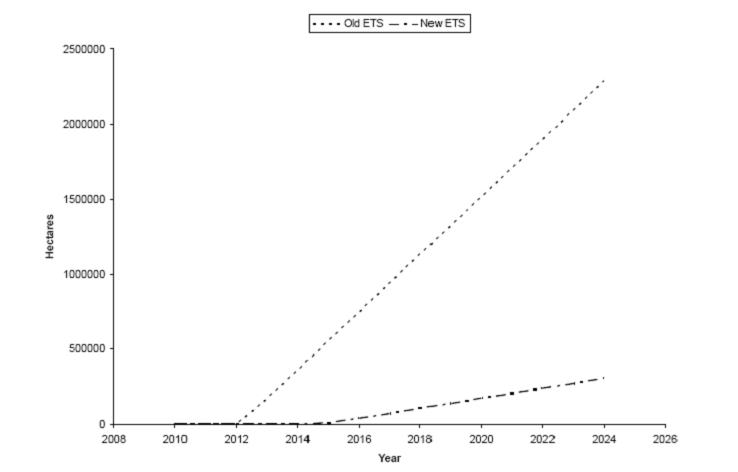

There is considerable uncertainty around how much of the potential NZU supply will be available in the domestic market, because not all Kyoto forest owners will register for the scheme, and many owners of NZUs may decide either to retain them or to sell them on the international market. This latter option is limited by Kyoto treaty rules to approximately 28 million credits during the first Kyoto commitment period. In addition, growers are credited with NZUs accrued up to the lower bound of the 90% confidence limit of the estimate of the difference between estimates of forest carbon at the beginning of a commitment period and estimates of forest C at the end. This means that high quality forest inventories are required in order for growers to claim the full value of C accrued by their forests. Realistically supply from current Kyoto forests might be between 50 and 75% of the maximum possible, which would lead to more incentive for new planting than if all NZU’s from existing forests were claimed and traded. Assuming forests were able to supply 30 NZUs/ha/year, Figure 3 shows the area of new forest required to meet domestic NZU demand for the existing ETS and the revised ETS under these circumstances.

Investments in new planting are typically very sensitive to land cost, and lower requirements for offsetting emissions (due to greater allocations of free credits to emitters) in the proposed ETS will very likely mean that land costs are higher than they would have been under the existing scheme. This will impact on planting rates, but the effect is difficult to quantify without a much more detailed analysis.

Figure 3 – Assuming that only 50% of the potential maximum NZUs from existing post-1989 forest are realised on the domestic market, and that new forests can supply 30 NZUs/ha/year, the graph shows the likely area of new forest required to satisfy the domestic market. Further assumptions for this graph include that emissions stay at 2007 levels, and that no harvesting occurs in existing post-1989 forest (this might lead to an increase in credit demand during the 2020s).

Final comment

In summary, the proposed ETS provides a weaker incentive for new forest planting than the existing ETS, and rough calculations suggest that all the domestic demand for NZUs could initially be met by sequestration in existing forests and from NZUs supplied to pre-1990 forest owners. The lower rate of reduction in free NZUs (1.3% per year) for emitters will mean that land values may remain higher and that there will be a significantly lower domestic demand for NZUs. On balance, the proposed ETS will require a slower rate of change in our behaviour with respect to GHGs.